Introduction

Central line–associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) are one of the costliest healthcare-associated infections in the United States in terms of patient mortality and value-based reimbursements. Most cases are preventable with proper aseptic techniques, surveillance, and preventative care management strategies. The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and the subsequent increase in CLABSI has further necessitated vigilance with CLABSI prevention measures.

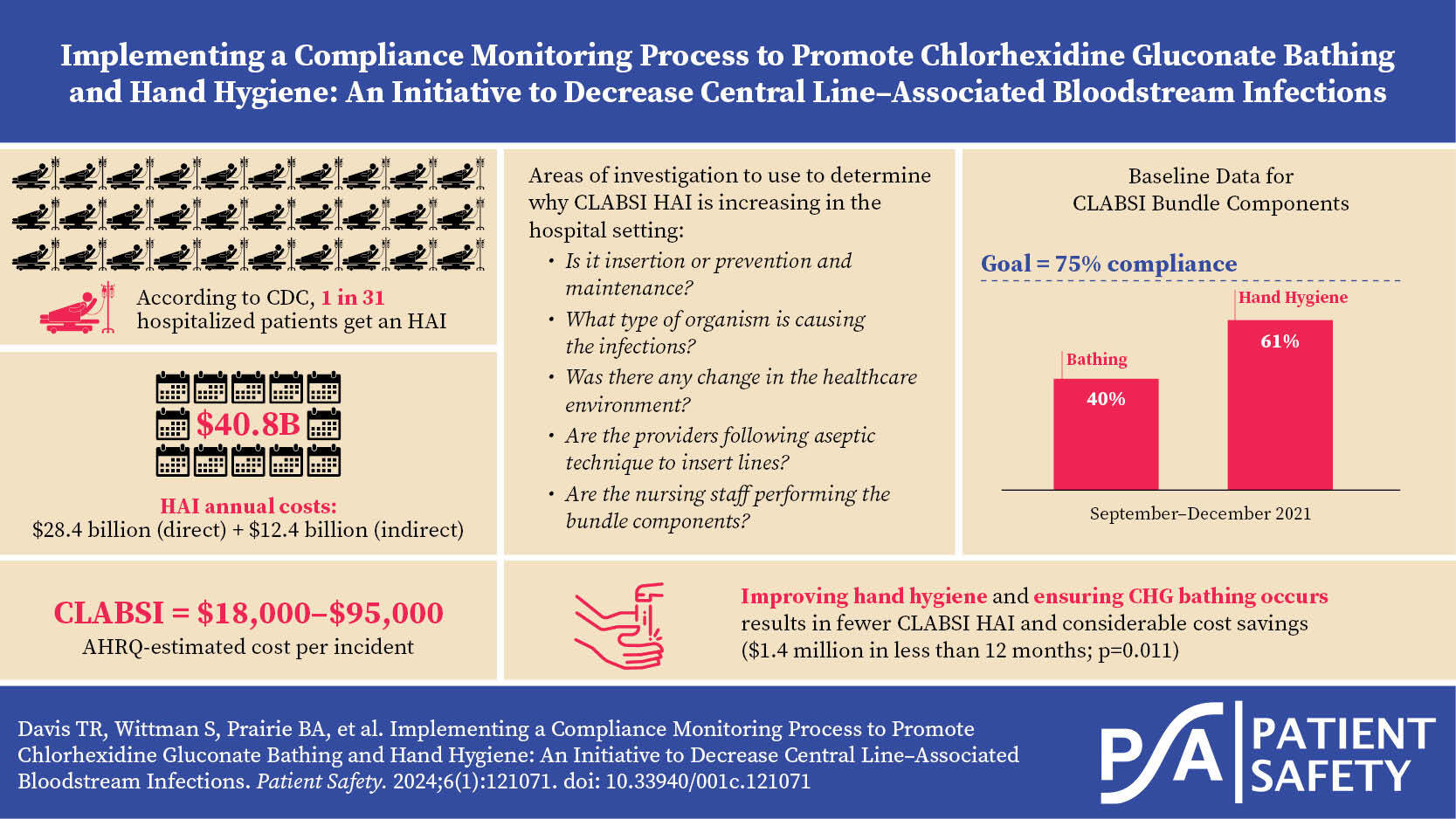

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 31 hospitalized patients will get an HAI.1 HAIs account for $34–74 billion annually in direct costs and $62–73 billion in indirect costs.2 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) estimates the cost of each incidence of CLABSI at $17,896–$94,879.3 In a 361-bed urban teaching hospital in Western Pennsylvania, CLABSI was a growing problem, particularly within the high-risk hematology/oncology patient population, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

From 2019 to 2021, the organization’s annual CLABSI count increased from 23 to 33, and the corresponding standardized infection ratio (SIR) increased from 1.04 to 1.49. In comparison, the SIR across general acute care hospitals was 0.92.4 Nationwide studies have shown a correlation between increased CLABSIs during the pandemic, with causative factors to include increased volume of high-acuity patients, staffing shortages, reduction in patient contact due to COVID-19 isolation practices, and overall reduction on preventive maintenance tactics.5–7

Objectives:

-

To evaluate the effectiveness of implementing a new compliance monitoring process to ensure strict chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) bathing and hand hygiene consistency and accountability as part of the CLABSI prevention bundle, in order to reduce overall CLABSI HAIs and SIR.

-

To evaluate if CLABSI HAI occurrence would be reduced in intensive care units (ICU) and non-ICU units.

-

To show the efficacy and cost benefit attributable to the increased compliance with CHG bathing for CLABSI HAI reduction on units with high incidence of CLABSI.

Review of the Literature

A review of the literature was performed utilizing the databases CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PubMed, JSTOR, and DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) for the keywords “central line-associated bloodstream infection prevention,” “CLABSI,” “chlorhexidine gluconate bathing,” “CHG,” “bloodstream infection prevention,” and “BSI.” Best practice standards for CLABSI prevention worldwide include aseptic insertion, proper site selection, hand hygiene, daily necessity assessment, aseptic dressing change, and integrity standards.8–11 In more recent studies the use of devices or dressings that include CHG has shown to reduce the risk of CLABSI, particularly in the ICU setting.12–14

Following the theme of CHG use, multiple studies show that the implementation of CHG-impregnated wipes or utilization of 4% CHG bathing solution has shown to reduce the risk of infection with common bacterial organisms causing CLABSI: E. coli, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterococcus spp. and decrease CLABSI and other HAIs.15–17 With the reduction of the potential pathogenic organisms on the skin, the overall incidence of CLABSI in hospitalized patients reduces, with or without a reduction in line days.18,19 In addition to the reduction of CLABSI occurrence, the cost savings incurred with the implementation of CHG bathing as a prevention tactic are significant.20,21

Methods

Study Design and Specific Aims

As a foundational step of this project, a CLABSI task force was formed to analyze the components of the organization’s CLABSI prevention bundle and to find the root causes: insertion, care and maintenance, or both. The group was made up of the chief medical officer as the executive sponsor; the quality director and nursing quality manager as the facilitators, the infection prevention team as the presenters and scribes; the vascular access team (VAT) as the process checkers, and nursing and physician representatives from targeted nursing units included in the study. The group analyzed data trends: unit occurrence, organisms, days from central line insertion to infection, CLABSI root cause analysis (RCA) results, and direct observation compliance with other elements of the CLABSI bundle. Analysis revealed causation to be associated with the care and maintenance phase of CLABSI prevention, with CHG bathing and hand hygiene compliance as the two components with lowest consistency and compliance. See Table 1.

The group used The Joint Commissions Robust Process Improvement framework to conduct a quasi-experimental study on the effects of a compliance monitoring process for CHG bathing and strict hand hygiene within ICU and non-ICU inpatient hospital units in an urban 361-bed teaching hospital in Western Pennsylvania. The pre-intervention period consisted of January through August 2021. In the month preceding the intervention time period, the nursing units received added education on the Biopatch CHG dressing and multimodal education offerings for CHG bathing.

The overall hospital CLABSI goal was to decrease the annual infection count from 33 to 29, and to decrease CLABSI SIR from 1.49 to 1.33. Within the CLABSI performance improvement nursing units, a universal SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound) goal process and framework was used:

In order to increase compliance with CLABSI prevention interventions, X unit will implement audits to validate completion of the following: Bedside Shift Report (BSR) checklist, hand hygiene audits with a compliance goal of >75%, CHG bathing, and existing CLABSI bundle components performed 3 times per week by charge nurse (if unableàAssistant Nurse ManageràNurse Managerà CTF member) unit starting Sep 1, 2021, with goal of X infections annually or a rate of X per month until Nov 30, 2021. Interventions will continue on unit until 3-month steady state achieved, at which time the VAT or Shared Governance Council will randomly audit monthly. If at any time the unit exceeds monthly goal rate or annual goal, the unit will restart interventions.

The SMART goal process and framework was utilized to establish CLABSI reduction goals for each unit that were realistic and achievable. These goals were created taking into consideration historical data as well as patient population. The CLABSI process improvement nursing unit goals were approved by nursing and hospital leadership. The aim of the study was to determine if the implementation of a compliance monitoring process for CHG bathing and strict hand hygiene, in addition to the traditional CLABSI prevention bundle, will reduce the overall hospital CLABSI SIR.

Intervention

The intervention period consisted of September to November 2021, with post-intervention and sustainability analysis between December 2021 and June 2022. Reinforcement of daily CHG bathing and adherence to hand hygiene practices were reestablished as critical components of the CLABSI prevention bundle. The test of change was implemented without change to the standard CLABSI prevention bundle (which includes standardized insertion checklists and processes, daily necessity assessment, dressing change and integrity standards, five moments hand hygiene standards, CHG disk [Biopatch], end caps [Curos], and care of tubing).

Hospital HAI surveillance was completed by the infection preventionists, utilizing the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) definitions.22 Direct observations of daily CHG bathing and documentation compliance occurred by the Nursing Unit leadership and staff each week starting September 1, 2021. They provided additional details on direct observation audits with immediate feedback and monthly surveillance reports to leadership at the unit and individual staff level using the Ecolab compliance monitoring system.

As part of interrater reliability and to ensure other elements of the CLABSI bundle did not incur slippage, the VAT conducted observations on the targeted units of CHG bathing as well as the other bundle elements (dressing integrity, CHG disc, line care, end caps, etc.). Observation data was recorded on an online platform to minimize paper submission process, allow real-time review, and enhance the data analysis process.

Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 28 and statistical process control charts were used to decide the statistical significance of outcomes. Pre-intervention and post-intervention outcome data including CLABSI HAI occurrence and rate, as well as hospitalwide SIR, were evaluated for statistically significant improvement. Significance level p<0.05 was assigned to the performance improvement project. Continuous variables were analyzed by comparing means of pre- and post-intervention data using independent t-tests.

Results

During the quasi-experimental study, a statistically significant increase in hand hygiene (p=<0.001) and a statistically significant increase in CHG bathing compliance (p=0.014) in the ICU helped reduce the overall hospital CLABSI SIR from 1.45 to 0.82, representing an overall 43.4% decrease (Table 3 and Figure 1). The non-ICU units, which consisted of a stepdown unit and bone marrow transplant unit with a large volume of central line days, decreased CLABSI HAI by 10.2%, but this was not statistically significant (p=0.814). Of note, CLABSI SIR at the unit level could not be calculated due to volume requirements to generate an SIR.

Due to small volume, CLABSI HAI rate per 1,000 central line device days was compared pre- and post-intervention, and though both rates decreased in the ICU and non-ICU units, neither was statistically significant. The ICU had a CLABSI HAI rate per central line device day reduction of 43.2% and non-ICU units had a 12.2% reduction in CLABSI HAI rate per central line device day. Cost reduction was statistically significant (p=0.011) and was an estimated 1.4 million dollars in savings for the hospital (Table 3). Further study with a larger sample size and evaluation of the causative organism may be needed for hospitals with large hematology oncology patient populations with multidrug-resistant organisms (MDRO) for CLABSI prevention.

Evaluating the pre- and post-intervention periods, central line days increased in both the ICU and statistically significantly in the non-ICU units (p=0.025) (Table 3 and Figure 2). Bathing adherence on the intervention units increased from baseline of 43% to 62% and stood for an overall increase of 44%, with statistical significance in the ICU (p=0.14) but no statistical significance in the non-ICU units (p=0.690) (Table 3). Hand hygiene compliance within the intervention units increased from baseline 61% to 81%, being a 33% increase. Anecdotally, use and compliance of travel or agency nurses was not within the scope of this project, but may warrant future examination.

The quasi-experimental study had several limitations. The performance improvement project was a single center study conducted over a 10-month period of time. The study did not evaluate any correlation between CHG bathing and hand hygiene compliance with patient clinical characteristics, causative organisms, central line type, or staffing (employed vs contracted staff, licensed vs unlicensed staff). The Hawthorne effect, which states that staff knowing they are being studied may impact their behavior, may have had an initial positive impact on the decrease in the CLABSI SIR, as noted in the decrease in CLABSI SIR when the CLABSI task force was formed in September (Figure 1).22 The formation of the task force and its focus was well-known within the hospital and on the targeted units. In addition, the unit-specific observations for CHG bathing and hand hygiene were primarily conducted by staff within those departments.

Another limitation of the study revolved around the recent implementation of electronic technology for hand hygiene compliance. Numerous operational issues related to functionality of badges, wearing of badges, and compliance zones continue to be refined. Additionally, validation of compliance specific to observation of bathing vs compliance of documentation in the electronic medical record was a limitation. During the observation period, discussion occurred about how to improve patient education and messaging to patients about the importance of CHG bathing as a “treatment” or part of the care bundle vs a bath; this was not included in this study. Staffing was another limitation of this study; staffing variables such as employed vs contracted staff, licensed vs unlicensed assistive personnel, staffing ratios, and turnover were outside of the scope of this project. Continued study on limitations and the sustainability of the project is needed.

Discussion

Ensuring compliance with 4% CHG bathing and strict hand hygiene in standard nursing care within high-risk nursing populations, such as critical care, hematology oncology, and patients with invasive devices, will result in an overall hospital reduction in HAI CLABSI and a corresponding reduction in overall hospital unnecessary expenditures. Ongoing study on the efficacy and sustainability of CHG bathing compliance and consideration for the staffing mix and use of agency/travelers within the nursing unit are needed in the post COVID-19 pandemic healthcare setting. Next steps include a multicenter trial to adequately evaluate sustainability of the CHG bathing compliance monitoring process.

Acknowledgement

The completion of this performance improvement project would not have been possible without the assistance of the nursing and quality staff’s contribution to data collection audits. We would like to thank Jacqueline Drahos, Allison Kelly, Mona Dubaich, Kari Smith, Anna Marie Pozycki, Charles Herman, Christine Fabrizio, and Kathryn Straatmann.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

About the Authors

Tanisha Davis (tanisha.davis@ahn.org) is a registered nurse and U.S. Navy veteran with over 25 years of healthcare experience and has specialized as a quality improvement leader for the last 11 years. She completed her baccalaureate at Florida State University, her master’s degree at University of Pittsburgh, and doctor of nursing practice at Capella University.

Susanne Wittmann received her Bachelor of Science in nursing from the University of Pittsburgh and a Master of Science in health service administration from the University of St. Francis in Joliet, Illinois. She has over 30 years of nursing experience in a variety of roles, including patient care, management, education, and quality in a four-time Magnet-recognized acute care hospital.

Beth A. Prairie is board certified in both obstetrics and gynecology and preventive medicine. Dr. Prairie has more than 15 years of experience working in process improvement in hospitals and public health departments. Currently, she serves as the chief medical officer for West Penn Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Dr. Prairie completed her medical degree at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine and her residency training with a Master of Public Health at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire.

Nancy Dugan, a registered nurse and infection preventionist, has 23 years of experience in both acute care and critical care settings. She holds a Certificate of Infection Control from the Certification Board of Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc. She completed her Bachelor of Science from the University of Pittsburgh and Master of Science from Carlow University.

Patricia Reiser completed her Bachelor of Science in nursing through Capella University. She has over 40 years of nursing experience, primarily in oncology nursing in both the inpatient and outpatient setting. In addition, she has completed vascular access training and education through the Infusion Nurses Society and Association for Vascular Access over 25 years ago.

Leah Goclano is a microbiologist and infection preventionist with over 13 years of experience. She completed both her Bachelor of Science in microbiology and her Master of Health Administration from the University of Pittsburgh.

Rose Dziobak graduated from West Penn Hospital School of Nursing in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She has 44 years of nursing experience, 22 of which have been with the vascular access team. Over the years, she has seen how a CLABSI can negatively impact patients and their recovery.