Introduction

Medication errors represent a significant challenge to patient safety. They have been suggested as the most common type of preventable error,1,2 with hospitalized patients potentially experiencing at least one medication error every day.3 The magnitude and severity of this problem is reflected in data from the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting System (PA-PSRS)[1], which received 40,680 reports of medication errors in 2023 alone, 294 of which reporters classified as a serious event that resulted in patient injury or death.4,5

Among these medication errors are wrong drug events (WDEs), which occur when a patient receives a medication different from the one intended. The case of RaDonda Vaught serves as a reminder of the potentially fatal consequences of WDEs, especially when they involve high-alert medications.6 In this instance, the accidental administration of vecuronium, a paralytic agent, instead of the intended sedative, midazolam, resulted in the patient’s death.7 Vecuronium was accidentally dispensed after “VE” was typed into the automated dispensing cabinet (ADC) in an attempt to locate “Versed,” a discontinued brand name of midazolam.7

Previous literature has identified numerous factors contributing to WDEs, including similarities in names, packaging, and tablet/capsule appearance, as well as human factors such as limited knowledge, inattention, haste, communication failure, and fatigue.8–18 A major focus within this body of research has been placed on the issue of confused medication names,9–16 which are medications with similarities in phonology (the spoken forms) or orthography (the written forms) in generic names, brand names, abbreviations, or any combination thereof.9–11 Often referred to as “look-alike, sound-alike” medications, these can lead to errors throughout all stages of the medication-use process.10,11

In this study, we examine the current state of WDEs through an analysis of patient safety event reports. Based on reports submitted to PA-PSRS in 2023, we identify the specific medications most frequently involved in WDEs and summarize events resulting in patient harm. By understanding the medications involved in WDEs, healthcare facilities can prioritize focused internal reviews, development of proactive risk assessments, and strategies to minimize the occurrence of WDEs.

Methods

We used data from PA-PSRS, a repository containing over 5 million event reports from healthcare facilities across Pennsylvania.19

We queried PA-PSRS for reports submitted between January 1, 2023, and December 31, 2023, under the “Wrong Drug” subtype of the “Medication Error” event type category with a harm score of C or higher to focus on events that reached the patient.5 Each report was then manually reviewed and the following inclusion criteria were applied:

-

The report described a WDE, which we defined as “an event in which one medication was inadvertently ordered, dispensed, or administered in place of another medication that contained a different active ingredient.”

-

The report identified the names of both medications involved.

-

Both medications involved in the event are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).20,21

Reports were excluded if they described the following:

-

Two medications that share the same active ingredient(s) but differ in dose, concentration, rate of administration, route (e.g., bisacodyl enema and suppository), or formulation (e.g., bupropion immediate release and sustained release).

-

Two vaccines that treat the same organism(s) but differ in antigen serotype or intended age group (e.g., Menveo and Bexsero, Tdap and DTaP).

-

Both medications involved in the event were maintenance intravenous (IV) fluids, irrigation fluids, or dialysates. (The following hypertonic solutions were not excluded, as they are considered high-alert medications:6 sodium chloride with a concentration greater than 0.9% and dextrose with a concentration of 20% or greater).

Coding and Data Analysis

We reviewed and analyzed structured variables that are coded by the reporter at the time of submission, including facility type, care area[2], event classification (incident[3] or serious event[4]), and details related to the medication prescribed and medication administered, such as medication name, dose, and route. The pharmacist researcher manually reviewed and standardized the medications to generic names for consistency, while also maintaining the brand name(s), and acknowledged medication pairs in cases where the medications had phonetic or orthographic similarities and/or the confused medication names were reported as a contributing factor to the WDE. The researcher also categorized the medications by applying the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system by the World Health Organization (WHO).22 Similarly, high-alert medications were initially coded by the reporter during submission; however, to ensure accuracy and consistency, the researcher made adjustments as needed based on the Institute for Safe Medication Practice (ISMP) List of High-Alert Medications.6 To gather additional contextual information about the WDEs, the researcher also reviewed the unstructured free-text data fields of the PA-PSRS reports, primarily focusing on the Event Description.

We performed a descriptive analysis to summarize and describe the data in a meaningful way and to identify any previously undocumented phenomena or patterns within the literature.23 A variety of techniques, including frequency tables, cross tabulations, and bar charts, were used to provide a high-level overview of the data.

Results

Healthcare Facility Demographics

Our query of the “Wrong Drug” subtype in PA-PSRS produced 1,192 reports, 450 of which met criteria for inclusion in the study. These events occurred across 127 different healthcare facilities, representing 10 distinct facility types as shown in Figure 1. More than half of the events (56.4%, 254 of 450) were associated with four care area groups: medical/surgical unit (19.6%, 88 of 450), intensive care unit (12.7%, 57 of 450), emergency department (12.4%, 56 of 450), and surgical services (11.8%, 53 of 450).

Medication Classes, Individual Medications, and Pairs Involved in WDEs

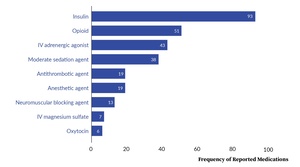

Figure 2 shows the most frequently reported medication classes based on ATC categorization.22 Insulin was reported most frequently, comprising more than one-tenth (10.3%; 93 of 900) of all reported medications. Other medication classes that were frequently reported include antibacterial for systemic use, electrolyte solution, opioid, and cardiac stimulant.

Table 1 shows the most frequently reported individual medications involved in WDEs and the medications with which they were erroneously interchanged most frequently.

The medication pairs listed in Table 1 demonstrate that WDEs frequently occur within the same class. For example, insulins were commonly confused with other forms of insulin. Similarly, epinephrine and norepinephrine were mistaken for one another, and hydromorphone was interchanged with other opioid medications. This pattern was also evident with antibiotics, as cefazolin was often confused with other antibiotics, particularly those within the same cephalosporin subclass.

While many of the medications in Table 1 involve confusion within the same medication class, some exceptions exist. For example, normal saline solution (NSS) and heparin were confused with a wide range of medications across numerous classes. In contrast, hydroxyzine demonstrated a different pattern of confusion, being mistaken for hydralazine and hydrochlorothiazide (HCT or HCTZ), as an example of confused medication names contributing to WDEs.

Table 2 provides a list of the most frequent medication pairs involved in WDEs, all of which follow the pattern of belonging to the same class and/or having similar phonetic and/or orthographic features in their generic or brand names. This similarity is often evident in shared stems within a drug class, such as “cef” for cephalosporin antibiotics or “phrine” for vasopressors (e.g., epinephrine and norepinephrine). Additionally, confusion can arise from similar brand names, such as Solu-Cortef (hydrocortisone) and Solu-Medrol (methylprednisolone succinate), or within various insulin types (e.g., Humalog and Humulin).

Furthermore, Table 2 includes combination products that contain two active ingredients. Medications with two active ingredients can be confused with a single-entity medication containing only one of two active ingredients (e.g., oxycodone and oxycodone/acetaminophen, ampicillin and ampicillin/sulbactam). While not shown in Table 2, this issue extends to other medication pairs such as albuterol and albuterol/ipratropium and amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate, which were also identified in the analysis.

Table 3 lists additional medication pairs that share similar names but were reported less frequently than those identified in Table 2.

High-Alert Medications

Our analysis revealed the involvement of 312 high-alert medications across 197 event reports. More than half of the reports (57.4%, 113 of 197) involved confusion between two high-alert medications. Figure 3[5], which displays the most frequently reported classes of high-alert medications, shows that insulin comprised 29.8% (93 of 312) of all reported high-alert medications.

Of the 13 neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBs) that were identified across 11 event reports, seven were rocuronium, four were succinylcholine, and two were vecuronium. As a result of these 11 events, five patients did not achieve necessary muscle paralysis, four patients received unnecessary paralysis, and two patients received incorrect NMBs.

Intravenous oxytocin, which comprises its own high-alert medication class, was reported in six events. Four of these events occurred in the Labor & Delivery and Postpartum Recovery units and involved confusion with fluids or magnesium sulfate.

Furthermore, one of the events involving an antithrombotic agent described a WDE that resulted in accidental administration by the wrong route. Heparin, which was intended by the subcutaneous route, was administered IV due to confusion with IV famotidine.

We also identified WDEs involving high-alert medications and their reversal agents that led to an unintended therapeutic effect. For example, naloxone, an opioid antagonist, was administered in cases where fentanyl or hydromorphone were intended. In another case, succinylcholine, a depolarizing NMB, was administered instead of sugammadex, a reversal agent for non-depolarizing NMBs. Although the actual impact on patients was not described in these reports, we can theorize that the WDEs led to a delay, failure to produce the intended effect, or exacerbation of the adverse effect the providers were attempting to mitigate.

Serious Events

The majority of reports (97.3%, 438 of 450) were classified as incidents. Of the 12 reports that were classified as serious events, more than half (58.3%, 7 of 12) involved one or more high-alert medications. Insulin was involved in four of the serious events and an NMB was involved in two events. All of the serious events involving insulin described insulin that was unintentionally administered to a patient, which led to hypoglycemia and required immediate medical intervention.

Two of the serious events described carvedilol being inadvertently administered at high doses, leading to a decrease in blood pressure and requiring immediate medical intervention and an increased length of stay. Another serious event report described a patient who developed hemolytic anemia, requiring a blood transfusion and readmission to the hospital following accidental administration of an antibiotic to which the patient had a previously documented allergy.

Discussion

Impact of WDEs on Patients

The administration of incorrect medication and deviation from the intended treatment can impact patients in several different ways. The omission of a necessary dose intended to treat or manage a medical condition can have adverse effects. Patients may also experience adverse effects if given unnecessary medication due to a WDE. For example, our analysis revealed instances where NMBs were mistakenly administered to several patients. This is particularly concerning given NMBs’ ability to induce paralysis and potential to cause serious injuries or death when used in error.7,24

Moreover, the inadvertent administration of a medication presents additional risk because the medication is not evaluated against the patient’s medical history or allergies. Such was the case involving the administration of an antibiotic to a patient despite the patient’s documented allergy, which resulted in a reaction and readmission to the hospital.

An additional risk associated with WDEs is the potential for other medication errors, such as errors in dose, route, rate, and time. Two serious events in our study involved the incorrect administration of carvedilol to patients who had not previously received the medication. The recommended initial dose of carvedilol, depending on the indication, is 3.125 milligrams or 6.25 mg twice daily, with titrations to the desired maintenance dose occurring gradually over several days or weeks with careful monitoring for adverse effects.25 Consequently, unintentionally initiating treatment with an inappropriately high dose can result in serious patient harm, as seen in our analysis.

In the events involving the inappropriate administration of reversal agents, the administration of unintended medications not only delayed or failed to provide the intended therapeutic effect, but also potentially exacerbated the adverse effects that the providers attempted to mitigate.

WDEs and Medication Classes

By examining WDEs in the context of medication classes, our study builds on previous research that focused primarily on medication pairs.9–14 Our findings revealed a pattern of medication confusion within drug classes, with insulins, vasopressors, antibiotics, opioids, and benzodiazepines frequently being mistaken for similar medications within their respective groups. A plausible explanation for this phenomenon is the similarity in nomenclature within these classes, in which many medications share common stems26 that contribute to confusion. Additionally, medications within the same therapeutic class often share similar indications and are used to treat patients with comparable medical conditions.

A notable finding from our study is the high frequency in which insulin was involved in WDEs. The three most frequently reported individual medications in our analysis were all insulins (lispro, regular, and glargine). This observation contrasts with previous literature from approximately two decades ago, which identified opioids as among the most frequently reported,13,14 although it is important to acknowledge methodological differences between the studies.

Confused Medication Names

Naming conventions of medications face the challenge of balancing two competing goals: minimizing the risk of confusion and ensuring that names are readily identifiable and understood in relation to chemical composition, pharmacological action, and/or therapeutic use.10 While the use of similar names for medications within the same class can facilitate identification, it can also increase the risk of WDEs. For example, cephalosporin antibiotics are characterized by their shared “cef” stem; according to the FDA’s list of approved drugs as of January 2025,20 there are 17 commercially available cephalosporin antibiotics containing “cef” within their names. This pattern of similar nomenclature within subclasses extends to other antibiotic classes, including aminoglycosides (e.g., gentamicin, streptomycin, tobramycin), carbapenems (e.g., ertapenem, imipenem, meropenem), fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, ofloxacin), glycopeptides and lipoglycopeptides (e.g., dalbavancin, oritavancin, telavancin, vancomycin), macrolides (e.g., azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin), rifamycins (e.g., rifabutin, rifampin, rifaximin), and tetracyclines (e.g., doxycycline, minocycline, tetracycline), among others.27

In addition to shared stems, and other name components, certain medications within the same class may also be referred to by similar abbreviations. For example, alteplase and tenecteplase are sometimes abbreviated by “TPA” and “TNK,” respectively.28–30 Alteplase presents a unique case where “TPA” not only refers to the individual medication but also to the broader class of tissue plasminogen activators, to which both alteplase and tenecteplase belong.29–31 This overlap in abbreviation further contributes to the potential for confusion and medication errors.

Multiple organizations have endeavored to mitigate WDEs arising from medication name confusion. These efforts include the Phonetic and Orthographic Computer Analysis program by the FDA, which assesses the similarity of names based on a computer algorithm and assigns a percent similarity score to a given name pair.32 ISMP maintains the List of Confused Drug Names11 and the Lists of Look-Alike Drug Names With Recommended Tall Man (Mixed Case) Letters.33 However, it is crucial to acknowledge that these lists cannot encompass all possible medication combinations involved in WDEs, and confused medication names represent only one facet of a broader, complex issue.

Future Research

While we have identified key insights regarding the medications and medication pairs commonly involved in WDEs, additional investigation may provide a deeper understanding of the factors that contribute to these events. Such insights could enable further development and prioritization of targeted prevention strategies for WDEs.

Limitations

Several limitations inherent to this study warrant careful consideration when interpreting the findings. Despite Pennsylvania’s mandatory reporting laws, PA-PSRS data fundamentally reflect the complexities of staff-driven identification and reporting processes. Also, the reporter’s interpretation of an event can introduce bias in the classification of event types. For example, a WDE involving medication administration to the wrong patient may be reported under the “Wrong Patient” subtype rather than the “Wrong Drug” subtype. Since our study focused exclusively on reports categorized as “Wrong Drug” events, relevant WDEs classified under other Medication Error subtypes may have been inadvertently excluded.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the medications involved in WDEs and their impact on patients.

Conclusion

WDEs can cause serious patient harm resulting from the omission or delay of a necessary medication, administration of an unintended and/or contraindicated medication, or other deviation such as administration via the incorrect route due to confusion between two medications. Our findings highlight insulin as the medication class most frequently involved in WDEs. Additionally, our study underscores the need for heightened attention to medications with similar names, including those with shared stems. Additional research regarding the contributing factors to WDEs could provide a more complete understanding of these events and facilitate further development of evidence-based, targeted prevention strategies.

Note

This analysis was exempted from review by the Advarra Institutional Review Board.

Data used in this study cannot be made public due to their confidential nature, as outlined in the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error (MCARE) Act (Pennsylvania Act 13 of 2002).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

About the Authors

Myungsun (Sunny) Ro (mro@pa.gov) is a research scientist on the Data Science & Research team at the Patient Safety Authority (PSA). Her responsibilities include analyzing and synthesizing data from various sources to identify opportunities to improve patient safety, as well as writing scientific articles for publication in PSA’s peer-reviewed journal, Patient Safety.

Rebecca Jones is director of Data Science & Research at the Patient Safety Authority.

PA-PSRS is a secure, web-based system through which Pennsylvania hospitals, ambulatory surgical facilities, abortion facilities, and birthing centers submit reports of patient safety–related incidents and serious events in accordance with mandatory reporting laws outlined in the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error (MCARE) Act (Act 13 of 2002).4 All reports submitted through PA-PSRS are confidential and no information about individual facilities or providers is made public.

Within the PA-PSRS acute care database, there are 168 care areas for facilities to use to identify where events occur. Each of these care areas is then placed into one of 23 higher level care area groups.

An incident is defined as “[a]n event, occurrence or situation involving the clinical care of a patient in a medical facility which could have injured the patient but did not either cause an unanticipated injury or require the delivery of additional health care services to the patient.”4

A serious event is defined as “[a]n event, occurrence or situation involving the clinical care of a patient in a medical facility that results in death or compromises patient safety and results in an unanticipated injury requiring the delivery of additional health care services to the patient.”4

Due to the use of a different system to classify high-alert medications, the frequency of some high-alert medication classes shown in Figure 3 do not exactly match the classes shown in Figure 2. For example, there is a lower frequency for “Antithrombotic agent” in Figure 3 compared to Figure 2 because subcutaneous heparin is not considered a high-alert medication.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)