Introduction

Inpatient falls are a continuing patient safety issue nationwide.1–4 In Pennsylvania alone, 35,450 falls were reported to the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting System (PA-PSRS)[1] in 2024, with 3.2% classified as a serious event that resulted in either death or an unanticipated injury requiring the delivery of additional healthcare services.5 A breadth of previous work has investigated inpatient falls, leading to the development and implementation of numerous prevention strategies.6–9 For example, previous studies have found that universal fall precautions should be in place regardless of a patient’s fall risk to reduce the risk of falls.10 Implementing the use of personalized risk assessment and care plans,1,3,6–8,11 staff and patient education,7 and patient safety technology (e.g., bed and chair alarms)7,9 can also help with fall prevention. Falls after hospital discharge (e.g., those that occur within three months following discharge) have also been studied previously.12–17 Fall prevention strategies for the post-discharge destination15 are similar to those targeting prevention of inpatient falls and include hand-off communication,18 patient education,14,15,19 and environmental safety measures (e.g., clearing the floor of clutter).20

While inpatient falls and falls after the patient leaves hospital grounds are well researched, falls that occur during the time frame surrounding discharge have yet to be fully investigated in the literature. This transitional period may present a unique set of conditions that enhance patients’ perceived independence and inadvertently reduce vigilance toward fall prevention. Although medically stable for discharge, these patients may still be at risk of falling. Maintaining appropriate precautions throughout the discharge period is vital to patient safety. In this study, we aim to examine the characteristics, contextual factors, and impact of falls that occur during the period surrounding discharge, while the patient was still in the hospital or on hospital grounds, to better understand how the events affect patient safety.

Methods

We defined a fall surrounding discharge as any unintentional fall that occurred after the patient had been formally discharged (e.g., while waiting for transport or exiting the facility) or on the same day the patient was scheduled for discharge.

Data Query

Data for this study were collected from event reports in the PA-PSRS acute care database. PA-PSRS reports contain responses to structured fields (e.g., event date, event type, harm score, patient age, patient sex at birth) and free-text narrative fields that allow reporters to describe event details in their own words. We queried PA-PSRS for reports submitted between July 1, 2023, and June 30, 2024, under the event type Falls. To focus our analysis on inpatient hospital events, we limited the facility types to include only acute care hospitals and 10 care area groups[2] (intensive care unit, intermediate unit, medical-surgical unit, labor and delivery, obstetrics and gynecology unit, pediatric unit, pediatric intensive care unit, psychiatric unit, rehabilitation unit, and specialty unit). This initial search produced 25,954 reports.

To target falls surrounding discharge, we applied a search of the free-text fields for at least one of the following keywords potentially indicating the patient’s discharge status or intended post-discharge destination: “discharg,”[3] “d/c,” “DC,” “home,” “SNF,” and “skilled nursing.” This keyword search yielded 1,086 reports which were then manually reviewed to identify those that met our definition of a fall surrounding discharge. Reports that did not meet the definition remained in the group of reports identified through our initial search, which was used as a comparison group for statistical analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the stepwise process of identifying and refining the search for inpatient falls surrounding discharge. The comparison group was not analyzed beyond statistical comparison to the falls surrounding discharge group.

Variables Coded

We analyzed the falls surrounding discharge using data entered by the reporter in both structured and unstructured (free-text) fields of the reports. We analyzed patient demographics (age and sex) and event classification (incident and serious event), which are provided in the structured fields. The terms “incident” and “serious event” are defined in the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error (MCARE) Act (Act 13 of 2002)21 as follows:

-

Incident: “An event, occurrence, or situation involving the clinical care of a patient in a medical facility which could have injured the patient but did not either cause an unanticipated injury or require the delivery of additional healthcare services to the patient.”

-

Serious Event: “An event, occurrence, or situation involving the clinical care of a patient in a medical facility that results in death or compromises patient safety and results in an unanticipated injury requiring the delivery of additional healthcare services to the patient.”

Fall risk[4] and fall history[5] for each patient were coded using information from the structured fields, as well as details from the free-text fields. Additionally, the information in the free-text fields underwent a rigorous two-stage coding process. In the first stage, one researcher identified and coded the variables listed below. If a report lacked clarity or presented ambiguities, a second researcher reviewed the report and engaged in discussion until consensus was reached.

Fall Type. We analyzed the reports to identify the type of fall that occurred using the PA-PSRS Falls Event Type Decision Tree for Hospital Users.22 This decision tree was developed by the Patient Safety Authority to help facilities systematically evaluate patient falls and consistently identify specific fall event types. Additional relevant details for certain fall types were identified and coded, and these will be further explored in the Results.

The following fall types are specified in the Falls Event Type Decision Tree: lying in bed, assisted, sitting at side of bed, sitting in chair/wheelchair, transferring, ambulating, toileting, in the exam room/exam table, hallways of facility, grounds of facility, from stretcher, found on floor, and other[6].

Discharge Phase. We evaluated the reports to determine the patient’s phase of discharge at the time the fall occurred.

-

Discharge Complete: The report described a patient who had already been discharged at the time the fall occurred.

-

Discharge Pending: The report described a patient who was scheduled to be discharged on the same day the fall occurred.

Injury Type[7]. We reviewed the report details to identify the type of injury, if any, the patient sustained as a result of the fall.

-

No Injury: The event details explicitly indicated there was no injury to the patient.

-

Superficial Skin Injury: Patient experienced an abrasion, reddened skin, skin tear, or laceration.

-

Musculoskeletal Injury: Patient experienced a fracture or tendon injury.

-

Soft Tissue Injury: Patient experienced swelling, bruising, superficial hematoma, or surgical wound bleeding and/or dehiscence.

-

Brain Injury: Patient experienced a hemorrhagic contusion or subdural hematoma.

Discharge Plan Outcome. We examined the outcome of the planned discharge following the fall to determine whether the patient was discharged as intended or the fall resulted in a delay or change to the discharge plan.

-

Discharged as Planned: The patient’s discharge plan was unchanged due to the fall.

-

Not Discharged as Planned: The patient was unable to be discharged at the time intended or needed to be readmitted due to the fall.

Staff Presence/Assistance. We analyzed the report details to determine whether a staff member was present and/or assisting the patient when the fall occurred.

-

Staff Was Present and Actively Assisting the Patient: A staff member was providing hands-on assistance to the patient when the fall occurred (e.g., assisting with ambulating or transferring).

-

Staff Was Present but Not Actively Assisting the Patient: A staff member was with the patient but was not providing hands-on assistance (e.g., staff member was in the room, but not helping the patient ambulate) when the fall occurred.

-

Staff Was Not Present: A staff member was not with the patient at the time the fall occurred.

Descriptive Data Analysis

We used a retrospective, mixed-methods design with an exploratory sequential approach,23 starting with a focus on the qualitative data, which was then quantified for further analysis. The variables were measured by frequency and assessed using a descriptive data analysis. Descriptive analysis is a quantitative method where phenomena are explored and patterns are identified with the purpose of better understanding and explaining the occurrence of the phenomena.24 This type of analysis is not used to identify causal relationships but is used to characterize the context of the phenomena, point toward possible causal mechanisms, and generate hypotheses.

Statistical Analysis

We used a two-proportion z-test to compare the proportion of serious events in the group of falls surrounding discharge to the proportion in the comparison group. The statistical test was used to determine whether the proportion of serious events in the falls surrounding discharge group was significantly greater than that in the comparison group using a 0.05 level of significance.

Results

Event Classification

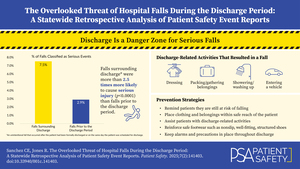

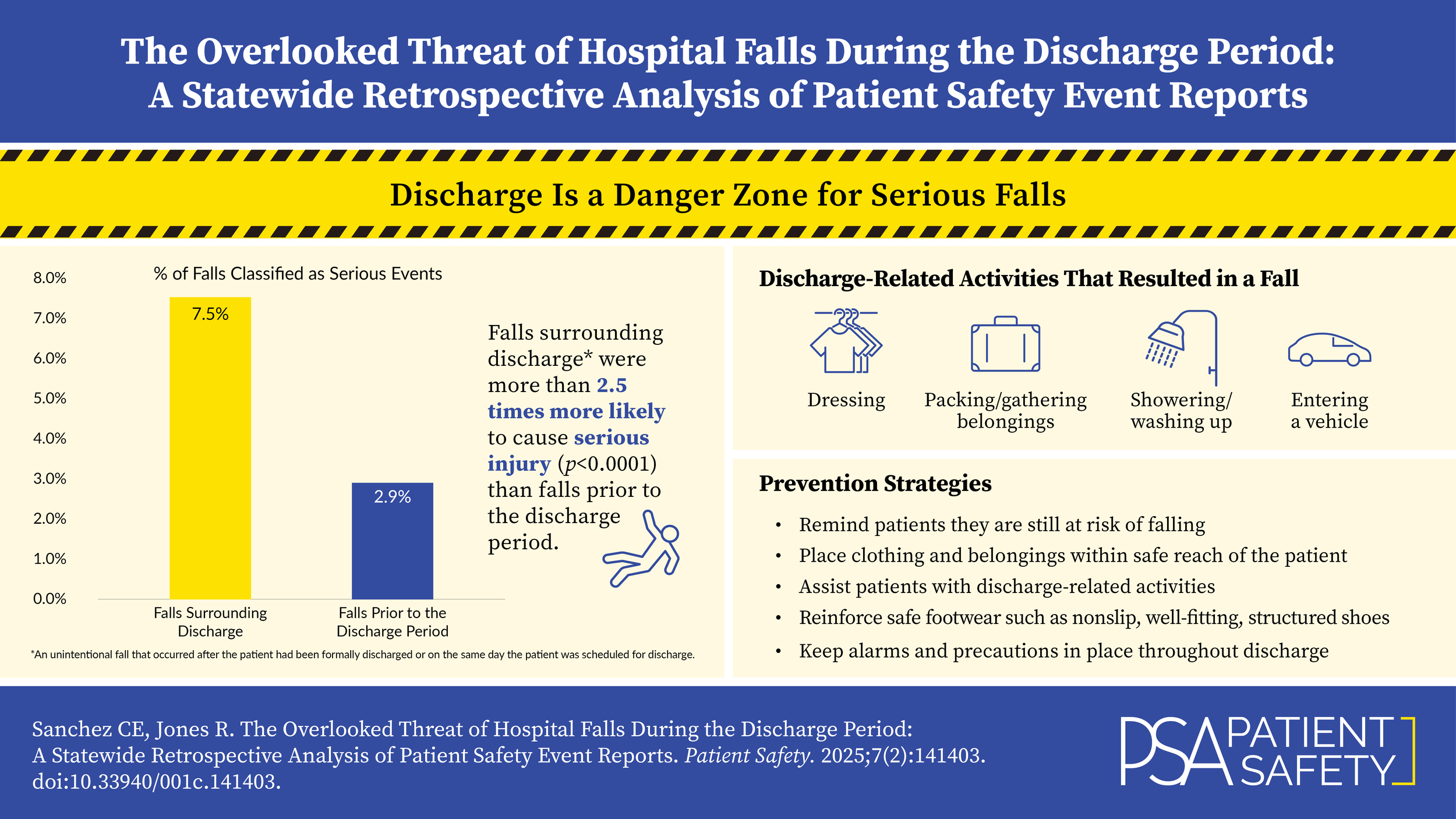

In the falls surrounding discharge group, 7.5% (19 of 253) of the reports were classified as serious events. This was significantly greater than the comparison group, in which only 2.9% (749 of 25,701; p<0.0001) were serious events.

This quantitative analysis revealed a significantly greater proportion of serious events among falls occurring around the time of discharge compared to those in the broader comparison group. The sections that follow describe the characteristics and contextual factors of the falls surrounding discharge group in greater detail.

Patient Characteristics

Among patients who experienced a fall surrounding discharge, sex was reported in 232 reports. Of these, 53% (123 of 232) were female and 47% (109 of 232) were male. Age was provided in all but one report, with a mean age of 68.4 years and a median of 73 (range=1–105 years; 25th percentile=59 years; 75th percentile=81 years). Over two-thirds of patients (69.4%; 175 of 252) were 65 years or older. Among patients age 65 and older, 8.6% (15 of 175) of falls were reported as serious events, compared to 5.2% (4 of 77) in patients under 65 years of age.

Fall risk status was able to be determined in 151 reports, with over three-quarters (76.8%; 116 of 151) indicating that the patient was at risk for falls. Fall history information was available in 115 reports, with approximately half (50.4%; 58 of 115) reflecting a prior history of falls.

Fall Type

All reports provided sufficient detail to identify the fall type. Falls occurring while ambulating were most common (33.2%; 84 of 253). Figure 2 illustrates the frequency of each identified fall type.

We also investigated the relationship between fall type and event classification. As shown in Table 1, seven of the 11 fall types identified in this study resulted in at least one serious event.

Further analysis of fall types revealed that 20.6% (52 of 253) of falls were associated with activities more closely related to the discharge process than to routine patient care. These activities included dressing, packing/gathering belongings, showering/washing up, and entering a vehicle. Among these discharge-related activities, dressing was the most frequently identified, accounting for 10.3% (26 of 253) of all falls. One notable report highlighted the patient’s perception of risk: After falling, the patient stated they believed they could dress independently because of their imminent discharge.

Footwear also emerged as a contributing factor to falls around the time of discharge. Five falls were associated with footwear issues: two while ambulating, two in the hallways of facility, and one on the grounds of facility. Issues related to footwear included patients tripping over their shoes, wearing less supportive footwear (i.e., flip-flops), and wearing an ill-fitting surgical shoe.

Discharge Phase

All reports contained sufficient detail to determine the patient’s discharge phase at the time of the fall. More than one-quarter of patients (28.5%; 72 of 253) were in the discharge complete phase when their fall occurred, as shown in Figure 3.

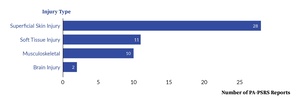

Injury Type

A total of 185 reports contained sufficient information to determine whether an injury occurred (see Figure 4). Among these, 15.1% (28 of 185) described a superficial skin injury, such as skin tears and lacerations; 5.9% (11 of 185) involved a soft tissue injury, including superficial hematoma and surgical wound bleeding or dehiscence; 5.4% (10 of 185) reported a musculoskeletal injury, including various types of fractures; and 1.1% (2 of 185) resulted in a brain injury, including one patient who was diagnosed with a hemorrhagic contusion and another with multiple subdural hematomas. The remaining 134 reports indicated that no injury occurred.

Discharge Plan Outcome

Information about the discharge plan outcome was available in 141 reports. The majority (80.9%; 114 of 141) of these indicated that the patient was discharged as planned, while 19.1% (27 of 141) of patients were not discharged as planned.

Staff Presence/Assistance

Information regarding staff presence and assistance at the time of the fall was included in 206 reports. Among these, 71.8% (148 of 206) indicated staff was not present at the time the fall occurred. In 18.4% (38 of 206), staff was present but not actively assisting the patient, while in 9.7% (20 of 206), staff was present and actively assisting the patient.

Discussion

Implications of Findings

Consistent with prior research,25–28 our findings confirm that inpatient falls can lead to patient injury. Our study builds upon existing literature by highlighting the period surrounding hospital discharge as a critical transitional phase for fall and injury prevention. We identified a statistically significant difference in the proportion of serious events between falls surrounding discharge and those in the comparison group. Notably, serious events occurred in 7.5% of falls surrounding discharge, more than double the proportion in the comparison group (2.9%). Additionally, we identified discharge-related activities, including dressing, packing/gathering belongings, showering/washing up, and entering a vehicle, which could be potential targets for prevention strategies during this critical period. Taken together, these findings suggest that the discharge transition period warrants the same level of attention—if not greater—as any other phase of hospitalization to prevent falls and mitigate the risk of serious injury when falls do occur.

The data from this study suggest that patients may underestimate their risk of falling during the time surrounding discharge. Patients may feel that because they are being discharged, they are no longer at the same risk as they were during their hospital stay. This is supported by the example in our dataset of a patient who did not ask for help getting dressed, believing they were independent due to their imminent discharge. While hospital discharge indicates clinical stability sufficient to leave inpatient care, patients may not be fully recovered or at their baseline level of functioning and may remain at risk for falling during this transitional period.16,17,29 Additionally, time in the hospital and recovering from injury and/or illness can leave patients weaker than they were prior to hospitalization,16,17,29 but patients may not perceive this weakened state.30 Patients should be informed that, although they no longer require inpatient hospital care, they may still be at risk of falling.

The results of this study underscore the importance of integrating fall prevention into discharge planning and instructions. Discharge planning, which should begin early in a patient’s hospital stay, is primarily intended to determine the type of care a patient will need after they leave the hospital and to ensure safe patient transfer to their discharge destination (e.g., home, skilled nursing facility).19,31 This includes medication reconciliation,32,33 necessary health resources (e.g., home health, physical therapy, medical equipment),19,31 and patient33 and caregiver education19 about fall prevention at their post-discharge destination. Notably, more than one-quarter of patients in our study had technically been discharged at the time their fall occurred. These patients would have already received their discharge information and instructions, highlighting an opportunity to remind patients to keep inpatient fall prevention strategies in place until they leave hospital grounds. Embedding fall prevention into both the discharge plan and discharge instructions may help bridge the gap between inpatient and post-discharge fall prevention efforts.

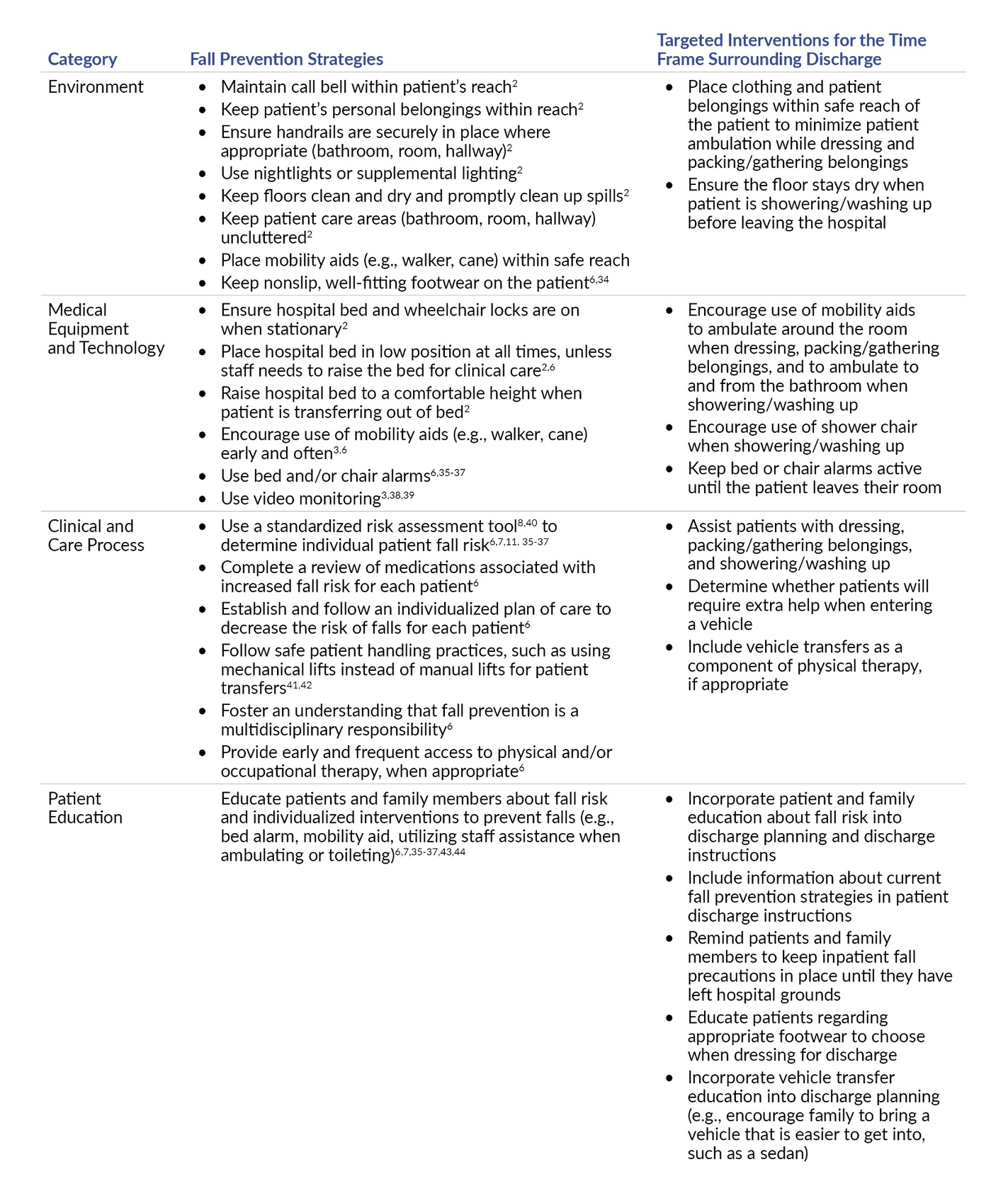

Potential Safety Strategies

Table 2 outlines evidence-based fall prevention strategies identified in the literature. These interventions are applicable throughout the hospital stay and should be consistently maintained through the discharge period until the patient has left hospital grounds. The third column illustrates how existing evidence-based fall prevention strategies can be adapted to target the time frame surrounding discharge.

Future Directions

Future research should explore both patient and staff awareness and perceptions during the time frame surrounding discharge, as well as implementation and evaluation of targeted fall prevention strategies during this transitional period. Safety strategies should be assessed for feasibility (e.g., time and resources required to implement and maintain), potential unintended consequences, and effectiveness in reducing falls surrounding discharge.

Limitations

The quality of information provided in the free-text fields of PA-PSRS reports varies, with some reports containing more detailed information than others. This reduced the full scope of certain variables in our study. When using the PA-PSRS Falls Event Type Decision Tree to code fall type, we were also limited by the algorithm’s linear design and dichotomized (yes/no) options. Fall types positioned earlier in the decision tree are more likely to be selected than types that may also be relevant but do not appear until further along in the coding sequence. Additionally, the number of falls that occurred during the discharge period may be underrepresented in this study, as some reports may not have included keywords or sufficient detail in the free-text fields to determine that the fall occurred on the day of discharge. As a result, relevant cases may have been missed during data extraction and manual review. Due to the large volume of reports in the comparison group, manual review for additional discharge-related indicators was not feasible. Finally, the fall prevention strategies provided in Table 2 are not exhaustive, as we did not intend to provide a full review of all fall prevention strategies and their effectiveness.

Conclusion

This study highlights the time frame surrounding discharge as a critical and high-risk period for falls, representing a greater threat to patient safety than previously recognized. Our analysis revealed that a significantly greater proportion of serious events resulted from falls during this period, with falls surrounding discharge involving more than double the proportion of serious events compared to the broader comparison group. We also identified discharge-related activities that can serve as focus points for interventions targeting this critical phase of care.

These findings underscore the importance of maintaining vigilant fall prevention efforts throughout the discharge process, up to and including the patient’s departure from hospital grounds. By addressing the vulnerabilities identified in this study, healthcare facilities can enhance patient safety and reduce the risk of serious fall-related events during the discharge period.

Notes

This analysis was exempted from review by the Advarra Institutional Review Board.

Data used in this study cannot be made public due to their confidential nature, as outlined in the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error (MCARE) Act (Pennsylvania Act 13 of 2002).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kelly Gipson and Rick Kundravi for their guidance in identifying relevant fall prevention strategies and for providing reliable resources that supported the inclusion of these strategies in this manuscript. We also thank Shawn Kepner for his statistical expertise and for conducting the statistical test for this study.

About the Authors

Christine E. Sanchez (chrsanchez@pa.gov) is a research scientist on the Data Science & Research team at the Patient Safety Authority. She is responsible for utilizing patient safety data, combined with relevant literature, to develop strategies aimed at improving patient safety in Pennsylvania.

Rebecca Jones, director of Data Science & Research for the Patient Safety Authority, leads a multidisciplinary team advancing safety science through rigorous research, advanced data analysis, and systems-based approaches. She has authored over 40 peer-reviewed articles and served on national expert panels with organizations such as the National Quality Forum and Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine. A registered nurse with an MBA in healthcare management and certifications in patient safety, human factors, and risk management, she focuses on applying data-driven insights to strengthen system safety and human performance in healthcare.

PA-PSRS is a secure, web-based system through which Pennsylvania hospitals, ambulatory surgical facilities, abortion facilities, and birthing centers submit reports of patient safety–related incidents and serious events in accordance with mandatory reporting laws outlined in the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error (MCARE) Act (Act 13 of 2002). All reports submitted through PA-PSRS are confidential and no information about individual facilities or providers is made public.

Within PA-PSRS, the event reporter chooses among 168 care areas to indicate the location where an event occurred. To simplify our analysis, we sorted each of the care areas into 23 higher-level care area groups, 10 of which were relevant for this study.

“Discharg” was used to search for discharge, discharged, discharging, and any other conjugation of the word that may have been included in the free-text fields of the event report.

Fall risk was determined based on responses to the optional Fall Event Detail Question in PA-PSRS: “At the time of last assessment, was patient determined at risk?” When this question was not answered by the reporter, but event details indicated the patient was at risk for falls, the researcher coded the reports accordingly.

Fall history was determined based on responses to the optional Fall Event Detail Question in PA-PSRS “Does patient have prior history of falls in the past 12 months?” When this question was not answered by the reporter, but the event details indicated the patient had a history of falls, the researcher coded the reports accordingly.

In the Falls Event Type Decision Tree, the other category includes a range of fall types, some of which are more specific. One such type, unanticipated physiological fall (“physiological”), was pertinent to the reports in our study and was therefore treated as distinct from the broader other fall type. Falls categorized under the more general “specify the reason” subtype remained within the other fall type category.

Serious events were identified using the structured event classification field assigned by the reporting facility, while injuries were manually coded based on details provided in the unstructured free-text event descriptions. Although there is a natural overlap between serious events and injuries, not all injuries were classified as serious events, as some may not have required the delivery of additional healthcare services.