Electrosurgery is used to rapidly cut soft tissue and control bleeding during a variety of surgical procedures.1–3 Some commonly reported complications from electrosurgery include electrical burns,1,4,5 surgical fires,1,5,6 electric shock,4 and malfunction of implanted medical devices such as pacemakers.4 A review of event reports recently submitted to the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting System (PA-PSRS) identified complications that were less commonly referenced when reviewing the literature about electrosurgery complications: burns from a metal instrument that was in contact with the electrosurgical unit (ESU) and skin injuries from the ESU grounding pad. Knowledge about the principles of electrosurgery2 and how ESUs work2,7 can help prevent complications that may pose a risk to patient safety.

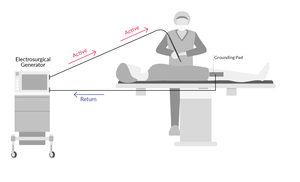

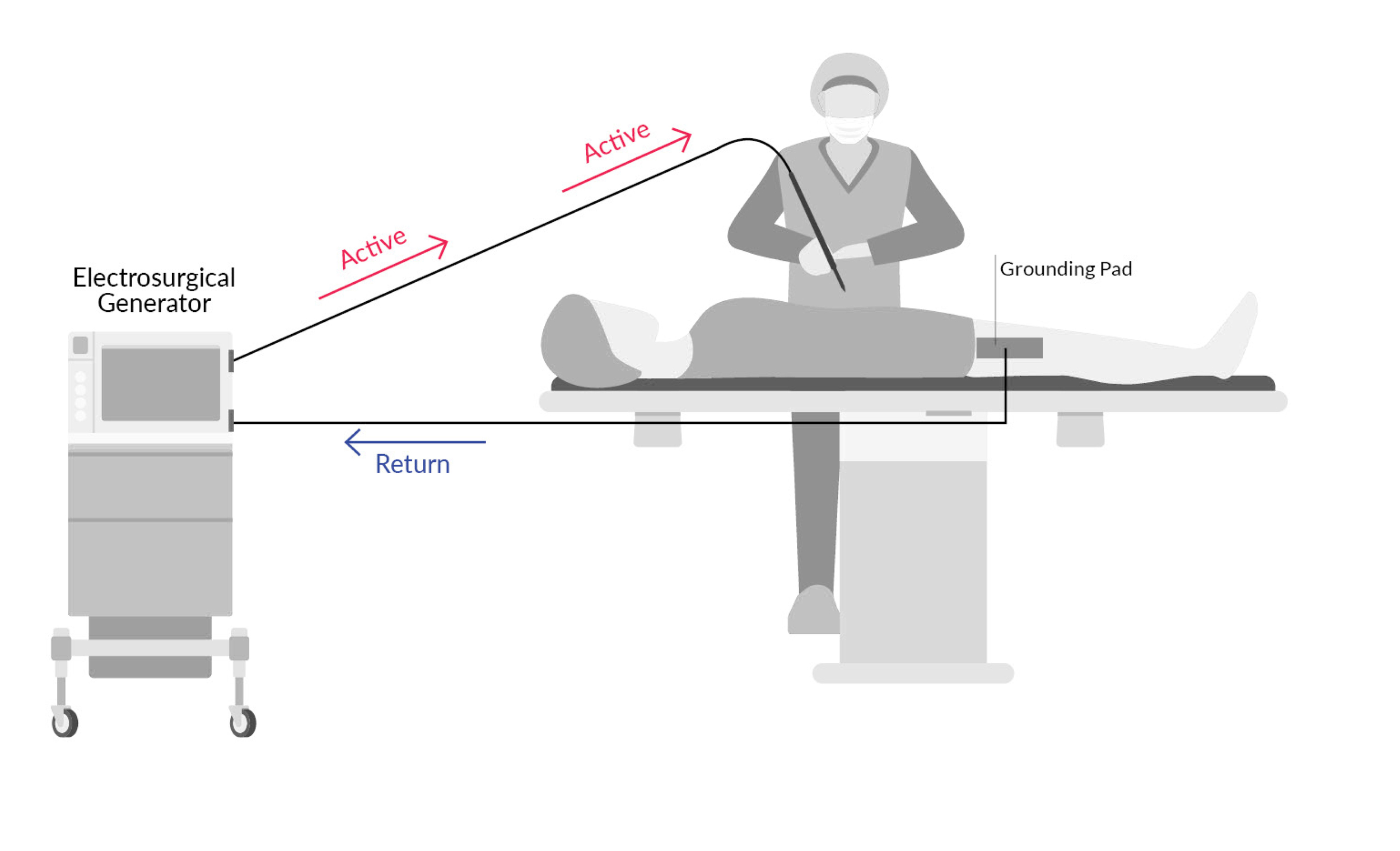

An electrosurgery generator unit powers an electrical current that flows through the cutting and/or coagulation instrument. There are two electrosurgery modalities, monopolar and bipolar.2,4 Monopolar electrosurgery (Figure 1) is the most common modality used in surgical procedures. In monopolar electrosurgery, the handheld device (the device used by the surgeon) is pencil shaped, with a single tip. The current flows from the generator to tip and then into the patient’s tissue. The current then exits the patient via a grounding pad that is adhered to the patient’s body to complete the electrical circuit and flows back to the generator.2,4,8

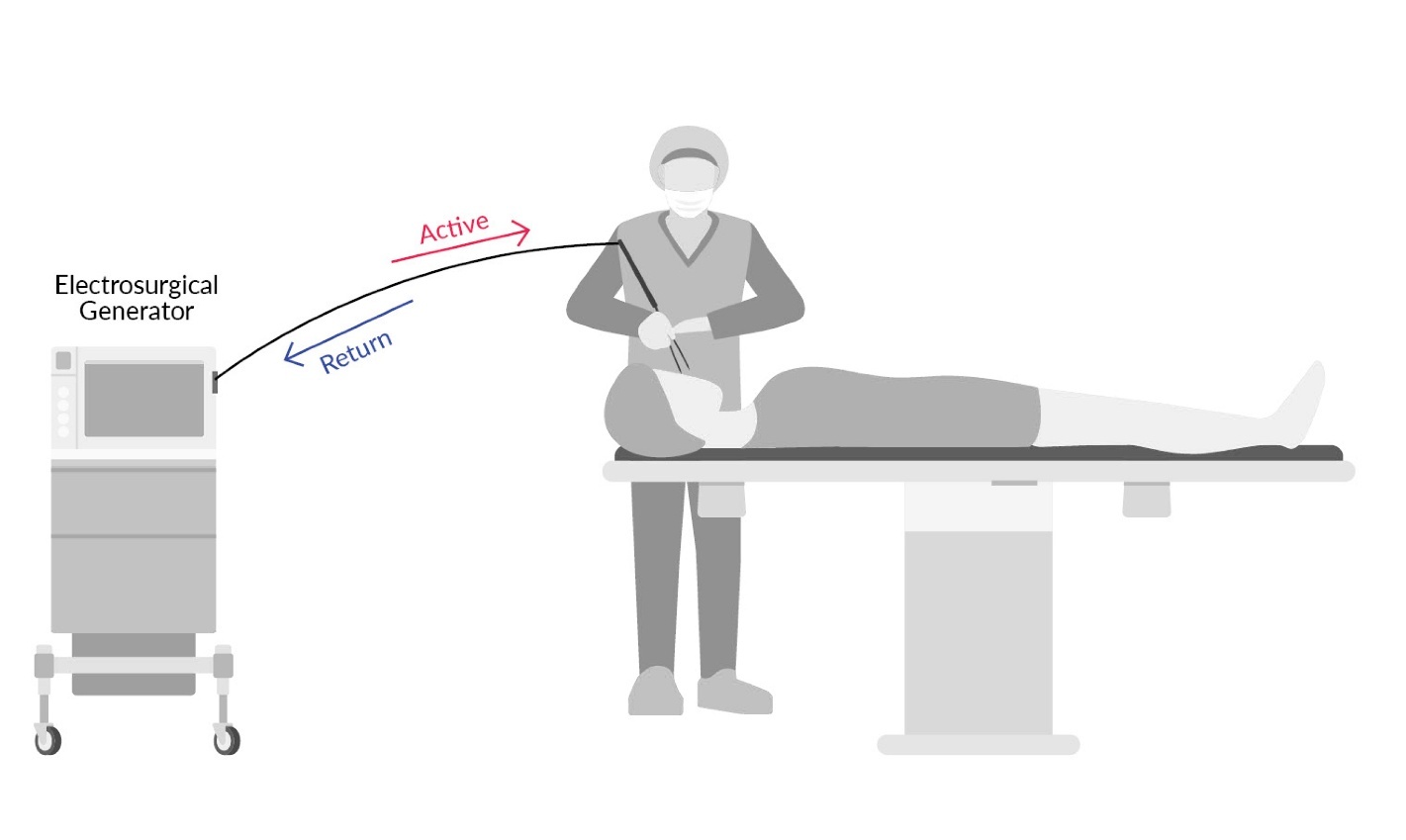

Bipolar electrosurgery (Figure 2) is most commonly used in neurosurgery and surgeries involving the eyes and eyelids.8 In bipolar electrosurgery, the handheld device is designed similar to tweezers. The electrical current travels from the generator to one prong of the handheld device, across the patient’s tissue surface to the prong on the other side of the handheld device, and then back to the generator.2,4,8 An electrical current does not pass through the patient, so a grounding pad is not needed.

Two reports submitted to PA-PSRS described burns to the patient from another metal surgical instrument. One burn resulted from the ESU electrical wire that was clamped down using a metal clamp. The energy running through the wire likely caused the clamp to heat up. This clamp was then inadvertently leaned on, causing it to touch the patient’s skin and subsequently leave a burn mark on the patient that required topical treatment. Another example described the ESU coming into contact with a metal retractor, which caused the retractor to become hot, subsequently burning the patient at the point of contact between the patient’s skin and the retractor.

The heat transfer to the metal clamp and/or retractor that resulted in a burn could have been due to faulty ESU instrument insulation.2 One previous study cited that skin contact with metals, such as body piercings, can cause burns from the metal jewelry coming in contact with ESUs with compromised insulation,9 allowing the electrical current to transfer from the surgical instrument to the metal object.2 It is important to note, however, that the integrity of the instrument insulation was not included in the event reports.

Another complication in recent PA-PSRS reports included burns and skin tears from the adhesive return electrode (i.e., grounding pad). Burns from the grounding pad can occur when the pad becomes partially detached from the patient, and skin tears were reported to occur when the grounding pad was removed after the procedure was complete.

Burns from the grounding pad can be prevented by using a return electrode monitoring system. In addition, placing the grounding pad on a well-perfused, dry, hairless area of the body that is over a large muscle and as far away from metallic implants as possible can decrease the risk of burns and skin tears when the pad is removed.2 There is also an option to use a full-body return electrode that reduces the risk of burns and skin tears because it is not adhered to the patient’s skin. These full-body return electrodes are not suitable for all patients, as they can cause inadvertent discharge of an implantable electronic device, such as an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.10 With that caveat in mind, if a patient is at an increased risk of a skin tear when a grounding pad is removed (e.g., thin skin), or is otherwise generally a good candidate for a full-body return electrode pad, using one during their procedure can increase patient safety.

To minimize the likelihood of the complications discussed above, surgeons and other surgical staff can:

-

Understand how ESUs transfer heat and energy.

-

Inspect ESUs for faulty insulation, both visually and with the use of a testing wand.2

-

Avoid ESU contact with any metals during the procedure2 to prevent burns to the patient from those metal objects.8

-

Be aware of their surroundings and body positioning throughout a procedure.

-

Understand proper use and placement of the grounding pad.

-

Consider whether a patient would be a good candidate for a full-body return electrode instead of a grounding pad.

Implementing the risk mitigation strategies described above can increase patient safety and reduce harm during procedures in which ESUs are used.

Disclosure

The author declares that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

This article was previously distributed in a July 16, 2025, newsletter of the Patient Safety Authority, available at https://patientsafety.pa.gov/newsletter/Pages/newsletter-july-2025.aspx.

About the Author

Christine E. Sanchez (chrsanchez@pa.gov) is a research scientist on the Data Science & Research team at the Patient Safety Authority. She is responsible for utilizing patient safety data, combined with relevant literature, to develop strategies aimed at improving patient safety in Pennsylvania.