Introduction

Electrolyte imbalances in pediatric oncology patients result from disease processes as well as treatment and may present an oncologic emergency.1 The administration of intravenous (IV) electrolytes is a crucial aspect of supportive care the registered nurse (RN) provides.2 The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) includes IV magnesium sulfate, IV potassium chloride, and IV potassium phosphate among its list of high-alert medications which have a “heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when they are used in error.”3 ISMP recommends strategies to reduce risk of errors related to high-alert medications, including standardizing ordering and administration methods and implementing redundancies.3

Available Knowledge

A “smart pump” is an infusion pump equipped with dose error reduction system (DERS) software and drug libraries designed to reduce dose and rate infusion errors.4 They are used in all inpatient areas across our hospital. Smart pumps may reduce incorrect programming errors but have not eliminated IV medication infusion errors.5 Even when the RN uses smart pump integration with the drug library, wrong infusion rate errors can occur if the RN overrides the “soft” limit alert for infusion rates.6 In an observational study of 10 U.S. hospitals where smart pumps were in use, infusion rate errors were the most frequent type of serious IV medication administration errors.5 In another study documenting IV infusion deviations from a prescriber’s order or the hospital’s policy, 7.6% of the 2,008 IV infusions were administered at a different rate than ordered.7 The authors concluded that many deviations did not cause patient harm, and nurses deliberately used deviations to improve efficiency in care delivery.7 Not all deviations represented errors, but normalized discrepancies in the infusion rate can represent system weaknesses, risk for serious error, and opportunities to modify policy to match the reality of the care environment.7

Problem Description

Nurse leaders at our pediatric hospital were concerned that the variability in nursing practice on the two oncology units and lack of detail in existing policy for this subset of high-risk IV infusions could lead to patient harm events. Furthermore, it was challenging to teach all RNs on the units the method to administer electrolyte boluses (EB), as the steps were complex and methods varied between nurses. The most frequently administered EBs were in scope for this improvement initiative and included IV magnesium sulfate, potassium chloride, potassium phosphate, and calcium gluconate. Despite calcium gluconate not being recognized as a high-alert medication by ISMP, the team chose to include it in this initiative to highlight standardization for all institution-specific dual sign-off EBs.

Specific Aims

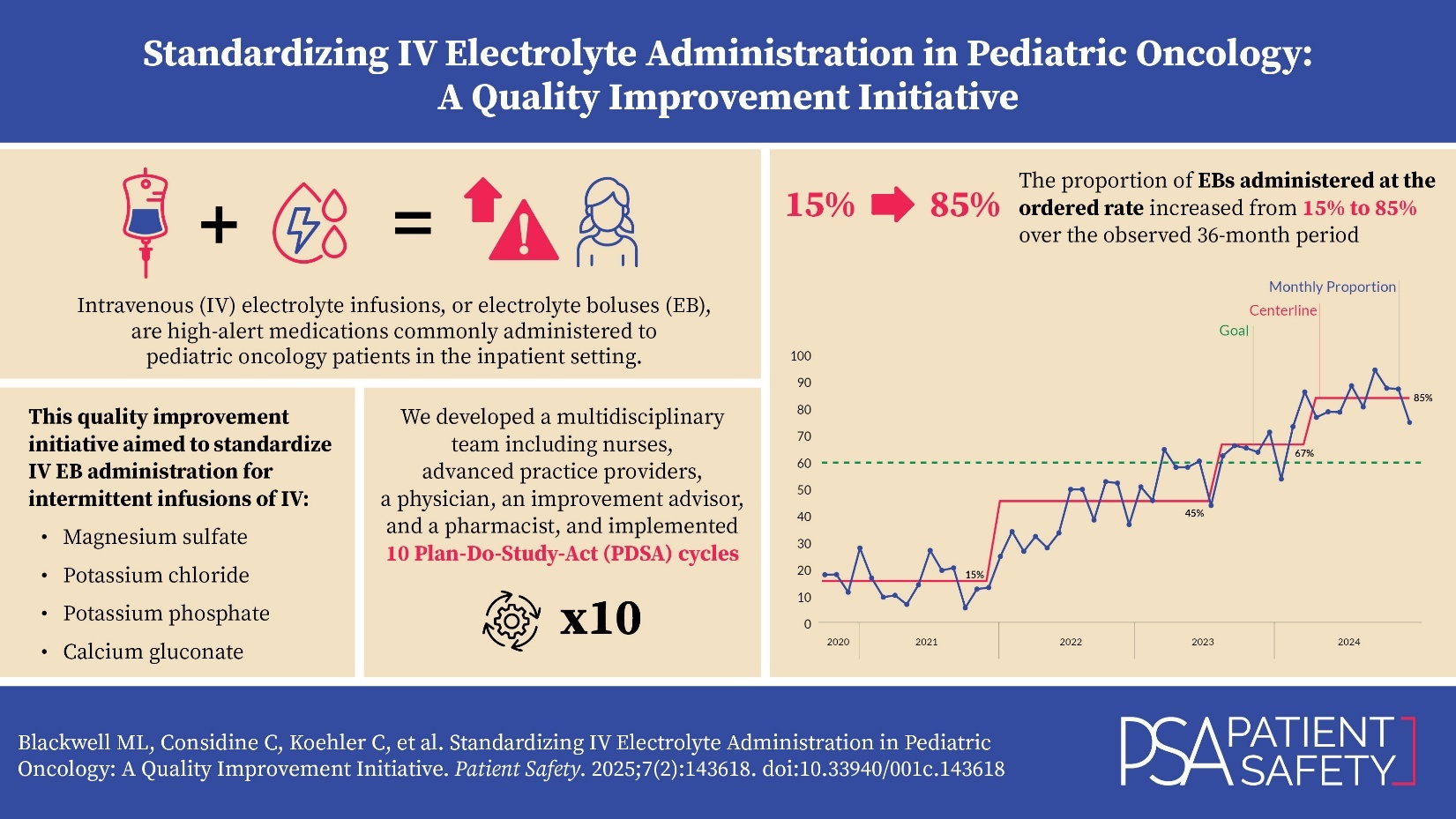

The global aim of this improvement initiative was to improve the quality and safety of care by standardizing IV electrolyte administration in the inpatient pediatric oncology setting. To determine if the interventions led to an improvement, the proportion of times that the EB documented infusion rate matched the ordered infusion rate was measured. Our improvement team set the specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) aim: to increase the proportion of administrations where the documented EB infusion rate matches the ordered EB infusion rate from a baseline of 15% to a goal of 60% by March 1, 2024, for all administrations of IV magnesium sulfate, potassium chloride, potassium phosphate, and calcium gluconate in the pediatric oncology units. We chose the goal of 60% because of the many barriers to compliance, and because we viewed it as achievable within a limited period of time. This article was written according to Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQuIRE) 2.0 guidelines, as it provides a framework for reporting quality improvement methods and outcomes.8

Methods

Context

Our institution’s main hospital is a 600-bed urban, freestanding, academic, quaternary care children’s hospital. There is a combined total of 51 beds in the two inpatient pediatric oncology units (bone marrow transplant and general oncology) that are staffed by approximately 130 RNs. For high-risk medications including EBs, our institution requires an independent double check by two RNs; each RN is responsible to determine that the ordered medication is safe for the patient before starting the IV infusion. The hospital policy requires the RN to infuse the EB at the ordered infusion rate (milliliters per hour) and duration of infusion. The institution’s policy for EB administration prior to beginning this improvement project outlined steps for performing a two-clinician independent check, necessary equipment, proper selection of medication from the pump’s drug library, IV line/pump check, and documentation. RNs on the inpatient oncology units administered 623 EBs during a 15-month baseline period from October 1, 2020, to December 31, 2021. During this baseline period, the proportion of administrations in which the EB infusion rate matched the ordered infusion rate was 15%, representing variation in nursing practice, methods not supported by hospital policy, and a disconnect between the provider’s order and the RN’s actions.

Interventions

A multidisciplinary improvement team was formed with stakeholders from each stage of the drug delivery process. The seven-person team included a nurse leader, a frontline RN, two nurse practitioners, a clinical pharmacist, a physician, and an improvement advisor. The team used the organization’s improvement framework, which is based on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Model for Improvement, which breaks improvement projects into steps, including forming a team, establishing aims and measures, testing and implementing changes, and finally sustaining and spreading changes.9 Improvement tools used included a project charter, metric definition, fishbone diagram, driver diagram, impact/effort matrix and Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

Current state process maps of the ordering provider, the pharmacist, and the RN’s workflow in ordering, verifying, and administering EBs were developed. The RN process maps illustrated the multiple steps involved in EB administration, which varied among the four different EBs, adding to the complexity of the problem. Additionally, a shared mental model did not exist between the ordering provider and RNs regarding concurrently infusing electrolyte-containing fluids or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) with EBs. Order verification pharmacists used a standard operating procedure to verify all medication orders including EBs. As order verification pharmacists are not at the bedside, their workflow was outside the scope of this project.

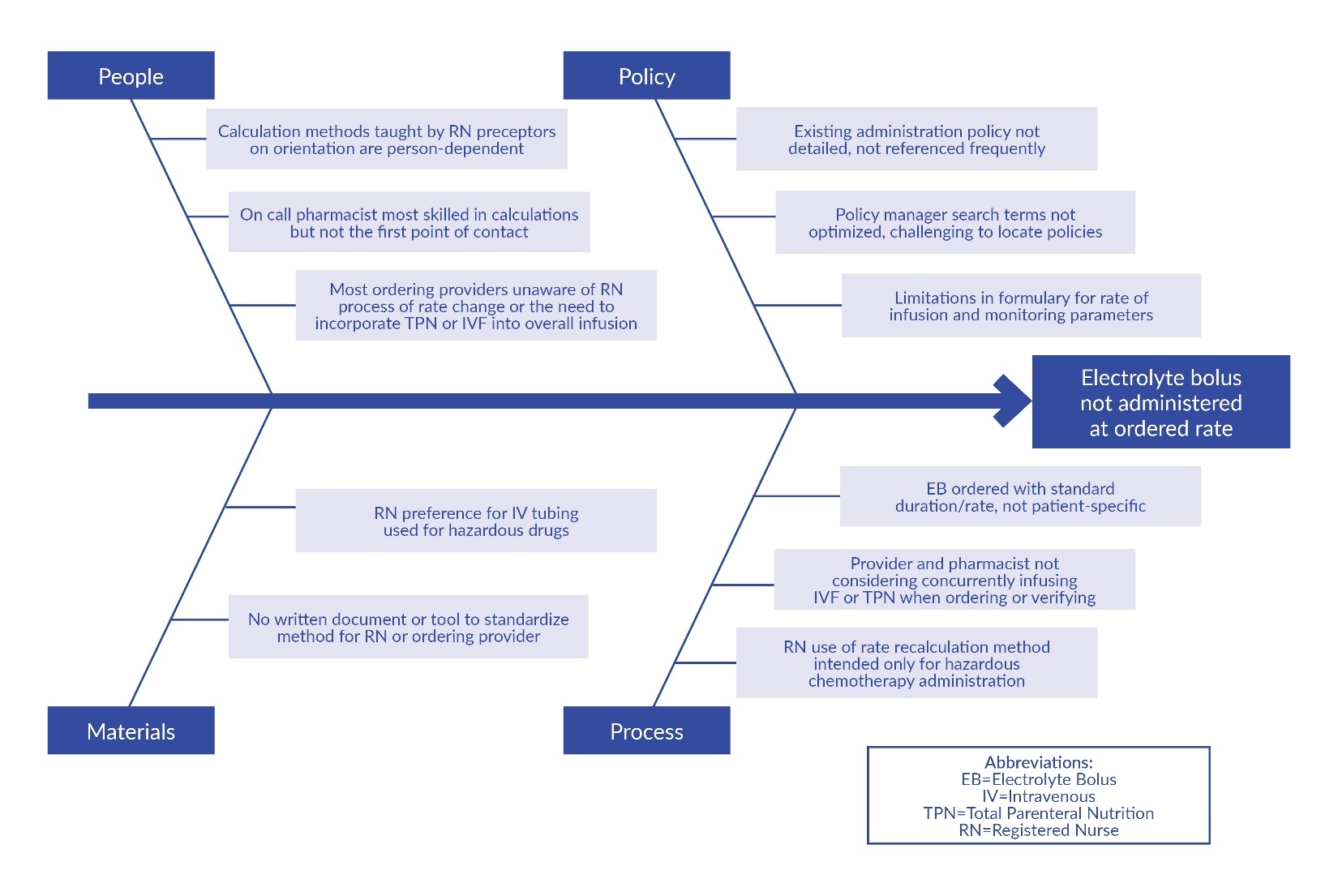

When the administration rate did not match the order, the team sought to understand the discrepancy and to introduce interventions that would create more standardization. The team gathered information in several ways, including through a survey of RNs on the oncology units, chart review, and direct observation. Based on this information, the team developed a fishbone diagram detailing barriers to standardization related to people, policy, materials, and processes (Figure 1).

A total of 59 inpatient oncology RNs completed a voluntary survey in June 2020. The RN survey included a binary-choice question asking whether the RN could complete an independent check independently or whether they were unable to complete steps independently. Of the 59 RN respondents, 39% (n=23) reported they could not complete an independent check of EBs due to lack of clarity in the process and instead relied on the second RN to assist in calculations before administration. RNs reported an inability to confirm the safe duration of infusion independently, especially when the IV electrolyte was infused concurrently with TPN or other electrolyte-containing fluids. Often nurses would call a pharmacist for support in calculations. The survey also included open-ended questions about challenges and potential solutions to EB administration. The results highlighted an overall need for more detailed written guidance to instruct the RN on the correct methods to calculate EB infusion rate.

The nurse leader conducted a chart review of the 39 EB administrations in September 2021 in which the RNs’ documented rate did not match the ordered rate. Using a Pareto chart to analyze the chart review data of these 39 EB administrations, the team found that the most frequent reason (55%) for rate changes was due to the practice of rate recalculation intended for hazardous drugs. The second most frequent reason (27%) was that RNs decreased the magnesium sulfate infusion rate to avoid vital sign monitoring required by our hospital’s formulary if infused in less than two hours. Less frequent reasons included RNs increasing potassium phosphate or potassium chloride infusion rates to maximize efficiency (12%) and RNs decreasing the EB infusion rate to account for concurrently infusing electrolyte-containing fluids (6%).

The team discovered that medication rate recalculation was normalized among RNs on the units, as rate recalculations were needed for chemotherapy administration per institutional guidelines. This hospital uses hyper-priming for all large-volume pump IV hazardous chemotherapy infusions. Hyper-priming, or “quick prime,” is the process of rapidly infusing diluent to reduce the dead space in the administration set.10 This method of administration requires the RN to recalculate the rate of administration for all IV hazardous chemotherapy. In these instances, correct infusion rate for IV chemotherapy differs from the rate ordered by oncology providers and verified by pharmacists. Through direct observation and chart review, the team recognized that RNs used infusion rate recalculations intended only for IV chemotherapy administration for other IV infusions, including EBs.

The team brainstormed interventions to address some of the identified barriers to standardizing EB administration and used an impact effort matrix to prioritize and select interventions for implementation (Table 1). We carried out interventions in a series of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles,11 and the team evaluated each intervention based upon clinician feedback.

Interventions

In January 2022, PDSA 1 was implemented, which consisted of nurse leaders successfully administering 15 EBs without hazardous drug tubing or rate recalculations. This intervention was selected first to build confidence in RNs and RN leaders that EBs could be administered without the processes used for IV hazardous chemotherapy administration. PDSA 2, implemented in March 2022, involved the following:

-

Sharing EB administration information at RN huddles and through email

-

Instructing RNs to administer EBs at the ordered rate

-

Instructing RNs to contact the ordering provider if the RN determined the ordered rate was incorrect or unsafe

In May 2022, for PDSA 3, the team created and posted on both units a document titled “The What and Why Behind Large Volume Electrolyte Bolus Administration,” which outlined the RN’s process of large-volume pump EB administration along with the reasoning behind each step. Our interprofessional improvement team then developed four job aids intended for use by RNs, one for each of the four EBs. The job aids were formatted to the organization’s policy template. These job aids described each step of checking the EB order before administration, including confirming the correct indication, dose, concentration, duration, and rate. Additional steps were included if the electrolyte was infused with TPN or IV fluids that contained the same electrolyte.

Our team tested the calcium gluconate and potassium chloride job aids with RNs in October 2022, after dissemination via paper copies and email. In PDSA 4 in December 2022, the team clarified text in the calcium gluconate formulary monograph to differentiate between the intensive care unit (ICU) duration of infusion (30 to 60 minutes) and the non-ICU duration of infusion (60 minutes). The team continued to revise the job aids based on RN feedback. Next, the team added the calcium gluconate and potassium chloride job aids to the existing “Administration of IV Electrolytes” policy (PDSA 5) in January 2023. For PDSA 6 in February 2023, we added a hyperlink to the job aids within their respective monographs in the online hospital formulary to increase RN access and awareness of the job aids.

To address the provider ordering process, the team developed four “ordering guide” documents, one for each of our in-scope EBs, describing each step for the provider to order the EB. The ordering guides included additional steps for the ordering provider if the electrolyte was infused with TPN or IV fluids containing the same electrolyte. In PDSA 7, all four ordering guides were shared with the inpatient oncology advanced practice providers (APPs) in April 2023.

In October 2023, we completed PDSA 8 by publishing the potassium phosphate and magnesium sulfate job aids into the policy after sharing them with frontline nurses and modifying the job aids based on RN feedback. In November 2023, nurse leaders presented a proposal at this institution’s Drug Use Evaluation (DUE) committee to eliminate vital sign monitoring for IV magnesium sulfate in which the duration of infusion was greater than or equal to one hour. A literature review and critical appraisal of the evidence demonstrated no indication for vital sign monitoring, as hypotension or other adverse reactions were not observed for adult or pediatric patients treated with infusions of IV magnesium sulfate greater than or equal to one hour duration.12–17 The interprofessional DUE committee approved the proposal and, subsequently, the drug formulary was modified to remove required vital sign monitoring for infusions of one hour duration or greater (PDSA 9) in January 2024. In the same month, the team completed PDSA 10 by adding a hyperlink to the potassium phosphate and magnesium sulfate job aids within their respective formulary monographs.

Study of Interventions

Fifteen months of baseline data on EB administration were extracted from the electronic health record (October 2020 to December 2021). Data included the medication, date, time of administration, ordered infusion rate, and RN documented infusion rate. The team collated and reviewed EB administration data each month during the intervention period. We compared EB administration during the baseline period with an intervention period from January 2022 to June 2024.

Measures

The outcome measure for our improvement project was percentage of EB administration compliance, defined as the proportion of EB administrations in which the documented infusion rate equaled the ordered infusion rate divided by the total administrations. The documented infusion rate in milliliters per hour (mL/hr) was used as a proxy for infusion duration. When the ordered infusion rate matched the RNs’ documented infusion rate, the administration was considered “compliant.” If the documented infusion rate did not match the ordered infusion rate, the administration was considered “not compliant.” This team audited all infusions of IV magnesium sulfate, potassium chloride, potassium phosphate, and calcium gluconate administered on the inpatient oncology units each month.

The number of times a healthcare worker opened the policy in our organization’s electronic policy manager per month was the process measure. As the RN job aids were added to the “Administration of IV Electrolytes” policy, the number of times a healthcare worker opened the policy was expected to increase. The baseline period for this measure was October 2020 through December 2022, and the intervention period was January 2023 (when the first and second EB job aids were added to the policy) to October 2023 (when the third and fourth EB job aids were added to the policy). We continued to collate the data through April 2024. The team was unable to quantify the unique users accessing the policy or measure the proportion of users who were RNs on inpatient oncology.

A post-intervention survey was distributed to APPs in July 2023 to measure provider satisfaction with using the EB provider ordering guides. The APP survey included the statement “This guide was useful in ordering the electrolyte bolus.” The APP answered using a five-point Likert scale (“strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”). Additionally, the team included one open-ended question to solicit suggested changes to the guides, and one yes/no question asking if the provider would want to use the ordering guide again.

Analysis

The outcome measure was tracked using a statistical process control (SPC) p-chart and the team used SPC rules to interpret special cause variation (Figure 2).18 The eight-point rule (EPR) is one of the 10 rules for identification of special cause variation in Shewhart control charts.19 We used the EPR to evaluate for special cause after implementing our interventions. The process measure was evaluated using a run chart, applying rules for interpretation, including the rule for a centerline shift, defined as greater or equal to six consecutive points above or below the median (Figure 3).20 We evaluated APP satisfaction with ordering guides by collating responses to survey questions.

Ethical Considerations

This project was undertaken as a quality improvement initiative and as such does not constitute human subjects research.

Results

Outcome Measure

The number of EBs administered on the units varied from 17 to 123 per month. During the baseline period, 15% of all EBs were administered at the ordered rate. Eight months after the first intervention, special cause variation was observed, resulting in a positive centerline shift, with 45% of all EBs being administered at the ordered rate. This shift was sustained for 19 months. In August 2023, a second positive centerline shift occurred, with 70% of EBs administered at the ordered rate. In April 2024, a third positive centerline shift occurred, with 85% of EBs administered at the ordered rate.

Process Measure

The “Administration of IV Electrolytes” policy on the hospital’s electronic policy manager was accessed a median of seven times a month during the baseline period. After the first two job aids were embedded within the existing policy in January 2023, the run chart demonstrated six data points above the median, resulting in a positive shift. From January 2023 to April 2024, the policy was accessed a median of 110 times each month. In a voluntary survey in July 2023, all seven of the APPs surveyed responded that they “agree” or “strongly agree” that the “guide was useful in ordering the electrolyte bolus.” After using at least one of the four EB ordering guides in clinical practice, all seven APPs indicated they would want to use the EB guide again.

Discussion

Summary

This quality improvement initiative significantly increased the proportion of EBs administered at the ordered rate, from a baseline of 15% to 85%, surpassing the aim of achieving 60% compliance by March 1, 2024. The first three PDSA cycles yielded modest improvement but were important in gaining the confidence of key nurse leaders on the units and sharing messaging across the frontline nurse team. The most effective interventions included publishing the four RN job aids and changing formulary guidance.

Interpretation

The addition of one job aid for each of the four EBs into the policy was the driving force of this project, as the job aids created a clear, standard approach to verification of the duration and infusion rate. The job aids addressed previously challenging scenarios in a stepwise approach, such as concurrent infusion of TPN. The updated policy also stated that the infusion set is to be primed with the large-volume electrolyte, which was a previously missing step that caused confusion among nurses.

While policy revisions do not always translate to a change in practice, this project was successful in changing the RN administration process because the step-by-step guidance in the job aids made it easier for RNs to complete all necessary steps in the administration process. This team attributes the success of the RN job aids to the expertise of our clinical pharmacist in developing the content, seeking frontline RN feedback, and incorporating suggested changes into the published policy. Five of the improvement team members are clinicians who practice in the inpatient oncology clinical setting. This subject matter expertise allowed the team to understand the processes we aimed to change. Further, by implementing changes into existing electronic systems such as the hospital formulary and adding hyperlinks from the formulary to policy, the frontline clinicians found this information to be readily accessible. In a large, complex healthcare environment, our interventions needed to reach individuals regardless of their awareness of our improvement team or project. We anticipate that these interventions will increase the ability to teach new APPs and RNs who join the care team in inpatient oncology the ordering and administration steps for each EB.

The team attributes the sustainability of the project’s outcomes to the time spent understanding the problem before developing interventions.21 This interprofessional improvement team integrated sustainable interventions into existing systems of care, “hardwiring” interventions into practice using existing workflows including policy and the hospital’s medication formulary.21

Limitations

There were several limitations of the project due to context and measures. In the inpatient oncology units, the influence of hyper-priming and IV hazardous chemotherapy rate recalculation was a primary driver of nursing practice. The variability in medication administration practices the team observed may be less prevalent in less-acute settings or inpatient care settings without frequent infusion rate recalculation of high-risk medication categories.

The outcome measure did not account for the degree of variability between the ordered and administered infusion rate. The infusion rate was used as a proxy for the infusion duration. However, when the administered infusion rate varied slightly, the impact to the infusion duration was not likely to be clinically significant. The outcome measure did not differentiate, for example, between an EB administered too quickly in half of the intended duration and an EB administered too slowly for five minutes longer than the intended duration.

This institution uses an electronic policy manager system which cannot differentiate between categories of healthcare workers or count unique users. Therefore, we could not measure the number of inpatient oncology RNs who opened the “Administration of IV Electrolytes” policy. The team inferred that an increase in healthcare workers opening the policy represented an increase in oncology RN use, as RNs are the primary users of policies published in our policy manager.

Conclusions

The team successfully used a quality improvement framework to implement interventions and improve the proportion of EBs administered at the ordered rate. The team found the gap between the medication order and RN action was an opportunity to explore practice and reduce complexity of care delivery. Reaching 85% compliance in the 11 months after our last PDSA cycles were complete indicates the project’s sustainability over time. Our institution has the potential to spread standardization of medication delivery to other drug categories, such as IV hazardous chemotherapies. Clinical teams outside of inpatient oncology are interested in creating additional job aids to guide the administration of additional high-alert medications such as IV hypertonic saline solution. The team anticipates sustained success in the outcome measure, as interventions were implemented into the organization’s policy and formulary.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

About the Authors

Mary L. Blackwell (blackwellm@chop.edu) is a nurse leader with over 10 years of pediatric nursing experience, including five years in safety and quality leadership at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). She is a manager of nurse leaders and the nurse coleader for preventing falls, venous thromboembolism, and healthcare-associated viral infections across the CHOP enterprise. Blackwell is a certified pediatric nurse and a certified professional in healthcare quality. She holds a Bachelor of Science in nursing and a Master of healthcare quality and safety from the University of Pennsylvania.

Catherine Considine has been an oncology nurse since graduating from Villanova University in 2017. She started her pediatric oncology nursing career with her first job as a bedside nurse at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where she continued to grow her career and became a clinical nurse expert interested in improving efficiencies and creating safer standards of practice. Her passion for this specific demographic of children brought her up to Dana-Farber Cancer Institute to their pediatric unit “The Jimmy Fund.” She has worked as both a nurse navigator and an infusion nurse in this role. She is beginning her master’s in healthcare leadership and management this fall.

Colleen Koehler is a clinical pharmacy specialist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where she has worked for eight years, including six years in oncology and two years as a pediatric generalist. She received her doctor of pharmacy from the University of Illinois Chicago and completed her general year of residency at Rush University Medical Center, followed by her pediatric residency at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Afnan Albahri is a pediatric hospital medicine physician at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). After graduating from Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar, she finished her residency at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University/Nemours Children’s Health Pediatric Residency at the height of the pandemic in 2020. She then worked as a bone marrow transplant and oncology hospitalist for two years at CHOP, where her passion for caring for children with complex medical issues only grew. She currently serves as the medical director of the Mobile Hospitalist Team within the Section of Hospital Medicine at CHOP and specializes in caring for children with medical complexity, with a specific interest in patients with epidermolysis bullosa.

Alison Tardino-Gingrich is a nurse practitioner in oncology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). She started as a nurse at CHOP in 2000 after graduating from the University of Pittsburgh. She received her Master of Science in nursing from the University of Pennsylvania in 2005. She currently works at the King of Prussia campus of CHOP with the general oncology population.

Kimberly A. DiGerolamo is a clinical nurse specialist in oncology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), where she has worked for 23 years. She received her Bachelor of Science in nursing at Holy Family University, Master of Science in nursing at University of Delaware, and doctor of nursing practice (DNP) at Villanova University and is certified as a pediatric nurse (CPN) and pediatric hematology oncology nurse (CPHON). She holds an additional certification in evidence-based practice (EBP) and has been the recipient of several national and local awards, including the Caroline Langstadter Award for Excellence in Nursing and Advanced Practice Provider of the Year Award.

DiGerolamo leads the Falls Prevention Program at CHOP. Her work has been presented at national and regional conferences, and she has authored several papers that have appeared in leading nursing scholarly journals. She is an adjunct instructor in Villanova’s DNP Program. Her love for oncology brought her back to the unit in 2020, where she persistently works to impact healthcare, specifically care of the patient with cancer, at the patient, nurse and system level.

Lauren C. Mayer is a doctoral-prepared nurse with over 20 years of experience in renowned pediatric healthcare institutions. Her areas of expertise include quantum leadership, clinical care, quality and process improvement, healthcare innovation, and health equity. Mayer has a strong track record of leading diverse teams to design, implement, and sustain impactful enterprisewide evidence-based quality improvement (EBQI) initiatives. She is skilled in leveraging methodologies such as Lean Six Sigma, the model for improvement, and design thinking to drive organizational transformation. Committed to advancing inclusive and high-performing healthcare environments, Mayer brings both strategic vision and practical expertise to every initiative she leads.