Introduction

In Pennsylvania, over 1.4 million residents speak a language other than English at home, including more than 500,000 with limited English proficiency.1 Previous research has found that language barriers between patients and healthcare providers can lead to patient harm, such as longer hospital stays;2–4 greater risk of falls;3–5 and patients being more likely to misunderstand instructions, leading to surgical delays.3 Communication issues resulting from a language barrier can also lead to negative outcomes such as delays in diagnosis and treatment,6 medication errors,7,8 and even death.6 Translation and interpretation services can help to reduce the patient safety risk presented by a language barrier;7,9–11 however, challenges still persist with the methods of translation and interpretation and are important to address to increase patient safety.

While language barriers and patients with limited English proficiency have been well researched, there is a knowledge deficit regarding how communication issues resulting from a language barrier may impact patients in Pennsylvania. We examined the challenges associated with language barriers faced by Pennsylvania patients and healthcare providers and their impact on patient safety. We also included strategies and recommendations to address language barrier–related challenges based on findings described in Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting System (PA-PSRS)[1] reports.

Methods

Data Query

Data for this study were collected from reports in the PA-PSRS database. PA-PSRS reports contain responses to structured fields (e.g., patient age and sex), as well as free-text narrative fields that allow reporters to describe event details in their own words. We queried the PA-PSRS acute care database for reports submitted between January 1, 2024, and December 31, 2024. Reports were included in the initial output if they met one or both of the following criteria:

-

A report that listed a language barrier as a contributing factor in the field “Potential Contributing Factor”

-

A report that included any of the following keywords or phrases in the free-text fields:

-

Language

-

Speaks both

-

Bilingual

-

Multilingual

-

ESL[2]

-

LEP[3]

-

Not proficient in

-

Interpreter/or

-

Translat[4]

-

[Language identifier][5] speaking

-

Speaks [language identifier][5]

-

English

The query produced a total of 869 reports that were manually reviewed for inclusion. Reports met inclusion criteria if they described an actual or potential patient safety risk in which a language barrier was contextually relevant to the event. Reports were excluded if they indicated that the patient declined the use of an interpreter because addressing patient refusal of an interpreter or translated materials could require a multilayered approach and may fall outside the direct control of the facility or healthcare provider and thus are outside the scope of this study.

Variables Coded

We analyzed the reports using data entered by the reporter in both structured and unstructured (free text) fields. We analyzed patient demographics (sex and age), care area group[6], and facility county, which are provided in the structured fields. The information in the free-text fields was coded by the researcher into the variables listed below.

Language. We reviewed the reports to identify the patient’s native language.

Interpretation Challenges. We reviewed the report details to identify a challenge with interpretation (i.e., speaking in a patient’s native language to enable fluid discussion between the patient and healthcare provider).13

-

Interpretation not used

-

Not available: Certified interpreter was not available to healthcare workers.

-

Available, but not offered/not used: Interpreter was available, but provider did not offer or utilize interpreter.

-

Not offered/not used, availability unknown: Interpreter was not offered or utilized, but interpreter availability was unable to be determined by report details.

-

-

Issue with interpretation

-

Equipment or technical issues: Remote interpretation services were hindered by failure to connect, disconnecting, equipment issues/failures, or poor connectivity.

-

Nonprofessional interpretation used: Interpretation was provided by an individual without professional qualifications (e.g., family member).

-

Incorrect or incomplete interpretation: Interpreter did not provide correct information to the patient, or the language used for interpretation was not the language spoken by the patient.

-

Other: Problem with interpretation occurred that did not align with one of the categories listed above.

-

Translation Challenges. We evaluated the reports to identify a challenge with translation (i.e., changing written content such as informed consent documentation and patient education resources into the patient’s native language).13

-

Translation not used

-

Not available: Professionally translated materials were not available to healthcare workers.

-

Not offered/not used, availability unknown: Professionally translated materials were not provided to the patient; however, the availability of these materials was not indicated in the report.

-

-

Issue with translation

- Incorrect or incomplete translation: Translated materials did not provide correct information to the patient, were not translated completely into the patient’s native language (i.e., one or more sections were not translated), or translated materials provided were in a language not spoken by the patient.

-

Unknown: The report described a translation challenge but did not provide specific information about what type of translation issue occurred.

Clinical Process Issues. We examined the reports to determine what impact the language barrier had on the patient care process.

-

Unable to communicate diagnosis and/or treatment or care plan: Healthcare providers were unable to communicate a patient’s diagnosis, plan for treatment or management of a medical issue, or education and instructions (including discharge instructions).

-

Incorrect or inadequate patient history or assessment: Patient assessment and/or collection of a complete or accurate patient history was impeded.

-

Erroneous patient identification: Patient identity was documented incorrectly, or patient was misidentified.

-

Consent miscommunication: Provider attempted to (and thought they did) obtain informed consent, but it was later determined that the patient didn’t understand the procedure when it was explained to them again.

Impact on Patient. We reviewed the reports to identify any adverse outcomes experienced by the patient.

-

Missed or delayed patient care: Access to timely and appropriate treatment, testing, or diagnosis was impeded.

-

Missed appointment or procedure: An appointment or procedure had to be canceled or rescheduled.

-

Fall: Patient experienced an unplanned descent to the floor.

-

Medication safety event: Patient received or self-administered an incorrect medication or dose.

-

Pain: Patient experienced undue pain or prolonged discomfort.

-

Wrong imaging: An incorrect ultrasound or X-ray was performed.

-

Unwanted surgical procedure: A procedure was performed that was not understood and/or wanted by the patient.

-

Inadequate diet or nutrition: Patient missed meals or became undernourished while receiving care at the facility.

-

Hypoglycemia: Patient experienced a hypoglycemic event post-procedure.

Descriptive Data Analysis

We used a retrospective, mixed-methods design with an exploratory sequential approach,14 starting with a focus on the qualitative data, which was then quantified for further analysis. The variables were measured by frequency and assessed using a descriptive data analysis. Descriptive analysis is a quantitative method where phenomena are explored and patterns are identified with the purpose of better understanding and explaining the occurrence of the phenomena.15 This type of analysis is not used to identify causal relationships but is used to characterize the context of the phenomena, point toward possible causal mechanisms, and generate hypotheses.

Results

Patient and Event Characteristics

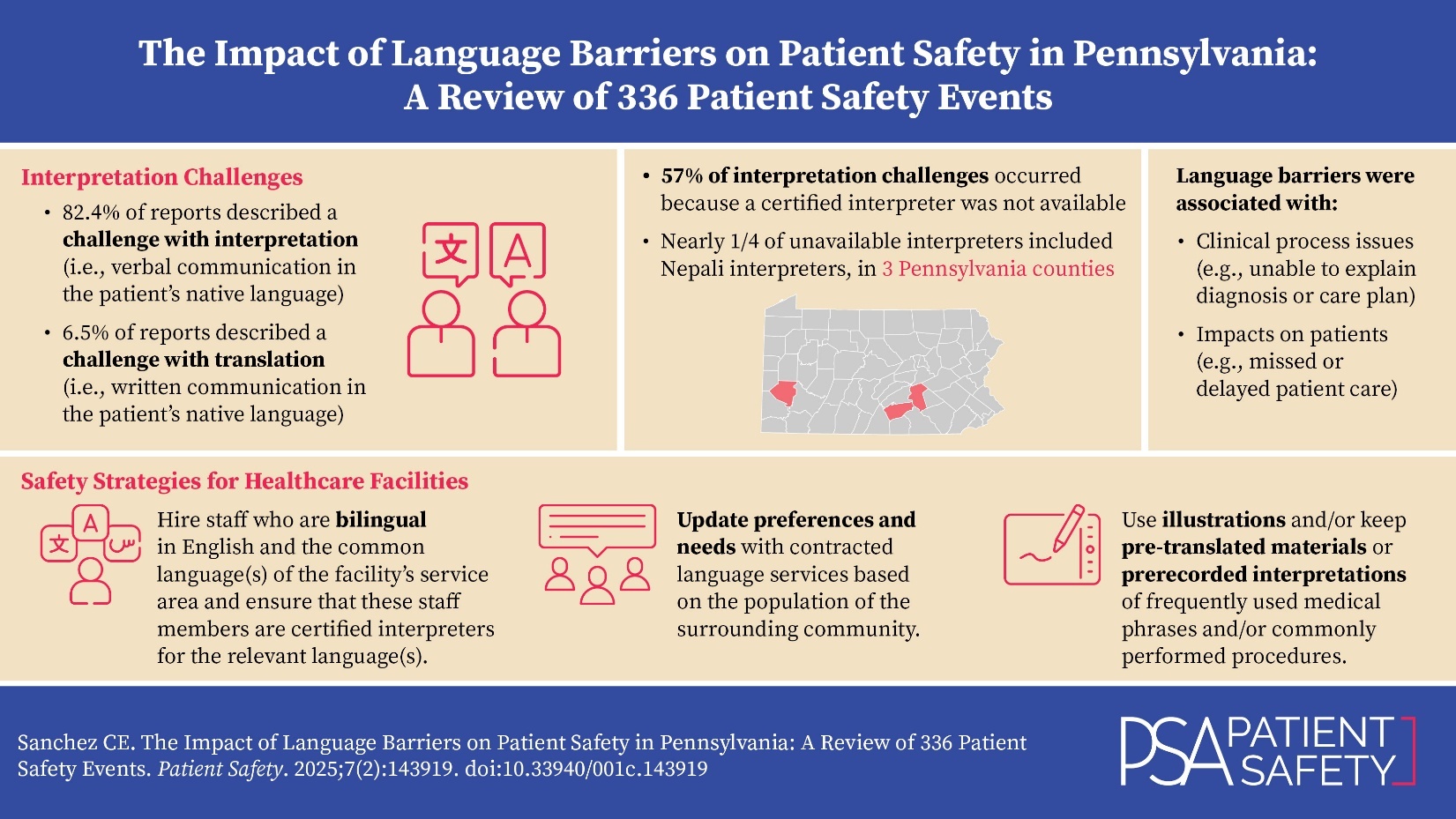

Manual review of reports identified a total of 336 relevant reports from 69 facilities. Sex was reported in 290 reports, with 63.1% (183 of 290) involving a female patient and 36.9% (107 of 290) involving a male patient. The average patient age was 42.3 years, ranging from 1 day to 95 years. The three care area groups with the most frequent reports of language barriers were Emergency (22.6%; 76 of 336), Med/Surg (14.9%; 50 of 336), and Surgical Services (12.2%; 41 of 336), as shown in Figure 1.

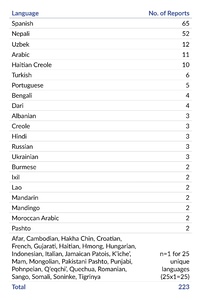

Language

The patient’s native language was included in 223 reports, with a total of 46 languages reported. Two languages, Spanish and Nepali, make up over half (52.5%; 117 of 223) of these reports. The frequency of each language is shown in Table 1.

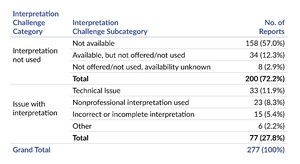

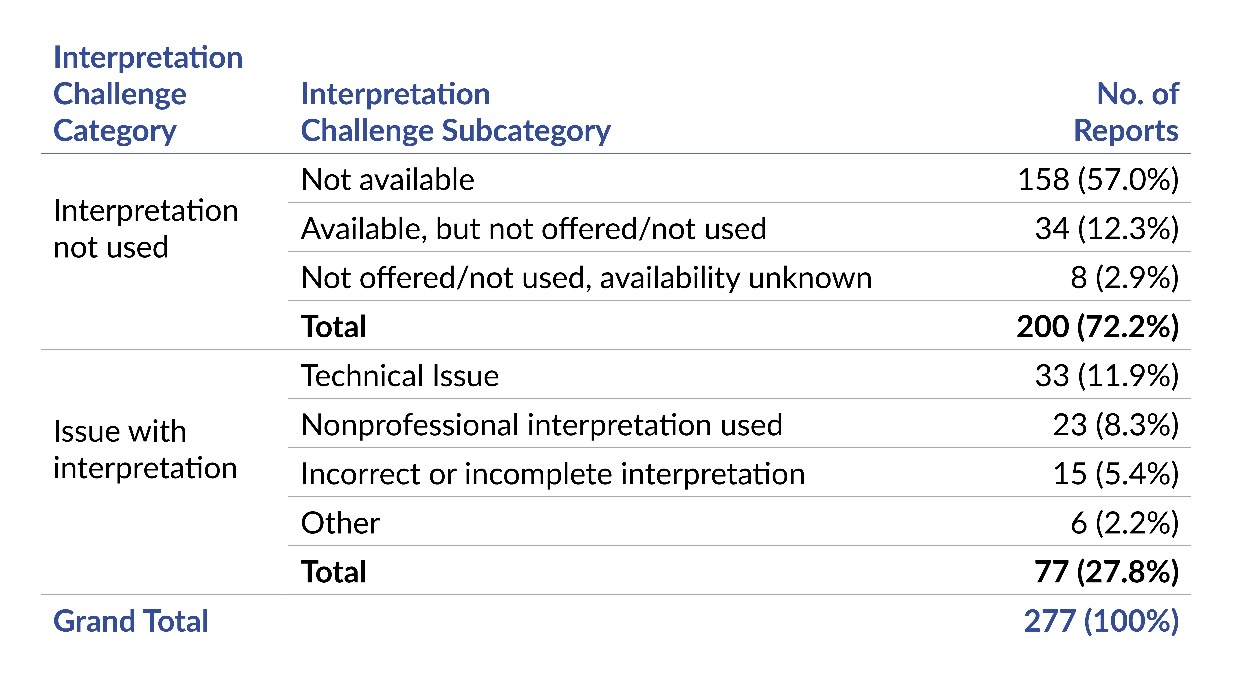

Interpretation Challenges

An interpretation challenge was identified in 82.4% (277 of 336 reports). Details of the interpretation challenges described by the reports are outlined in Table 2. Over half (57.0%; 158 of 277) of reports indicated that interpretation was not used because a certified interpreter was not available.

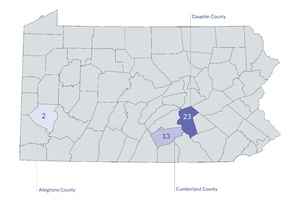

We analyzed the interpretation challenges to determine if there were predominant languages that were associated with these events. Nepali was the most frequently reported language in reports that mentioned interpretation was not available (24.1%; 38 of 158). Furthermore, a large proportion of events where a Nepali interpreter was not available was concentrated in two contiguous Pennsylvania counties, Dauphin and Cumberland, as shown in Figure 2. When interpretation services were available, but not offered/not used, the most frequently reported native language of the patient was Spanish (44.1%; 15 of 34) and these were distributed across 10 counties.

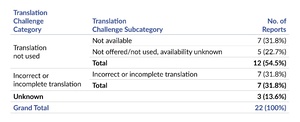

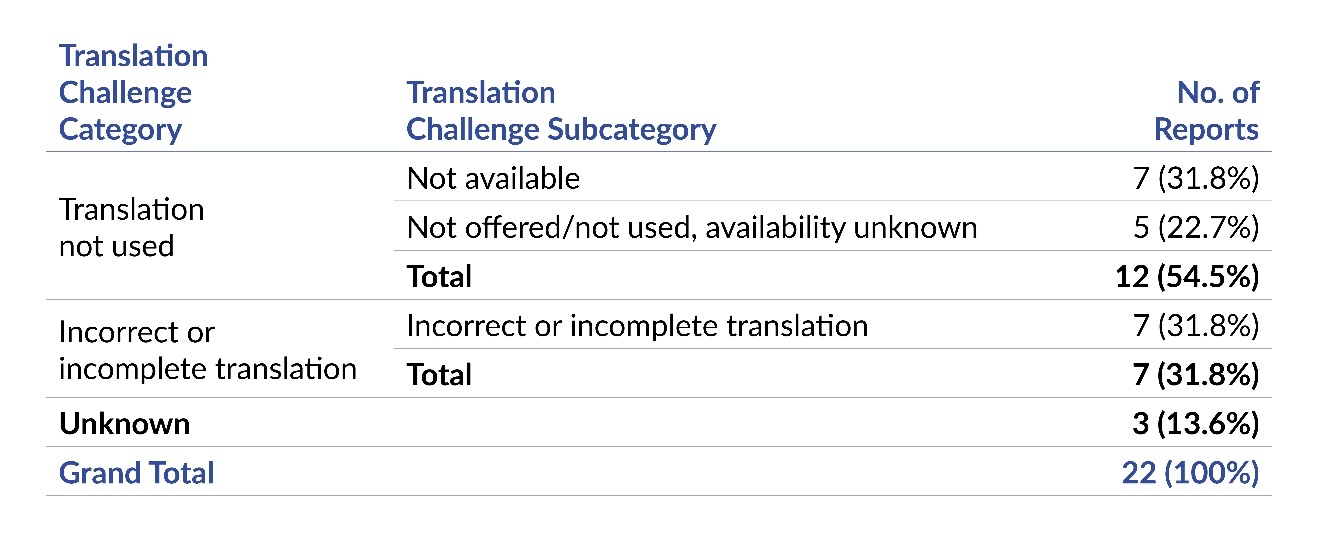

Translation Challenges

Twenty-two of the 336 (6.5%) reports described an issue with translated materials. The most frequently reported issues related to translated materials were that they were not available (31.8%; 7 of 22) or included incorrect or incomplete translation (31.8% 7 of 22), as shown in Table 3.

Clinical Process Issues

A language barrier was associated with clinical process issues in 57 reports. Figure 3 shows that over half (57.9%; 33 of 57) of reports indicated that the language barrier was associated with a provider being unable to communicate diagnosis and/or treatment or care plan.

The reports that described the provider being unable to communicate diagnosis and/or treatment or care plan involve a range of languages and interpretation challenges. These reports include a patient diagnosed with a terminal illness who only had a family member for interpretation; a newly diagnosed child whose mother required interpretation for education, which was unavailable in her native language; interpreter refusal to discuss a sensitive, critical health topic; and patients who were not provided with discharge instructions in their native language.

Impact on Patient

Ninety-five reports described an impact on patients related to the language barrier. The most frequently reported impacts on patients include missed or delayed patient care (55.8%; 53 of 95) and missed appointment or procedure (22.1%; 21 of 95), as shown in Figure 4.

The two occurrences of an unwanted surgical procedure involved patients who spoke a Spanish dialect and did not understand the circumcision procedure when it was explained to them for their newborns. After the procedures were performed, both mothers expressed they did not know what was going to be happening to their babies, and one explicitly said that she had not wanted the procedure performed. A Spanish interpreter was utilized to explain circumcision procedure; however, it is likely that the language barrier was unable to be overcome due to the dialects spoken by the mothers.

Discussion

Our analysis identified interpretation and translation challenges that facilities in Pennsylvania encounter and how they can impact the clinical process, patient experiences, and patient safety. There are a number of regulations and governing bodies that require the provision of certified medical interpreters to patients with low English proficiency (LEP), including The Joint Commission16,17 and the prohibition of discrimination based on an individual’s national origin by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.18 Despite this, and even with facility policies regarding the use and availability of medical interpreters, our data show that challenges still exist when dealing with patients who do not speak English or have a preferred language other than English.

Consistent with previous studies,2,4,5,7,19 we found that language barriers can contribute to patient safety risks in a variety of clinical settings5,7,19 (e.g., emergency department) and can involve a range of languages.2,4,5 Similar to previous research,3–5,7,8 we found that language barriers were associated with patient safety events such as falls,3–5 delayed or canceled procedures,3 and medication errors.5,7,8 Additionally, by identifying details of the events reported to PA-PSRS such as the patient’s native language, geographical concentration of specific language/interpretation deficiencies, and impacts on the clinical process and patient experiences, we were able to examine language barrier challenges that are encountered by Pennsylvania facilities. Based on these results as well as information available from the literature,2–8 we have provided suggestions to help Pennsylvania facilities understand current concerns about language barriers and overcome them to increase patient safety.

While there are multiple options for overcoming a language barrier, including the use of in-person certified medical interpreters,9,11 video remote interpretation (VRI) services,20 and other interpretation and translation service providers (e.g., phone interpretation),21 the results from this study highlight that even when these services are provided, language barriers can be difficult to overcome. This study found that the provision or access to language services did not guarantee availability of an interpreter, and, in some instances, an available interpreter was not able to correctly interpret or refused to interpret certain health conditions.

Over half of reports that described an interpretation challenge indicated an interpreter was not available. Nearly one quarter of these reports involved Nepali-speaking patients, with a large proportion concentrated in two contiguous Pennsylvania counties, Dauphin and Cumberland. These findings highlight the importance of understanding population diversity to better anticipate interpretation and translation needs. Upon further exploration, there is a large community of Nepali-speaking Bhutanese individuals in this area of the state.22 The identification of this availability issue and population information suggests that knowledge of population diversity and available language services may be able to help facilities improve access to interpreters when necessary. Existing guidance about how to navigate healthcare encounters that involve a language barrier include recommendations such as having knowledge about the facilities’ surrounding population.16,23 This recommendation should be implemented along with others such as those listed below to ensure sufficient access.

-

Hire staff who are bilingual in English and the common language(s) of the facility’s service area and ensure that these staff members are certified interpreters for the relevant language(s).24 Language and interpretation skills should be tested and validated regularly.24

-

Document patients’ preferred language in their medical record.24

-

Inquire not only about the availability of certain language interpreters by a language service provider, but how many interpreters are available at any given time for languages that are prominent in a facility’s surrounding population.

-

Continue to update preferences and needs with contracted language services based on the population of the surrounding community.

-

Collaborate with community groups to educate community members about the opportunity to become certified medical interpreters to help increase the availability of in-person interpreters and/or translated materials.

Facilities can also identify high-risk scenarios24 (e.g., medication reconciliation, patient discharge, informed consent, emergency department encounters, and surgical procedures) and implement policies such as requiring the use of qualified interpreters, providing materials that are translated to the patient’s preferred language, and using the teach-back method to confirm patient understanding.24 The use of the teach-back method can be combined with utilizing visual aids to help with patient education and consent for procedures.

The use of visual aids16,24 (e.g., pictures and/or diagrams) may be especially helpful in cases such as the reports describing the misunderstanding of circumcision procedures. In both cases, the mothers spoke a specific Spanish dialect. As dialects can be rare, finding a certified interpreter may be challenging, and the use of visual representations of a procedure may help to ensure the patient understands the procedure that is being explained to them.

While certified interpreters should be the first choice, some language interpretation or translation may be better than nothing in situations where certified interpreters are not available. Facilities may also benefit from establishing a backup plan for language services contracts in the event of a technical or availability issue. For example, facilities can keep pre-translated materials or prerecorded interpretations25 of frequently used medical phrases on hand. Other examples of such backups include phone apps (such as Google Translate) and free or low-cost online services like Tarjimly, which has both free and paid options and is staffed by volunteers.

Limitations

The quality of information provided in the free-text fields of PA-PSRS reports varies, and some reports contain more detailed information than others. Our analysis is limited by the information provided. In addition, despite mandatory reporting laws in Pennsylvania, it is possible that the events reported to PA-PSRS may not represent all occurrences of a language barrier–related patient safety event. Additionally, the reports reviewed in this analysis included languages that were not in the list of language identifiers used in the data query. It is possible that some reports were omitted if they did not include one of the searched-for language identifiers nor one of the other keywords searched. We acknowledge that some of the recommendations for effective communication with LEP patients may be limited by factors such as cost, feasibility of implementation, and the education level and medical knowledge of community members. Furthermore, this study was not able to address cultural nuances that may accompany language barriers, as the information in the reports was not sufficient to examine culturally based influences on language barriers and patient safety.

Conclusion

Previous literature2–8 has identified the risks to patient safety that can be introduced when a language barrier between the patient and provider exists. This study was able to leverage patient safety events in the PA-PSRS database to provide insights about the types of interpretation and translation challenges experienced, as well as how these impact the clinical process and patients. Furthermore, we were able to identify the challenges associated with a language barrier that Pennsylvania providers and patients experience. Implementing strategies that are additive to the availability of a language service to overcome language barriers can help reduce the impact of a language barrier on patient safety.

Notes

This analysis was exempted from review by the Advarra Institutional Review Board.

Data used in this study cannot be made public due to their confidential nature, as outlined in the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error (MCARE) Act (Pennsylvania Act 13 of 2002).

Disclosure

The author declares that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

PA-PSRS is a secure, web-based system through which Pennsylvania hospitals, ambulatory surgical facilities, abortion facilities, and birthing centers submit reports of patient safety–related incidents and serious events in accordance with mandatory reporting laws outlined in the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error (MCARE) Act (Act 13 of 2002).12 All reports submitted through PA-PSRS are confidential and no information about individual facilities or providers is made public.

ESL = English as a Second Language

LEP = Limited English Proficiency

“Translat” was used to search for “translate,” “translated,” “translation,” “translating,” and any other conjugation of the word that may have been included in the free-text fields of the event report.

Language identifier includes the following languages: Amharic, Arabic, Armenian, Bengali, Cajun, Cantonese, Chinese, Croatian, Dari, Dutch, English, Farsi, Filipino, French, German, Greek, Gujarati, Haitian, Hawaiian, Hebrew, Hindi, Hindu, Hmong, Igbo, Ilocano, Italian, Japanese, Kannada, Khmer, Korean, Lao, Malayalam, Mandarin, Marathi, Navajo, Nepali, PA Dutch, Pennsylvania Dutch, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi, Russian, Samoan, Serbian, Serbo-Croatian, Slavic, Spanish, Swahili, Tagalog, Tamil, Telugu, Thai, Twi, Ukrainian, Urdu, Vietnamese, Western African, Yiddish, Yoruba

Within PA-PSRS, the event reporter chooses among 168 care areas to indicate the location where an event occurred. To simplify our analysis, we sorted each of the care areas into 23 higher-level care area groups.