Introduction

Insulin is an endogenous peptide hormone secreted by the pancreas.1,2 As a medication, it is used to treat diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemic crises, such as diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state; to control stress-induced hyperglycemia; and to lower serum potassium levels as an adjunct therapy for hyperkalemia in the acute care setting.2 Despite its several lifesaving uses by millions of people around the world,3,4 insulin is widely recognized as a complex and dangerous medication.2,5–11

Insulin has been associated with more medication errors than any other medication type or class.12–14 Of particular concern are dosing errors, which carry a substantial risk of patient harm, including death.13,15–18 One of the challenges in measuring a dose of insulin involves insulin’s unique measurement in units rather than milliliters (mL). The Patient Safety Authority has previously reported accidental overdoses of insulin resulting from confusion between these measurements,6,19–22 often when tuberculin syringes (marked in mL) were used instead of insulin syringes (marked in units).19,20,23,24 Other published literature has also reported the use of tuberculin (1 mL), 3-mL, and 10-mL syringes to administer insulin leading to overdoses of up to a hundredfold.11,15,17,22,25–27

When a syringe is used to prepare and administer insulin, there is an added complexity associated with multiple routes of administration.1,28 While subcutaneous administration is frequently used for blood glucose management, insulin can also be given by the intravenous route to lower serum potassium levels17,20,21 or lower blood glucose levels in some patients.29,30 Prior to the availability of insulin luer-lock syringes, providers were limited to using non-insulin syringes for intravenous administration.17 This has created various workarounds for administering intravenous insulin which have led to medication errors.17

The potential for wrong dose errors involving insulin is further compounded by the variability in hospital formularies and protocols for preparation, dispensing, administration, and storage practices.11,17,21,22,31,32 Some facilities centralize insulin preparation in the pharmacy, while others store various insulin products in patient care areas for preparation by nurses.32 The lack of uniform practice, combined with the historical unavailability of insulin syringes designed for intravenous administration, creates vulnerability within the medication-use system and increases the risk of medication errors leading to patient harm.

This study aims to examine issues related to the use or selection of syringes during insulin preparation, dispensing, or administration in acute care settings that may lead to dosing errors or discrepancies. The insights generated from this study will inform the development of strategies to help healthcare providers prevent syringe-related insulin errors and mitigate the risk of patient harm.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective mixed-methods study using an exploratory sequential design33 to investigate insulin medication errors related to syringe use. The data source used in the study was the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting System (PA-PSRS)[1], a statewide repository for patient safety event reports.34

We queried the PA-PSRS acute care database for reports submitted between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2024. We targeted reports categorized as “Medication Error” across all harm scores in which the prescribed medication was “insulin” or any generic or brand insulin product that was available on the market during the queried time frame.35

A focused query of the PA-PSRS fields was performed to identify relevant reports involving issues related to insulin syringes and potential for wrong dose errors. To be considered for further review, a report had to satisfy at least one of the following criteria:

-

The free-text fields contained the following keywords: “wrong syringe” or “syringe” paired with “cc,” “ml,” “tb,” “tuberculin,” or “instead.”

-

The calculated ratio of Dose Administered to Dose Intended was greater than or equal to 10.

-

The Dose Administered field contained the keywords “ml” or “cc.”

After retrieving reports through this query, we developed an operational definition of syringe-related issues to guide report inclusion. Syringe-related issues were defined as the use or selection of a syringe during insulin preparation, dispensing, or administration that contributed to, or had the potential to contribute to, a dosing error or discrepancy. Reports were included if they involved U-100 insulin and met this definition under any of the following conditions:

-

The report explicitly mentioned the use of a wrong syringe (i.e., a syringe the reporter deemed inappropriate or against the facility’s protocol).

-

The report did not explicitly mention the use of a wrong syringe, but one of the following proxy indicators was present:

-

A single insulin dose exceeding 100 units was prepared or administered, suggesting the use of a non-insulin syringe, as U-100 insulin syringes typically have a maximum capacity of 100 units.36,37

-

An insulin dose of 100 units or less was prepared or administered, with the volume described in “ml” or “cc” and representing a tenfold multiple of the intended amount, indicating the use of a syringe with millimeter or cubic centimeter markings rather than a U-100 insulin syringe.

-

Reports were excluded if the insulin error or discrepancy originated from issues unrelated to syringe use, such as wrong patient, wrong drug, wrong concentration, or equipment malfunction. Additionally, reports that described incorrect dosing without clear or inferred syringe-related issues were excluded. Reports involving infants who required the use of tuberculin syringe instead of insulin syringe to deliver diluted solutions of insulin were also excluded.

Variables Coded

The PA-PSRS database contains both structured and unstructured (i.e., free text) fields. The structured fields, which are completed by the reporter at the time of submission, capture data such as facility type, care area type[2], event classification (incident[3] or serious event[4]),34 and medication-specific details (e.g., name, dose, and route for intended and administered medications). Two researchers reviewed and coded data in the structured and unstructured fields. Structured data were standardized during this process; for example, insulin names were converted to their generic forms. Narrative details from unstructured fields were used to verify, clarify, and supplement structured data, as well as resolve ambiguities related to the reports. This dual review process also supported overall coding accuracy.

The following variables were coded for analysis.

Near Miss. Reports were coded as near misses if the event did not reach the patient due to chance or active intervention. If a near miss report included information about the dose that would have been administered, this value was included in the analysis as an “administered dose.”

Clinical Indication. Reports containing sufficient detail were coded for clinical indication, defined as the underlying medical condition or reason for which insulin was prescribed.

-

Glucose management was coded when a report described the use of insulin to lower or manage blood glucose levels.

-

Hyperkalemia was coded when a report described the use of insulin to lower serum potassium levels.

Wrong Dose Ratio. Reports containing sufficient detail were coded for wrong dose ratio, defined as the degree of deviation from the intended dose. When both intended and administered doses were reported, the ratio was calculated from these values; when either value was missing, the ratio was extracted directly from the free-text description if the reporter specified the degree of deviation.

Syringe Size. Reports containing sufficient detail were coded for syringe size, defined as the volume of the non-insulin syringe involved in the event. Syringes were coded as 1 mL if the report specified the use of a tuberculin or other non-insulin 1-mL syringe instead of an insulin syringe. Throughout this manuscript, “1-mL syringe” refers specifically to non-insulin 1-mL syringes, including tuberculin syringes. All non-insulin syringe sizes were coded; for this analysis, only 1-mL syringes are highlighted.

Contributing Factor. Reports containing sufficient detail were reviewed for contributing factors, defined as preventable elements or conditions that increased the likelihood of the medication event. Although a contributing factor may not have been coded in a given report, this does not imply one was absent, only that one was not clearly described. Three contributing factors were identified:

-

Storage was coded if the syringe involved in the event was improperly stored in a bin intended for insulin syringes or was stored in close proximity to insulin syringes.

-

Similar Packaging or Cap Color was coded if the syringe involved in the event had a cap color or external packaging that appeared similar to that of an insulin syringe.

-

Trainee was coded if the reporter mentioned that the provider involved was a trainee, an orientee, or a new practitioner with limited experience.

Additional contextual details were also coded, including the location of insulin preparation, facility-specific formulary or protocols related to insulin syringes, and whether the reporter noted that a luer-lock insulin syringe should or could have been used to prevent the event.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data analysis was performed using content analysis38–41 and the framework method.33,42,43 The variables used in this study were generated through a combined deductive and inductive approach, by using the existing taxonomy within PA-PSRS in addition to identifying emerging themes and details from the collected data. The variables were quantified for frequency and processed through descriptive analysis. This approach aimed to characterize phenomena by identifying meaningful information and facilitating data visualization.44 Descriptive analysis does not establish causal relationships but rather clarifies the environment in which the phenomena occur, suggests potential underlying factors, and generates hypotheses for future investigations.44

Results

The study included 74 reports across 47 facilities. Most facilities (32 of 47, 68.1%) submitted a single report, while the two facilities with the highest frequency each submitted five reports.

Event Classification

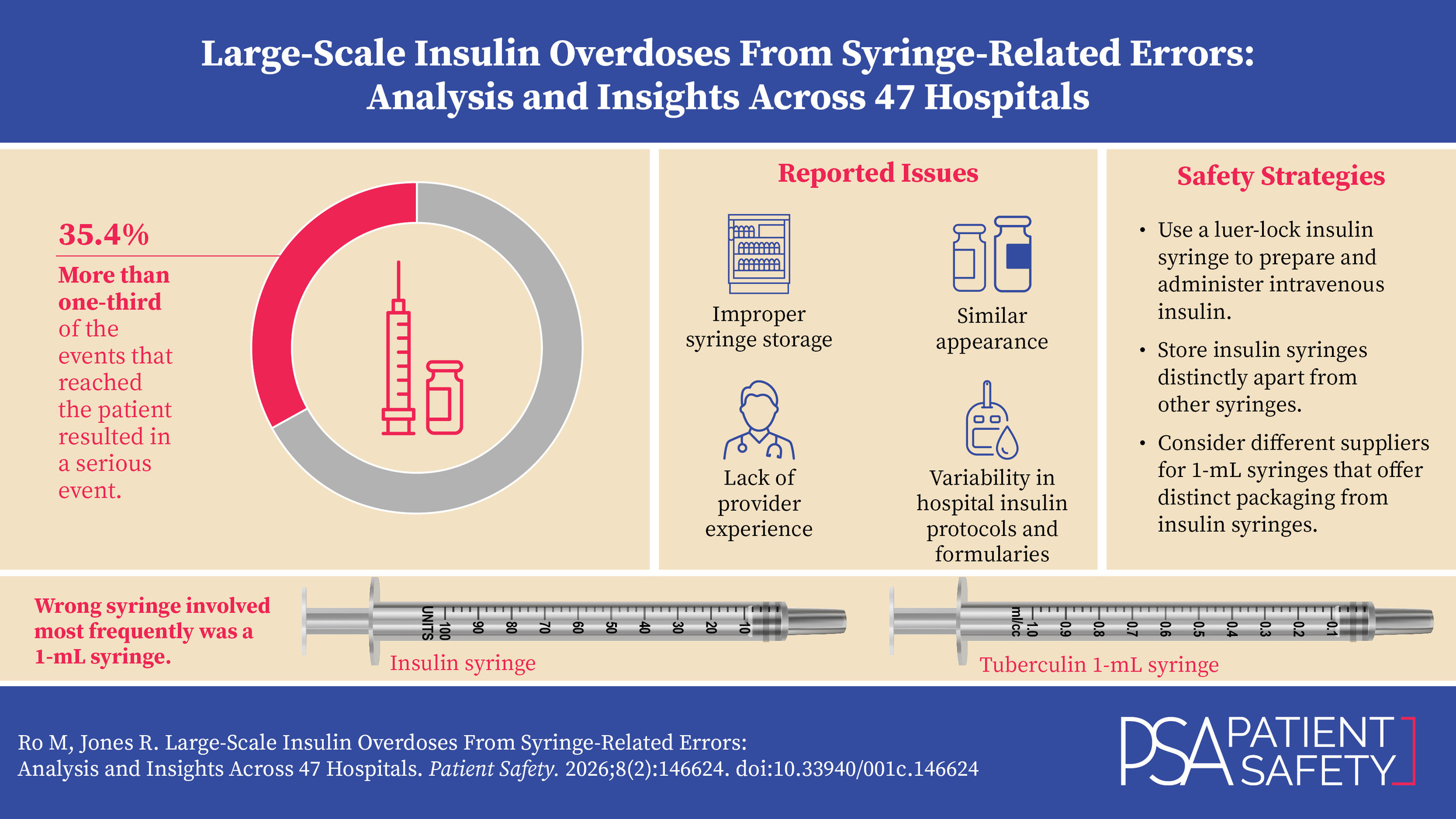

Of the 74 total reports, 57 (77.0%) were classified as incidents, including 26 near misses that represented 35.1% of all reports. Serious events, which resulted in patient injury that required additional healthcare services,34 accounted for nearly one-quarter of all reports (17 of 74, 23.0%) and over one-third of reports describing an event that reached the patient (17 of 48, 35.4%).

Of the 26 near misses, 15 (57.7%) involved insulin doses prepared and dispensed by the pharmacy. These included doses dispensed in an incorrect syringe or in a syringe type unanticipated by the receiving nurse. Some of these syringes contained dilutions whose dose could not be verified by visual inspection.

Intended Route of Administration, Insulin Product, and Clinical Indication

Of the 74 total reports, 43 (58.1%) involved an intended subcutaneous route of administration, while 31 (41.9%) specified intravenous administration. The insulin product involved was specified in 70 reports. Insulin regular was most frequently reported (31 of 70, 44.3%), followed by insulin lispro (16 of 70, 22.9%) and insulin aspart (12 of 70, 17.1%). While all of the insulin products were involved with subcutaneous use, only insulin regular and insulin aspart were associated with intravenous use. Figure 1 shows the frequency of reports by intended route of administration and insulin product.

Of the 61 reports that contained information regarding clinical indication for insulin use, 50 (82.0%) were for glucose management and 11 (18.0%) were for hyperkalemia. When stratified by intended route of administration, nearly all reports involving subcutaneous insulin (42 of 43, 97.7%) were for glucose management. In contrast, intravenous insulin had a broader distribution: out of 18 reports, 10 (55.6%) were for hyperkalemia and 8 (44.4%) were for glucose management.

Wrong Dose Ratio

Of the 74 total reports, 70 provided an intended dose and 56 provided an administered dose. The median intended dose was 5.5 units for subcutaneous insulin and 10 units for intravenous insulin. For administered doses, the median was 100 units for both subcutaneous and intravenous insulin. The minimum intended dose was 0.75 units and the maximum was 45 units. Administered doses ranged from a minimum of 7.5 units to a maximum of 1,800 units.

Among the reports, 55 contained sufficient information to calculate the wrong dose ratio (Table 1). A ratio of 1 indicates that the intended and administered doses matched, though risk was still present. All 5 reports with a ratio of 1 were near misses involving pharmacy-prepared insulin in incorrect or unexpected syringes, causing confusion and potential for error. Tenfold overdoses were most frequent, identified in 31 reports (56.4%), followed by hundredfold overdoses in 11 reports (20.0%), 10 of which reached the patient. Among all wrong dose errors that reached the patient, 97.7% (43 of 44) involved a tenfold or greater overdose.

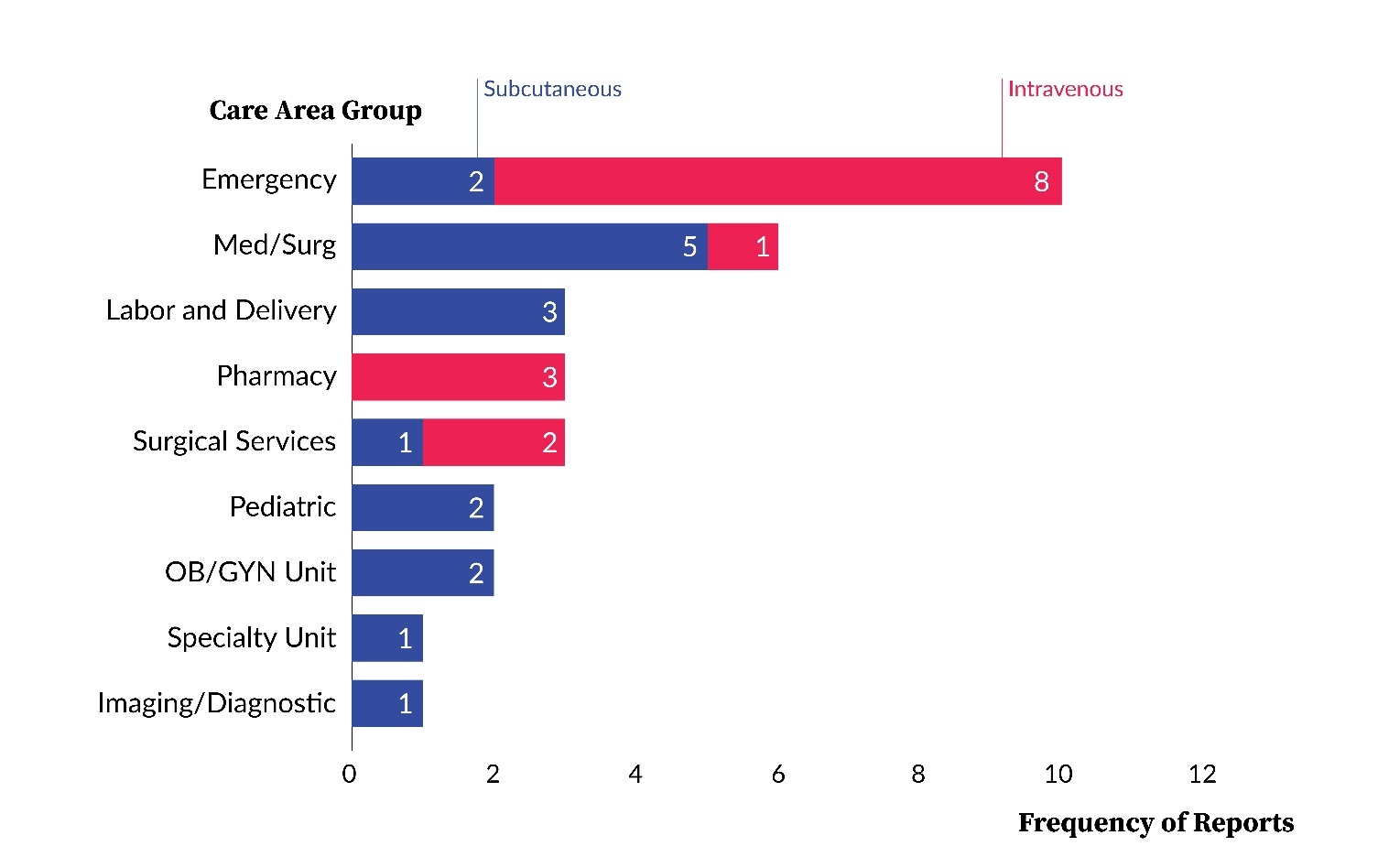

Care Area Group

Over half of the total reports were associated with one of two care area groups: the medical/surgical unit (21 of 74, 28.4%) or the emergency department (17 of 74, 23.0%). These were followed by surgical services (7 of 74, 9.5%), intensive care unit (6 of 74, 8.1%), and pharmacy (6 of 74, 8.1%).

In medical/surgical units, the majority of reports (14 of 21, 66.7%) involved subcutaneous administration. By comparison, most reports from the emergency department (11 of 17, 64.7%) involved intravenous administration. The distribution of reports by care area group and intended route of administration is presented in Figure 2.

As shown in Figure 3, across all care area groups and reports with sufficient data to calculate the wrong dose ratio, the emergency department had the highest number of tenfold overdoses (9 reports). The intensive care unit had the highest proportion of hundredfold overdoses (4 of 5, 80.0%), while medical/surgical units had a broader distribution, with tenfold overdoses in 7 of 16 reports (43.8%) and hundredfold overdoses in 4 of 16 reports (25.0%).

Syringe Details

Of the 42 reports containing information regarding syringe size, 31 (73.8%) involved the use of a 1-mL syringe. Among reports that documented an overdose with the use of a 1-mL syringe, nearly all (20 of 21, 95.2%) were associated with a tenfold overdose. Figure 4 shows the distribution of 1-mL syringe use by care area group and intended route of administration. The emergency department had the highest number of reports referencing 1-mL syringe use, 80.0% of which were associated with the intravenous route.

Additionally, in five reports that involved intravenous insulin, the reporter specifically mentioned that luer-lock syringes should or may have been used to prevent the event, or that the facility is switching to luer-lock syringes as a result of the event. One report detailed a hundredfold overdose with 1,000 units of insulin regular administered by a newly hired nurse. In response to this event, the facility implemented two-person verification for insulin boluses to treat hyperkalemia and adopted luer-lock syringes to prevent future errors.

Contributing Factors

Of the 74 total reports, 17 identified one or more contributing factors, with 3 reports specifying two distinct factors. Storage issues were the most common, identified in 9 reports, followed by trainee involvement in 7 reports. In one trainee-related report, the individual noted, “I thought that the number of units correlated to mL.” This event was associated with a 1,000-unit administration of insulin aspart to treat hyperkalemia instead of the intended 10 units. Lastly, 4 reports were attributed to similar packaging or cap color.

Variation in Insulin Protocols

The reports also revealed patterns in insulin vial volumes dispensed from automated cabinets, including 3 serious events in which nurses used 10-mL vials for preparation and administration on patient care units. In another serious event, a nurse prepared and administered an entire 3-mL vial of insulin aspart for treatment of hyperkalemia instead of the ordered 10 units, resulting in intensive care unit (ICU) transfer and multiple medical interventions, including hemodialysis.

Additionally, 3 reports demonstrated how facilities’ predominant use of insulin pens can create risks when nurses must switch to vials and syringes. In one case, a nurse resorted to vial and syringe after the patient’s pen could not be located, resulting in a hundredfold overdose. Another report involved a premixed insulin that was among the few formulary options not available in pen form, and it was the nurse’s first time using a syringe to administer insulin. This event resulted in the administration of the entirety of the 10-mL vial (1,000 units) of insulin instead of the ordered 24 units.

Discussion

Our study is the first investigation into syringe-related issues associated with the preparation, dispensing, and/or administration of insulin using a large database of patient safety event reports. While existing literature includes individual case reports of syringe-related overdoses15,19,20,22,23,25,26 and broader analyses of insulin errors and interventions over the years,5,6,8,10,13,18,21,28,45,46 our study provides insight into 74 reports across 47 acute care facilities in Pennsylvania involving this specific scope of medication error.

One notable finding from our study is the magnitude of overdoses resulting from syringe-related issues. More than 97% of wrong dose errors that reached the patient resulted in an overdose of tenfold or greater. We identified 11 reports with a wrong dose ratio of 100, 10 of which reached the patient. One report involved a provider attempting to give 1,800 units of insulin subcutaneously instead of 18 units. This event highlights dual safety concerns: The provider appeared unaware of the magnitude of overdose and nearly administered this potentially lethal dose via the subcutaneous route.

Of reports specifying syringe volume, 73.8% involved a 1-mL syringe and 95.2% of overdoses with these syringes were exactly tenfold. Several reports described providers who intended to administer 10 units of intravenous insulin but inadvertently administered 100 units (equivalent to 1-mL volume) using a 1-mL syringe. This association between the use of 1-mL syringes and tenfold insulin overdoses has been previously identified in advisories issued by the Patient Safety Authority.19–21,23

We also observed distinct patterns across different care areas. Reports originating from emergency departments showed the highest frequency of intravenous insulin administration, 1-mL syringe use, and tenfold overdoses. Although medical/surgical units had the highest total number of reports, intensive care units reported the largest proportion of hundredfold overdoses.

Finally, our analysis revealed variability in hospital protocols surrounding insulin preparation, dispensing, and administration. While some facilities described dispensing insulin vials directly to patient care areas for nurse preparation, others utilize centralized pharmacy preparation. Each approach introduces distinct safety risks, with direct dispensing increasing the likelihood of bedside preparation errors and pharmacy preparation potentially causing confusion about dose concentration or syringe type. Furthermore, the increasing use of insulin pens presents its own complexities; some errors involved providers who were more accustomed to using pens and less familiar with preparing insulin from vials and syringes. Protocols for insulin use in hyperkalemia also vary. The lack of a universal, standardized approach to insulin management across healthcare facilities likely contributes to the persistence of medication errors involving insulin.

Safety Strategies

Table 2 outlines various strategies that healthcare providers and systems can implement to enhance safety related to preparation, dispensing, and administration of insulin by syringe. Given the variability in institutional workflows, processes, and available resources, facilities should identify and adopt strategies that align with their specific operational environments. Ongoing surveillance of insulin-related errors and development of achievable improvement goals will support sustained progress in patient safety.

Limitations

Our study, while offering novel insights, is subject to several limitations inherent to event reporting. The level of detail provided in the event descriptions is variable and dependent on the reporter. Additionally, relevant events may have been missed if the reporting facility did not classify them as “Medication Error.” Furthermore, the aggregated nature of PA-PSRS data presents a broad overview rather than site-specific conclusions. Therefore, the results in this study should not be directly applied to individual facilities but rather should serve as a basis for further site-specific investigations.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of preventing syringe-related issues associated with insulin preparation, dispensing, and administration within acute care settings. Our findings underscore that syringe-related insulin overdoses, particularly tenfold and hundredfold, are not isolated events but occur across a variety of care area groups and in numerous hospitals across the state. The use of non-insulin 1-mL syringes creates potential for wrong dose errors, especially tenfold overdoses. Contributing factors such as improper syringe storage, similar packaging, and provider inexperience were observed, as were systemic vulnerabilities in insulin preparation, dispensing, and administration workflows. We encourage readers to address these multifaceted issues by evaluating their own insulin protocols and implementing multilayered strategies that enhance safety for patients receiving insulin.

Note

This analysis was exempted from review by the Advarra Institutional Review Board.

Data used in this study cannot be made public due to their confidential nature, as outlined in the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error (MCARE) Act (Pennsylvania Act 13 of 2002).

Artificial intelligence (GPT-5) was used only to improve sentence clarity. No AI was used for data analysis, interpretation, or generation of original content. The authors take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

About the Authors

Myungsun (Sunny) Ro (mro@pa.gov) is a research scientist on the Data Science & Research team at the Patient Safety Authority (PSA). Her responsibilities include analyzing and synthesizing data from various sources to identify opportunities to improve patient safety, as well as writing scientific articles for publication in the PSA’s peer-reviewed journal, Patient Safety.

Rebecca Jones, director of Data Science & Research for the Patient Safety Authority, leads a multidisciplinary team advancing patient safety through research that informs improvements in healthcare systems and delivers insights that bridge the gap between evidence and real-world practice. A registered nurse with a Master of Business Administration in healthcare management and certifications in patient safety, human factors, and risk management, she brings clinical experience, analytical expertise, and systems thinking to complex challenges. She has authored more than 40 peer-reviewed publications and contributed to national patient safety efforts with organizations such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the National Quality Forum, and the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine.

PA-PSRS is a secure, web-based system through which Pennsylvania hospitals, ambulatory surgical facilities, abortion facilities, and birthing centers submit reports of patient safety–related incidents and serious events in accordance with mandatory reporting laws outlined in the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error (MCARE) Act (Act 13 of 2002). All reports submitted through PA-PSRS are confidential and no information about individual facilities or providers is made public.

Within the PA-PSRS acute care database, there are 168 care areas for facilities to use to identify where events occur. Each of these care areas is then placed into one of 23 higher-level care area groups.

An incident is defined as “an event, occurrence or situation involving the clinical care of a patient in a medical facility which could have injured the patient but did not either cause an unanticipated injury or require the delivery of additional health care services to the patient.”

A serious event is defined as “an event, occurrence or situation involving the clinical care of a patient in a medical facility that results in death or compromises patient safety and results in an unanticipated injury requiring the delivery of additional health care services to the patient.”

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)