Introduction

Sepsis is an emergency that significantly increases mortality risks for patients of all ages.1 Therefore, early identification and treatment are essential in the emergency room setting to prevent further sepsis-related morbidity and mortality.2

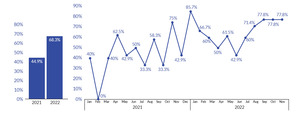

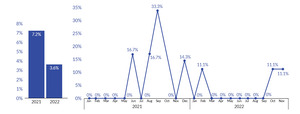

At Allegheny Health Network (AHN) Grove City Hospital in 2021, adherence to the best practice treatment for sepsis management was low at 44.9% year-to-date compliance. In 2021, the hospital sepsis mortality rate was 7.2%. Overall compliance with the best practice treatment was below national and state benchmarks of 55% for Pennsylvania and 57% nationally.3 Sepsis was identified as a key driver contributing to the hospital’s mortality rate in 2021. In October 2021, a retrospective review of patients diagnosed with sepsis in the emergency room showed that only 42% of patients were screened for sepsis in triage.

Available Knowledge and Rationale

Sepsis results from infection and, if untreated, can lead to organ dysfunction and death. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) define interventions to treat sepsis, including early antibiotic administration, fluid resuscitation, and medication to support a patient’s blood pressure.4 However, implementing these lifesaving interventions is contingent on the early detection of sepsis. Early detection significantly influences the likelihood of survival from sepsis, with previous research demonstrating an increase in mortality for every one-hour delay in sepsis recognition and treatment. Early detection can be achieved by recognizing the known sepsis criteria collected through physical patient assessments and lab testing.4 In addition, nurse-led sepsis screening has aided in early identification to start timely treatment interventions.5

Though screening tools are known to facilitate the early detection of sepsis, to be helpful, they must be accessible and visible. Previous human factors engineering literature has shown the importance of the designing process that works for frontline users.6 Additionally, embedding tools such as screening tools into workflows helps minimize human errors and variation between users with varying skill sets. This approach designs a workflow rather than relying on training.6 Strategies to minimize variation in sepsis screening are of utmost importance. Registered nurses’ (RNs) knowledge of sepsis varies based on several factors, including education, work unit, and years of service. Applying a human factors intervention can assist in hardwiring workflows despite any variation of knowledge or care setting, which is particularly imperative in efforts to improve the timely detection of sepsis.

Rationale

Observations and interviews were conducted with frontline employees and management. The frontline observations revealed variations in nurse-led sepsis screening. The observations and interviews also found decreased staff engagement in sepsis tools and processes in the electronic medical record (EMR). In interviews, one root cause identified for decreased engagement was a transition in the hospital to a different EMR system. After transitioning to the new EMR system, the sepsis screening criteria were hidden and calculated with analytics. It was concluded that the change to the new EMR system fragmented sepsis screening criteria and information within the workflow and created a challenge for accurate, reliable screening. We hypothesized that centralizing sepsis screening criteria in one place to ensure congruence with the existing workflow would lead to increased sepsis screening and more timely sepsis detection.

Specific Aims

The project was intended to improve compliance with sepsis best practice treatment and ultimately decrease the overall sepsis mortality rate. The project aimed to increase the sepsis best practice treatment compliance from baseline (44.9% in 2021) to 50% over the next year by implementing human factor interventions. Additional process measures aimed to increase triage screening by 20% and to increase physician treatment order set use by 10% from the baseline in the next calendar year of 2022.

Objectives

The key objective of this project was to be more proactive in identifying and managing potentially septic patients by increasing awareness of sepsis criteria triggers in triage rather than reacting when septic patients begin to deteriorate. In addition, we aimed to apply human factors–based best practices to facilitate sepsis screening and early treatment.

Context

AHN Grove City Hospital is a small community hospital in Grove City, Pennsylvania, with 67 licensed beds and is part of a hospital network consisting of nine hospitals in Pennsylvania and one in New York. AHN acquired Grove City Hospital in December 2020. The electronic medical system changed from The T System to Epic during the transition period in February 2021.

This quality improvement project occurred in the Emergency Department (ED), an eight-bed unit. In 2021, there were 15,363 ED visits. Before the project, there was a vacancy in the quality manager role, and the hospital sepsis workgroup disbanded in May 2021. Therefore, this project began in October 2021 with the acquisition of a quality manager.

Methods

Interventions

Key members in the project’s planning included the director of Nursing, the ED nurse manager, the quality manager, and the medical director of the ED. Gaps in the process were identified with the frontline observations and input from the frontline staff and the critical nursing leaders via informal discussions. Based on the data and the feedback gathered, several changes were tested.

The team used the PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Act) methodology to test potential interventions to make the quickest impact on the hospital’s sepsis compliance.7

The Reboot of the Multidisciplinary Sepsis Workgroup

The first change was to reinstitute a sepsis work group in November 2021, inviting multidisciplinary hospital members to review sepsis metrics, discuss outliers, and plan improvement activities. We reinstated the workgroup to increase sepsis awareness and ensure a multidisciplinary approach when developing improvement interventions.

Initial attendance of the multidisciplinary workgroup consisted mainly of nurse managers and representatives from senior leadership and ancillary departments, including infection prevention, pre-hospital services, laboratory, and pharmacy. Physician presence in the workgroup started in February 2022. Small changes in the workgroup occurred over time. These changes included increased ancillary department involvement and meeting logistics, such as scheduling for physician availability.

Engagement in the workgroup and attendance were factors that significantly improved the productivity of the workgroup. Completion of action items along with outcome and process measures were monitored for effectiveness by the workgroup. Interventions targeted in the project were increased data transparency, awareness of sepsis triggers in triage, visual cues for sepsis triggers, and visual cues for best practice treatment interventions.

Awareness of Triage Nurse Screening

The quality manager completed an initial gap analysis that consisted of observation of current workflows and interviews with the ED frontline staff, physicians, and the nurse manager. A gap identified in interviews and observations was the need for more data to inform nursing leaders on the utilization of the sepsis triage question in the ED. A manual chart review process was developed to gather data using an existing EMR report to conduct retroactive chart reviews of patients diagnosed with sepsis. Data collected included whether the RN answered the sepsis triage question, the result of the screening, and the reason for the patient coming to the ED. Baseline compliance with the sepsis screening question was shared with the multidisciplinary sepsis work group starting in November 2021 and continued through December 2022. Interventions initially targeted data transparency and staff awareness. Discussions on the data for sepsis screening in triage were held at the workgroup meeting to analyze data and discuss trends. The ED nurse manager used the collected data to increase awareness by coaching staff on using the RN triage question. Nurse manager coaching of the staff showed an improvement in screening from October 2021 to January 2022.

The work group decided to continue to increase data transparency and staff awareness for the quality manager to provide data to frontline staff directly; a discussion of the importance of sepsis screening and RN screening compliance was included in the weekly staff huddle starting in January 2022. Further development of this intervention resulted from staff input regarding their compliance with screening being lumped together. Due to this, the staff needed help to discern whether they individually were being compliant with the triage screening. From this feedback, triage screening compliance scorecards with individual RN data were developed and shared with staff starting in May 2022. Scorecards were presented to staff monthly at unit staff meetings and sepsis huddles.

Increased awareness and data transparency assisted with improved nurse screening rates. The same concept was used to influence physician process metrics. Physicians were given performance scorecards, including sepsis best practice compliance, outlier reasons, and order set use in April 2022 (Appendix 1). These scorecards were shared with all physicians, the ED medical directors, and the hospital medical director. Increased visibility and leadership support with data support increased order set use.

Visual Cues of Sepsis Criteria

In the past medical record system, all sepsis criteria were visible within the triage screening process. With the new EMR system, the sepsis criteria were not visible, and the staff was asked to screen patients for a possible or known source of infection. At the same time, background analytics was used to determine if the patient met additional sepsis triggers. The fragmentation was hypothesized to contribute to missed RN triage sepsis screenings, as prior to this, the nurses would answer if the patient met any sepsis triggers, which could have led them to start thinking about sepsis.

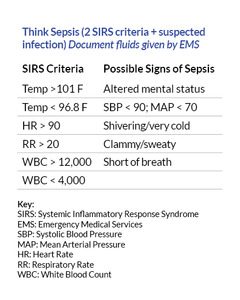

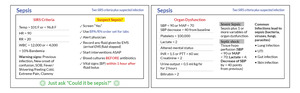

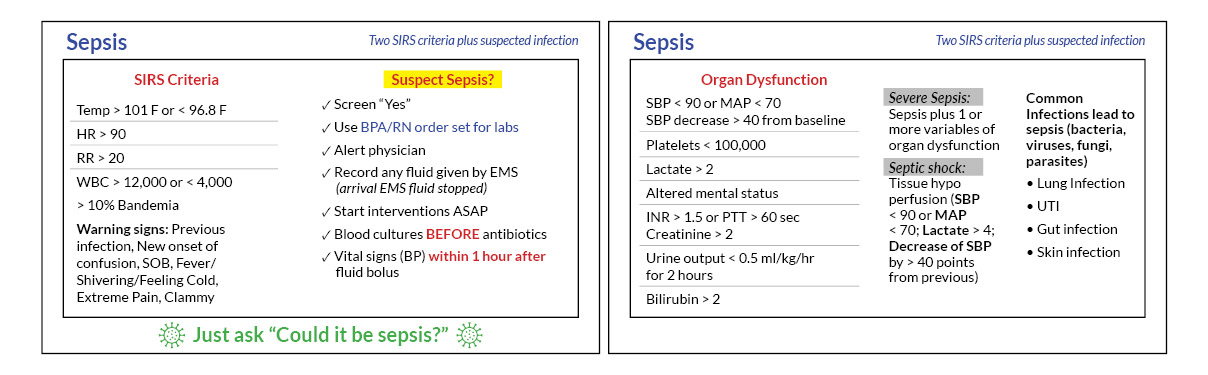

To address the fragmentation and increase the chance of considering sepsis, visual cues of the critical sepsis criteria were created to provide staff with sepsis information. The hypothesis was that the visual cue would aid as a human factors intervention by decreasing staff reliance on memory and reducing the cognitive burden. The first draft of the visual cue contained criteria and the appropriate sepsis interventions. The ED nursing director reviewed visual cues and gave feedback to condensing the information to only pertinent criteria to increase its visibility (see Figure 1). As a result, visual cues were placed at the top of the screen on the clinical computers used by the RNs in March 2022. At the same time, physician-facing visual cues were created to remind them of the elements of the sepsis best practices and critical factors contributing to decreased compliance (such as documentation points). Visual cues of sepsis criteria resulted in improved compliance with the screening question, and retrospective chart reviews showed an increase in accurate sepsis screening after implementing the visual cues.

In addition to attaching the visual cue card to the computer, it was determined that there was an opportunity to provide other references. A reference card attached to an identification badge, known as a “badge buddy,” was explored to complement the original visual cue card. The size of the badge buddies allowed the addition of other essential information, including sepsis process reminders (Figure 2). Badge buddies were rolled out to the emergency room nurses and physicians in August 2022. The use of badge buddies proved easy to implement, so much so that other departments (e.g., medical-surgical, intensive care unit [ICU]) began to adopt the concept to increase overall awareness of sepsis throughout the hospital. Frontline staff anecdotally felt the resource was valuable and minimized the need for those on the front line to remember all the pertinent information.

Network Change to Triage Question

In response to the increasing sepsis efforts, AHN changed the EMR to ensure the use of the RN triage question related to sepsis. When the triage question was not answered, it turned red to indicate the need for sepsis screening. Before this change, no indicator would alert a nurse that the sepsis triage question was unanswered. The sepsis screening question was in a line of other frequently used screening tools for triage and was found to be skipped past often. The hypothesis was that the visual cue would aid as a human factors intervention by decreasing staff reliance on memory of completing the triage question regarding whether a patient had a known or possible source of infection. After this change in August 2022, there was a significant improvement in RN triage screening compliance sustained in subsequent months.

RN Sepsis Escape Room

Though triage sepsis screening was increasing, there was significant variation in recognizing sepsis from nurse to nurse, likely because the experience of the frontline nurses in the ED ranged from new graduates to seasoned nurses. As a result, we identified an opportunity to support staff with critical concepts related to sepsis identification and treatment best practices, which we decided to address by designing sepsis escape rooms.

Escape rooms are an activity that can facilitate learning and engagement by using clues and puzzles to enhance staff retention of critical concepts.8 The concept for the sepsis escape room was created with the Simulation, Teaching, and Academic Research (STAR) Center at AHN. The escape room was conducted during ED RN education days. ED nurses were scheduled to run through the escape room, starting with a scenario and unlocking a set of six toolboxes, answering questions related to sepsis criteria and the treatment best practices. During the education days, 14 ED nurses attended the activity. Though feedback was collected anecdotally from attendees, formalizing pre- and post-tests were identified as a potential future improvement to evaluate the overall effectiveness of the escape room. The RN Sepsis Escape Room was completed in August 2022.

To expand sepsis knowledge and with positive ED feedback, the sepsis escape room was modified for other nursing units in the hospital, including the medical-surgical unit and ICU. It was implemented in those units in October 2022. Nine ED nurses missed the initial escape room education and were required to attend the October 2022 sessions.

Measures

Patients who met CMS sepsis core measure criteria were abstracted by abstractors within AHN after hospital discharge. The abstractors provided measures in a monthly graphical format in Tableau, a data visualization software. Outcome measures for the project included compliance with sepsis treatment best practices and sepsis mortality for the hospital based on the CMS sepsis core measure.

Process measures used through the project included the completion rate of the triage nurse screening question and the physician order set use for sepsis. For this data, the EMR system generated a monthly report of patients who were given a clinical impression of sepsis after an emergency room visit by the ED physician. From the list, the quality manager completed retrospective chart reviews to identify whether the triage sepsis question was used or whether the physician used an order set.

Analysis

The effectiveness of each intervention was measured with process and outcome metrics. All metrics were displayed on run charts. In addition, sepsis treatment best practice compliance and mortality were tracked through the CMS sepsis core measure abstraction and shown in Tableau. Data was updated as abstraction progressed. Run charts were also used to display process measures and were updated monthly by the quality manager after completing chart reviews.

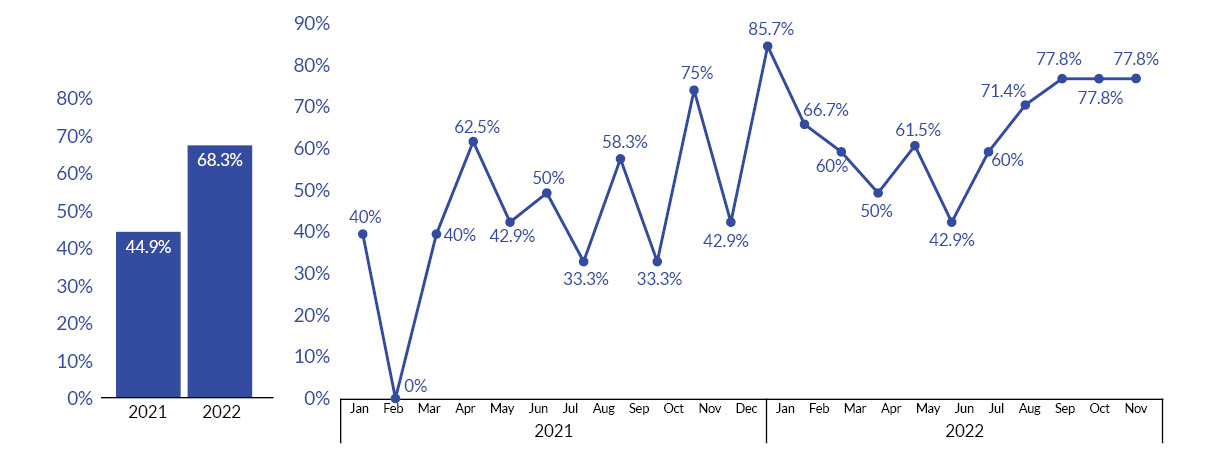

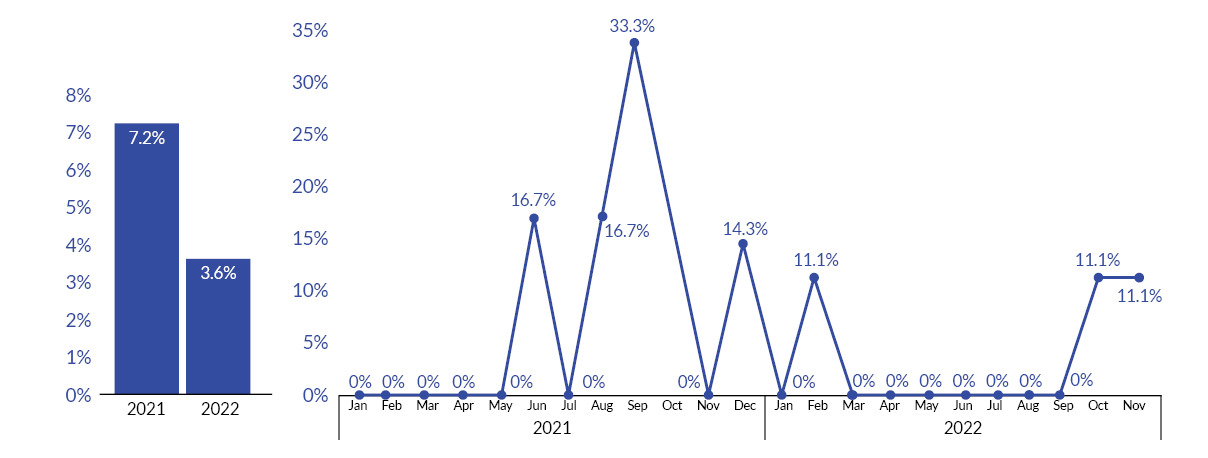

Results

In 2021, the hospital’s compliance with the sepsis best practice treatment was 44.9% (n=69). As of November 2022, the hospital compliance with sepsis best practice treatment was 68.3% (n=82). (See Figure 3.) In 2021, mortality was 7.2% (n=5), while as of November 2022, mortality was 3.6% (n=3). (See Figure 4.)

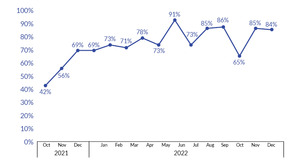

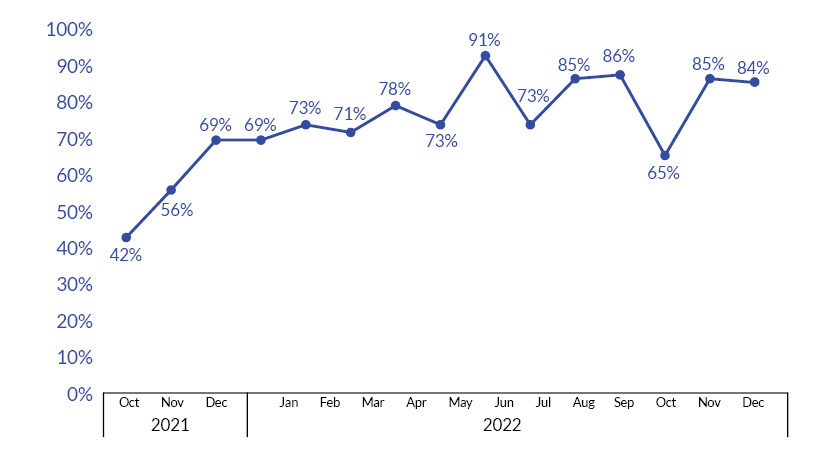

At the start of the project, there was 42% compliance with RN sepsis triage screening. The screening fluctuated during the project (56%–91%) but achieved a mean of 78.5% from February 2022 through December 2022. (See Figure 5.)

Physician use of the order set started at 8% at the beginning of the project. In January 2022, compliance increased from 8% in December 2021 to 38%; however, variation was noted throughout 2022 (18%-71%). (See Figure 6.)

Discussion

Summary

Implementing the interventions resulted in improvement toward the initial aim of 50% for sepsis best practice treatment compliance by increasing by 23 percentage points from the previous year. Sepsis compliance at the hospital as of November 2022 was above the national and state average at 68.3%. In addition, all process and outcome measures showed improvement for the current year.

Interpretation

It was noted that there were marked improvements from the prior year with some variability and opportunity for sustaining improvements in the project period. We discovered that reducing the cognitive burden of remembering all sepsis criteria and treatment allowed frontline staff to focus on utilizing screening and treatment tools to increase sepsis best practice compliance.

Lessons learned included guiding interventions from observations and direct feedback from frontline staff. Using data was imperative to show the need to make process changes to the frontline staff.

Challenges throughout the project included a surge of the coronavirus, which occupied the frontline staff in direct patient care and screening for signs and symptoms to apply isolation precautions properly.

Limitations

The project interventions were conducted in one community hospital, which may have limited the population. Another limitation of the project was the short length of time monitored. Reports were generated from the Epic EMR system; other systems may not have similar functionality. Limitations were also noted with the EMR as reports were not provided in real-time to identify patients who met sepsis criteria.

Conclusion

Technology advancements and healthcare changes are inevitable, especially in community hospitals. Observations of processes intending to drive meaningful improvement can identify key opportunities to implement human factors interventions which have been shown to assist frontline staff in decreasing the reliance on memory and increasing the quality of care. Staff engagement can be improved with data transparency and awareness, and help lead to the development of crucial resources for the identification and treatment of sepsis patients.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank the ER manager, Pamela Dolling, BSN, RN, for her assistance during the project.

Disclosure

The author declares that they have no relevant or material financial interests.