Introduction

At a community hospital in the Northeastern United States, a gap analysis revealed that a process change was needed regarding moderate sedation documentation so that adverse drug reactions (ADRs) were more readily captured. This documentation change would require education for the registered nurses in the departments that perform sedation. The challenge was that a third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was severely impacting the hospital concurrent to the process improvement project.

Moderate sedation is the practice of methodically reducing patient consciousness to allow a patient to tolerate painful or invasive procedures. Procedural sedation and conscious sedation are equivalent terms to moderate sedation. Moderate sedation carries regulatory reporting requirements and evaluation of any adverse drug reactions.1

The COVID-19 pandemic eroded healthcare environments with its impact on census, mortality, and staffing. The length of the pandemic from surges of virus variants stripped away previously used interventions, such as off-unit education for many nurses. The need to keep all available nurses at the bedside dictated that interventions were done in the clinical setting.

Problem Description

Baseline data revealed that ADRs were not consistently identified for evaluation. Moderate sedation audits did not capture any ADRs in a two-year window, which was unlikely and did not match with data from prospective ADR surveillance done via the pharmacy. The Moderate Sedation Committee needed to develop a process to better document when ADRs occurred so that they could be evaluated. This documentation change would create the need for process improvement, and in the challenging climate of the pandemic, the hospital needed a flexible and novel way to implement that process change.

Available Knowledge

Moderate sedation requires prudent administration, management, and monitoring. The moderate sedation program at the hospital is based on guidelines from the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). The guidelines prescribe best practices based on relevant literature and expert consensus. The guidelines include a quality improvement element in which ADRs are evaluated.2 In order to meet this requirement, accurate data on ADRs are essential.

Regarding education on moderate sedation, Werthman et al. queried hospitals across the country and found that the common practice was annual education combined with advanced cardiovascular life support.3 This matches the process at the community hospital, where the education is completed online. Because of the nature of the documentation change, updating the annual online education was determined to not be sufficient to ensure meaningful practice change.

Available literature on improving documentation is scant. In one study done specifically on interventions to improve documentation, Moldskred et al. found that effective interventions were to provide educational sessions as well as feedback from ongoing auditing on performance.4 This concept was used when planning the education intervention in the emergency department (ED). The education sessions started with a case study of a recent patient and audit feedback. In addition, feedback from ongoing audits was shared with registered nurse (RN) documenters across the hospital.

A key element to this process improvement project was the use of theory in building the interventions. Complex adaptive systems, the chosen theory, is part of complexity science and recognizes the importance of the relationships and the interconnectedness of all processes. Healthcare is a dynamic system with many elements and countless interactions. Change is not linear in dynamic systems; therefore, effective change management requires that new processes are able to be embedded into workflows without significant disruption. Complex adaptive systems do not have a single point of control and require distributive decision-making.5 Applied to this setting and process improvement, the success of new documentation is dependent on the nurses to recognize the importance of accurate documentation and the ability to easily embed it in their workflow. Distributive decision-making occurred when bedside clinicians created the new documentation. Support from leadership includes feedback from ongoing auditing.

Rationale and Aims

This project was designed using complex adaptive systems theory to change moderate sedation practice to reach the goal of identification of ADRs for analysis by the Moderate Sedation Committee. ADR evaluation is part of a robust moderate sedation program. The challenge was that while ADRs were managed appropriately when they occurred, the documentation did not highlight that an ADR occurred, and the audits missed them. Without the ability to consistently identify ADRs, the program could not evaluate performance and safety. A change to the documentation and the audit process were designed to remedy this concern. Complex adaptive systems theory guided the steps of intervention so that the new process would be successful.

The aims of this project were to deploy the new documentation so that ADRs were readily identified for analysis by the Moderate Sedation Committee and to minimize interruption to the clinical environment. The strategy for deployment was education and ongoing auditing with feedback.

Methods

The setting for this process improvement is a 200-plus-bed hospital in Northeastern Pennsylvania, part of a five-location nonprofit health system and academic center. Moderate sedation is performed in select areas only: interventional radiology, the ED, the bronchoscopy suite, and (rarely) critical care. Medications used for moderate sedation in the hospital are primarily benzodiazepines and opioids, with the ED also using ketamine, etomidate, and propofol. Each area has their unique characteristics that affect change. Interventional radiology has a small staff of seasoned RNs, as well as the greatest volume of moderate sedation. The ED has a large staff, a mix of new and seasoned nurses, and a low volume of moderate sedation, which means that the RNs do not have the opportunity to become proficient with the documentation. The bronchoscopy team has low volumes and a small staff to train, and the critical care areas perform moderate sedation so rarely that proficiency with documentation is not a realistic goal. The timeframe for the project began in June 2021, and documentation changes were enacted in February 2022. Data collection ran for eight months after the intervention.

Intervention

The gap analysis at the community hospital revealed that ADRs were not consistently reported with the original documentation process. This spurred the need to change documentation so that ADRs were readily identified. Because of the importance of the project, it was determined that the project needed to proceed and not wait for a calmer time. The challenge was identifying how to create this change in the current environment. Prior educational interventions were performed by holding in-person classes or lunch-and-learn opportunities, neither of which were feasible given the pandemic and the staffing challenges.

To meet the goal of identifying ADRs more readily in the documentation of moderate sedation, the Moderate Sedation Committee performed multiple Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles. The first cycle was the initial interdisciplinary committee reformation. The committee had been on hiatus during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and several of the stakeholders had changed positions. The committee was comprised of nursing, providers, quality and safety, pharmacy, and hospital leadership. The committee performed a gap analysis using ASA guidelines to identify needs. The data gathered revealed that only two ADRs were identified since committee reformation, and zero ADRs in the preceding two years, which was an unlikely scenario. The committee decided to update how moderate sedation was documented in order to address this gap.

The process to change the documentation started with soliciting feedback from end users and looking to see what was routinely missed from the documentation. As the documentation was lengthy and duplicative, it was shortened by removing unnecessary information and consolidating several sections. A section specific to ADRs was added to capture any patient reactions. The options included apnea, oversedation, use of reversal agent, significant change in vital signs, vomiting, and a free-text “other” field. The end users validated that the new documentation met their needs and was an improvement over the prior method. The new documentation was then finalized, and plans were made to launch it.

Education was the primary route to launch the new documentation. The education was personalized to each department. The leaders from each area served on the Moderate Sedation Committee and identified the best methods for their areas. For the areas with small staffs, the education was done on a one-to-one basis by the RN educator. These departments have seasoned staff and minimal turnover. In addition, leaders from each area, such as RN educators or expert evaluators, served on the Moderate Sedation Committee and were charged with personalizing education for their department. Education focused on the addition of the ADR documentation and the changes to shorten documentation.

The leaders also evaluated methods of how new and seasoned staff were educated and how competence was measured and maintained at this time. They identified several areas for improving current training methods of new and seasoned staff. One area that was evaluated was the practice of using online training modules. While the online modules adequately provided information regarding the administration of moderate sedation, the group felt that individual observations were needed. Interventional radiology (IR) was able to implement this during this study. In addition to the online learning modules, the educator in IR observed the staff member administering moderate sedation to five patients as part of their requirement for orientation into IR nursing.

The committee recognized that the ED needed a different plan, given that the environment was dramatically different than interventional areas. The one-on-one training that fit the interventional areas was not feasible in the ED. In addition, the staffing mix included seasoned nurses, new graduates, transfers from other departments, and agency nurses, representing a wide skill mix. While planning for the education in the ED, the COVID-19 pandemic’s third wave was cresting, fueled by the omicron variant. This impacted the ED with abnormally high volume along with managing staff sickness. The ED nurses could not come off the floor for training sessions because of this volume. Ideally, this education would have included simulation, but that was not realistic given the healthcare climate.

To overcome these challenges, the leadership of the ED partnered with the Performance Improvement Department to create focused, brief trainings able to be delivered during the shift huddles. The education method selected was just-in-time (JIT) training. JIT traditionally is used to train groups of people on a process just before it is performed and has been used previously in the COVID-19 pandemic. A hospital disaster team in Italy used JIT to train 200 staff members on disaster medicine and personal protective equipment in an environment of anxiety and urgency, and found JIT training effective.6 While the third wave of the pandemic did not rival the challenges faced in Italy during the first wave, JIT training stood out as the reasonable solution for the moderate sedation education. JIT use has been reported in the hospital setting to educate nurses on clinical deterioration.7 The relevance of this study is that the nurses appreciated education brought to the bedside and the education increased nurse confidence in identifying deterioration.7 Looking at complex adaptive systems theory, to achieve meaningful change, one must capitalize on relationships, such as the one between the Performance Improvement Department and ED leadership, and create change that is appreciated. Huddle was selected as the location of training to bring the change to the nurses rather than pulling them out of their environment.

Prior to the education, the leadership from the ED provided a warm introduction to the Performance Improvement staff doing the education for the ED staff. The education started with a case study based on a recent ED patient who had an ADR, and then education on adverse reactions and the new documentation was done. Several aspects of the new documentation were highlighted based on chart audits of what was commonly missed being charted prior to the intervention. This education was repeated multiple times over a two-week period to capture the majority of the RN staff.

The RNs were asked to complete a survey before and after the JIT training that measured their confidence in administering moderate sedation, identifying ADRs, and documenting the ADRs. There was an open field for any comments or questions that were not addressed in the education. These surveys were distributed on paper just prior to the education. Fruit and candy were also provided to the ED staff at all sessions.

Once the education was complete, the new documentation went live. The last PDSA cycle was establishing meaningful audits. New monthly audits were performed with a different format from previous years. The updated audit captured more data about the patient, the providers, the procedure, and the clinical aspects. The audit included any aberrant vital signs in addition to ADRs, and interventions to treat instability. Completeness of documentation was included in the audit based on the gaps found on prior audits. The auditors had the responsibility to provide feedback to the documenting RNs for anything missed. The feedback was informal and nonpunitive, given face-to-face or via email. When charts were found to be complete, those staff were celebrated.

With the data from the audits, the Moderate Sedation Committee was able to collate the information and create reports detailing how moderate sedation was provided at the hospital, including ADRs. This data analysis ensured that the moderate sedation practices were safe and that patients had the expected outcomes from the procedures, which the committee was able to confirm.

In the ED, documentation errors were more persistent. This may be due to the low volume and large staff. Certain elements were routinely missed in the charting. Because the audits identified these gaps, in addition to personal feedback, the elements routinely missed were added to ongoing education in the department.

Study of Intervention

Improvement in documentation of moderate sedation and ADRs was measured in two ways: a confidence survey and chart audits. In the ED, a convenience sample of RNs completed a pre- and post-JIT survey. Chart audits were completed to identify ADRs and completeness of documentation. Documentation was considered complete when it contained complete sets of vital signs at expected intervals, including cardiac, respiratory, and neurologic assessment.

Measures

The pre- and post-survey for RNs included four Likert scale questions about confidence administering moderate sedation as well as recognizing and documenting adverse events and an open field for questions or comments. A chart audit template was created using a spreadsheet which collected clinical information on the procedure, documentation completeness, and any adverse events identified. The pre-intervention chart audits were retrospectively done via randomly selected moderate sedation cases for the interventional areas. Because the ED had a lower volume of moderate sedation cases, all identified moderate sedation was audited. The audits were looking for ADRs and classified ADRs as either identified or latent. A latent ADR is one that was treated at the time but not flagged for evaluation by the Moderate Sedation Committee. An identified ADR is one that was found in the previous audits and was evaluated by the committee. The goal was to improve the documentation to stop latent ADRs and ensure that all ADRs were identified promptly for evaluation.

Analysis

The RN survey data was collected by providing a paper survey to participants with the pre-survey on one side and the post-survey on the other, allowing for matched samples. The chart reviews were done using the electronic medical record and collected in a spreadsheet.

Statistical analysis was performed using statistical software, SAS 9.4. Measures of central tendency were reported as means ± standard deviations (SD) for RN survey 5-point Likert scale questions (1 “Not confident” to 5 “Very confident”) and were compared between pre- and post-intervention studies by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. To avoid the possibility of incorrectly rejecting a true null hypothesis, a critical significant level of 0.01 (two-sided) was used. The chart audits data were categorical (either positive or negative for adverse events or documentation flaws). An element included in this analysis was whether an adverse event was identified or latent. An ADR was considered latent if it was not brought forward as a case to review. Frequency and percent were calculated and the association between intervention and ADR identification and documentation gap were measured using chi-square or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate, and a two-sided significant level of ≤ 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

This process improvement project was approved by the institutional internal review board and did not require informed consent. Ethical consideration was given to the timing and delivery method given the mental and physical demands of the RNs in the current healthcare climate. This consideration helped form the methods used to disseminate the new documentation.

Results

Data collection was done using a nurses’ survey and chart reviews. The survey measured nurse knowledge and confidence on adverse events and documentation (Table 1). Four questions were answered by the same nurse in pre- and post-survey, using a Likert scale of 1 to 5. A total of 34 nurses completed these four survey questions. In question 1 (Q1: Identify Adverse Reactions), post-survey achieved significantly higher mean score than in the pre-survey (Table 1, 4.59 and 4.29 respectively, p<0.01). Similar significant higher scores were shown in Q4 (p<0.01) and Q5 (p<0.01). Although post-survey had a higher score in Q3 than in pre-survey, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.13). In general, the mean scores on the post-survey were higher than the mean scores on the pre-survey.

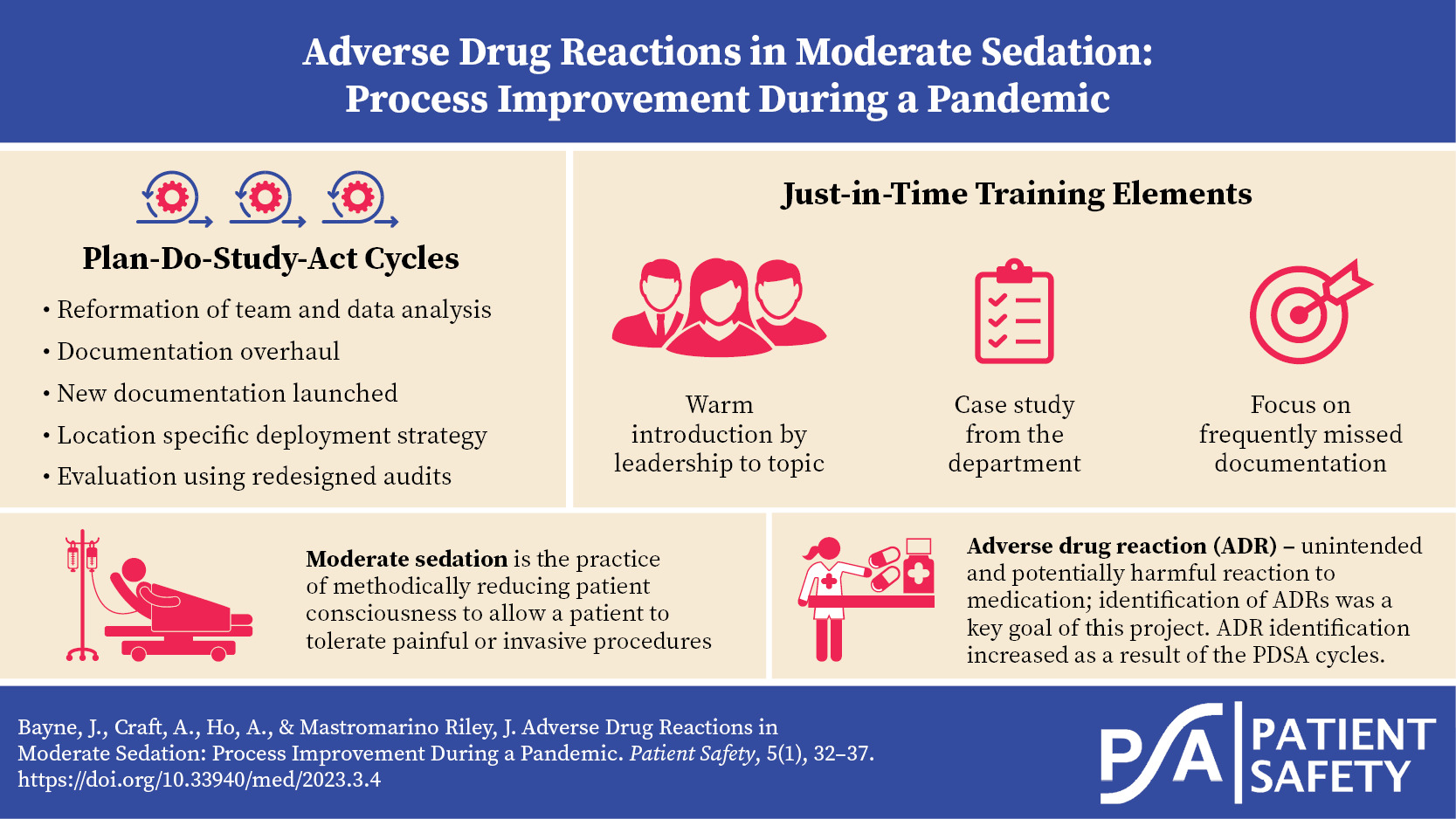

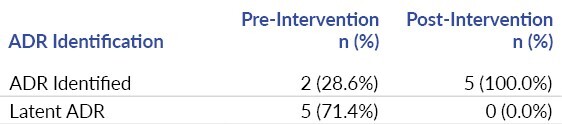

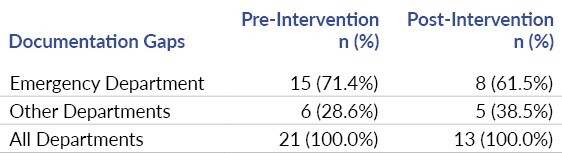

The chart audit data collected categorical data, the presence of ADRs, whether the ADR was identified or latent, and the completeness of documentation. Chart audits showed that there were seven adverse drug reactions in the 12-month pre-intervention audit period (Table 2). Two were identified at the time and five were latent. Following the intervention, five ADRs were identified over eight months, none being latent. The decrease in latent adverse drug reactions was statistically significant (p=0.03). Documentation completeness did not significantly improve, though it has increased since the intervention (Table 3); specifically, in the ED where the JIT training was done, documentation errors decreased from 71% prevalence to 62% prevalence.

Summary

Updating the moderate sedation documentation during a pandemic required the team leading the change to thoughtfully match the dissemination interventions to the environment. The new documentation was disseminated in the ED starting with a brief education session delivered at routine huddles. This was a successful intervention, as the survey results demonstrated the RNs increased confidence in the documentation and the documentation itself was more complete. Rollout to other areas using a one-on-one method was also successful regarding ADR capture based on chart audits. After rollout, more cases of adverse events were identified than with the old documentation, which allows for a stronger review of moderate sedation practices. The audits ensured that any adverse events were identified and were used to evaluate the completeness of the record. The documentation of sedation improved significantly because of the feedback.

Discussion

This project ensured that the new documentation for moderate sedation was effectively enculturated into workflows. The new documentation was designed with members of the clinical staff, increasing the likelihood of success. The method to disseminate the change was created based on the literature and an assessment of the ability of RNs to learn in a chaotic environment brought by a pandemic and its impact on census and staffing. In the ED, particularly impacted by the pandemic as well as low volume of procedures compared with a large staff, the results of the survey demonstrated that the education method was successful. The RNs felt more confident that they were able to identify and document ADRs. The chart audits demonstrate that the changed documentation forms and the focus on adverse events increased proper identification. This is crucial because adverse drug reactions must be analyzed on several levels, including by the Moderate Sedation Committee.

Interpretation

The timeline was longer than a usual documentation change. The audit/feedback cycle was key for staff improving on documentation. Moving forward, the audits can identify process issues and problems found can spur the next round of education. The process of making this documentation change required a change in focus from creating education and expecting adherence to working more closely with the RNs. The key difference was that the process was designed to meet the nurses where they were. It has changed the approach of how new changes are rolled out in the hospital.

Limitations

The limitation of performing a process improvement cycle in this method is that it requires flexibility and ongoing efforts. Unlike a class or online training that is completed and done, this approach needs more time from the leadership. To mitigate this, the work is divided among departments with support from Performance Improvement. The ongoing time to work on moderate sedation is a proactive patient safety measure that is valued in the organization.

Conclusion

This process improvement was designed for the specific environment at the time of intervention, with high census and tight staffing. Molding a set of interventions to the environment instead of performing process improvement tasks without consideration of other pressures was the key design element. This is generalizable to all process improvements with a scope far beyond moderate sedation. Process improvement in challenging conditions is possible. For success, the process improvement must be of high value, the interventions must fit with the current environment, and the leaders must be willing to change perspective on implementation. Using this method, the hospital was able to evaluate the moderate sedation program and ensure optimal patient safety.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cheryl Crozier, BSN, RN, and Lois Rajcan, PhD, RN, for their help.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.