Introduction

Healthcare providers involved in serious clinical errors; who have witnessed significant patient or employee trauma; or who have experienced critical incidents, such as the intense COVID-19 pandemic,1 are second victims, wounded healers,2 or walking wounded.3 The term “second victim” has been adopted across healthcare settings.4 Second victims are healthcare providers involved in unanticipated adverse patient events, medical errors, and patient-related injuries, and traumatized by these events. They feel responsible for unexpected patient outcomes, think they have failed their patients, and second-guess their clinical skills and knowledge base.3

Examples of situations or incidents that result in the second victim experience include sudden death or deterioration of patients;5 assaultive, violent patients or family members;5,6 complications of treatments;3 traumatic injuries of patients;7 multicausality disaster or terrorism events;7 unexpected pediatric deaths;5 and medication errors. Healthcare providers involved in extraordinary situations bear the wounds of patients, family members, and healthcare team members.8 They live with many consequences of traumatic experiences and may not be able to address or resolve the personal or professional effects of them.

The personal, substantial effects of provider involvement in traumatic situations for second victims are numerous and disrupt many relationships, such as with patients.9 Emotional responses consist of anxiety, shock, panic, inability to perform direct patient care, post-traumatic stress syndrome, self-blaming, worry, vulnerability, fear of punishment, moral distress, insomnia, helplessness, sadness, grief, depression, shame, intrusive reflections, flashbacks, emotional outbursts, suicidal thoughts, social isolation, denial of an incident, doubt of clinical knowledge and skills, and threatened professional identity. Physical reactions are fatigue, rapid heart rate, increased blood pressure and respirations, and muscle tension. Professional concerns for second victims consist of a potentially career-ending outcome, such as damage to reputation; being blamed, singled out, or exposed in a public tragedy; lost confidentiality; inability to escape the trajectory of events; stigmatization; documentation in the employee record; licensing board disciplinary action; litigation stress; criminal charges; imprisonment; and termination from position.5,8,10–17

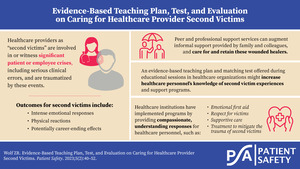

Family members and fellow employees often provide informal support to second victims; however, after recognizing the threats linked to outcomes for healthcare providers and other staff resulting from traumatic situations, leaders have initiated strategies and programs to support and retain wounded personnel and have addressed the implications of publicized errors and other traumatic events. Concern about all victims, patients and family members, employees, and healthcare institutions have impelled healthcare administrators to manage risk, provide peer support services, refer to employee assistance programs and psychological counseling, and create and implement evidence-based second victim programs. Expert recommendations have guided programmatic plans consisting of compassionate and understanding responses to traumatic situations, supportive care, respect for victims, treatment recommendations, and transparency.16 Programs have incorporated principles of Critical Incident Stress Management programs,7,18 Scott Three-Tiered Interventional Model of Support,3,19 Medically Induced Trauma Support Services (MITSS),20 and the Resilience in Stressful Events Program (RISE).21 The support provided to second victims can advantage healthcare institutions and match the fourth Quadruple Aim by fostering the well-being of healthcare providers through safe and healthy workplaces.22

Content on the impact of traumatic, critical incidents for providers and on the characteristics of effective programs supporting them needs to be disseminated. Knowledge of the experiences of second victims and targeted programs could assist healthcare leaders in providing interventions that prevent outcomes such as second victims’ sustained suffering, absenteeism, and leaving their professions. Therefore, the purpose of this educational initiative was to create an evidence-based teaching plan and matching test of knowledge concentrating on traumatized healthcare employees’ experiences and second victim support programs. The evidence-based teaching plan and multiple-choice test were framed by related literature; the project’s future aim was to disseminate the plan and the multiple-choice test to the global community, including university faculty, professional development educators and leaders of healthcare institutions who might use the plan as a basis for teaching sessions. The project’s questions were: What were the literature- and expert-validated components of a teaching plan and pretest on second victim experiences and support programs? What were the results of a pretest, matching the contents of the evidence-based teaching plan, on volunteers’ knowledge of second victim experiences and support programs?

The following conceptual definitions were used. Critical incidents are complex, varied, and multicausal adverse and traumatic events occurring in the delivery of healthcare experienced by patients, family members, hospital employees, and leaders that witness and participate in these situations.12,23 Second victims are healthcare professionals traumatized by critical incidents in healthcare environments, which suffer secondary traumatic stress when caring for traumatized patients,23 resulting in personal and professional repercussions3,24 and needing immediate and sustained support.

The teaching plan on the second victim experience and support programs is an evidence-based blueprint and four-column structure. The logical pattern of the teaching plan is aimed at enhancing healthcare provider knowledge.25 The entire plan or its parts can be used to orient an educational intervention for healthcare students and employees. The cognitive domain content column is framed by evidence-based research and peer-reviewed articles addressing facts, principles, and theories on second victims’ experiences and targeted support programs. The multiple-choice test is an evidence-based exam on knowledge of second victim experiences and support programs. The test items match the content and objectives of the teaching plan. The time allotted to different sections of the plan during teaching sessions is deferred to clinical educators. The evaluation methods are the multiple-choice test questions.

This study is framed by the theory of nurses’ psychological trauma.26 The theory examines traumatic situations that result in physical and emotional stress reactions for nurses when providing routine nursing care. Foli categorized psychological traumas as avoidable and unavoidable. The theorist described seven nurse-specific and nurse-patient-specific, acute or chronic, psychological traumas experienced during the act of caring. Although the theorist described one of the seven traumas, second victim trauma, the other six could cause nurses’ psychological injuries. Foli also noted the secondary traumatic stress responses associated with the nurse-patient relationship when nurses review their experiences. The author acknowledged positive (resilience, post-traumatic growth, compassion toward others) and negative (depression, anxiety, overinvolvement, substance use, compassion fatigue) outcomes of psychological trauma.26

Foli26 focused nurses’ psychological trauma theory on concern for nurses’ well-being. Foli charged organizational leaders to create an environment in which trauma-informed care supports nurses. As leaders resolve organizational problems, nurse-specific traumas might decrease nurse-specific trauma. Educational sessions based on a teaching plan could also reduce nurse trauma. Foli urged nurse leaders to provide critical support, since nurses are recipients of care and providers of care. Programs such as the Scott Three-Tiered Interventional Model of Support3,19 might reduce the effect of critical, traumatic incidents and experiences on nurses. Knowledge of second victim experiences might stimulate healthcare institutions to launch support programs.

Methods

Design

The project used a mixed-method design to develop a teaching plan as a basis for an educational intervention.27 Qualitative analysis of literature generated content areas of the teaching plan. Quantitative analysis evaluated the ranks reported by experts on the teaching plan and pretest drafts, and on results of the piloted pretest.

Face and Expert Validity Processes for the Teaching Plan

The project used content analysis methods to derive content areas of the teaching plan from printed versions of empirical and peer-reviewed literature. The citations, obtained through database search strategies (i.e., Summon, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, HaPI, and PubMed), used these search terms: “second victim,” “wounded healer,” “critical incident,” “program,” “employee support,” and “support programs.” The literature spanned several decades of published material on second victim or wounded healer experiences and support programs. Literature was analyzed using Hsieh and Shannon’s28 content analysis approach; the matrix is available on request. The draft teaching plan was grounded in peer-reviewed literature.

The nine sections of the draft and final teaching plan on second victim experiences and support programs include purpose, statement of overall goal, objectives, content outline, methods of teaching, and resources.25 Time allotted and methods of evaluation were not included because clinical educators may allocate preferred times to the teaching plan and the evaluation methods were the test items. The teaching plan (Table 1) was revised based on expert review.

Table 1.Healthcare Second Victim Experiences and Support Programs.

Purpose: The aim of the teaching plan is to provide an evidence-based content outline and matching test on the second victim experience and second victim support programs so that staff nurses and other healthcare providers deepen their awareness of the threats of critical incidents and opportunities for healing.

Goal: To educate students and employees of the healthcare professions about the second victim experience and corresponding support programs.

Objectives

At the end of the teaching session, participants will be able to: |

Content Outline |

Methods of Instruction* |

| Component 1: Second Victim Definition and Examples of Critical Incident Categories |

| 1. Discuss definitions of second victim (SV) concept and examples of critical incident categories. |

Definition

- Healthcare providers involved in a patient adverse event or medical error, and as a result, experience emotional and sometimes physical distress

- A healthcare provider involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event, medical error and/or a patient-related injury who becomes victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event. Frequently second victims feel personally responsible for the unexpected patient outcomes and feel as though they have failed their patient, second-guessing their clinical skills and knowledge.

- Potentially tragic implications for patients, family members, healthcare providers, healthcare institutions

Examples of Critical Incident Categories

- Care-associated (e.g., pressure injuries, falls), device malfunction, provider error, systems problems, medication, preventable harm to patient, surgery or other procedures, diagnosis, infections, acute patient deterioration, accidents, injury to provider, storms, terrorism, hostage situation in healthcare facility, active shooter in community

|

Lecture/ Discussion MP4

PowerPoint

slides |

| Component 2: Individual Effects of Second Victim Experiences |

| 2. Describe personal and public effects of being an SV. |

Emotional, Psychological, and Public Effects of Second Victim Experience

- Multifaceted responses to personal, vulnerable, experience

- Stress response: anxiety, worry, emotional upset, shock, horror, emotional trauma, emotional outbursts, burnout, panic, suicidal

- Depression: sadness, grief, despondency, helplessness

- Post-traumatic stress

- Feeling stigmatized, blamed, shamed, singled out, exposed

- Self-blame

- Personal failure: doubt clinical skills and knowledge, feel inadequate, threat to identity, intention to leave position

- Persistent recollections: relive event; intrusive reflections, flashbacks, haunted for rest of life, attempt to bury critical incident

- Spiritual and moral distress

- Disruption of daily activities

- Fear of punishment and termination from position

- Public tragedy: altered interpersonal relationships, social isolation, blamed for incident

|

Lecture/ Discussion MP4

PowerPoint

slides |

| 3. Describe common physical signs and symptoms linked to the SV experience. |

Physical Signs and Symptoms

- Physiological: increased heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, muscle tension

- Symptoms: headache, stomach pain, insomnia, fatigue

- Unexpected health events

|

|

| 4. Compare types of professional distress connected to the SV experience. |

Professional Distress: Institutional and Legal

- Institutional: career-ending situation, fear of retaliation, damage to reputation, loss of job, recorded in permanent employee record, threats, reprimands, lack of confidentiality, gossip

- Unit: avoid obtaining information about patient’s condition, avoid discussions of critical incidents with colleagues and supervisors

- Legal: dereliction of duty charge, fear of licensing board disciplinary action, lawsuits (litigation stress), criminal charges, imprisonment, inability to escape trajectory of events, acquittal

|

|

| Component 3: Second Victims’ Strategies to Mitigate Effect of Critical Incidents |

| 5. Identify professional, beneficial strategies initiated by SVs to reduce the negative effects of vulnerability after critical healthcare incidents. |

Professional, Ethically Based Strategies

- Report critical incident on discovery

- Acknowledge personal responsibility for incident

- Discuss safety threat with patient and family members

- Apologize to patient and family members

- Implement lessons learned in own clinical practices

- Demonstrate performance improvement activities

- Practice institutional patient safety initiatives

- Participate in safety conferences

- Make amends by sharing experience as lessons learned with healthcare providers

- Provide teaching sessions and speeches

|

Lecture/ Discussion MP4

PowerPoint

slides |

| 6. Evaluate self-care, healing strategies to decrease the distress of the SV experience. |

Healing-Promoting Interventions

- Obtaining psychological counseling

- Ongoing commitment to learning from incident and making constructive change

- Engaging in spiritual or religious practices

- Seeking supportive people with whom to share critical incident

- Practicing expressive writing

- Returning to work after receiving support

|

|

| Component 4: Professional and Unprofessional Responses to Second Victim Experiences |

7. Compare unprofessional to professional,

kindness-oriented responses of healthcare providers to SVs involved in critical incidents. |

Unprofessional Responses

- Isolate provider involved in error, neglect colleagues’ need for help, make light of colleagues’ responsibility for error, humiliate provider, condemn provider, punish provider, supervisor denouncement that provider that made error not allowed to give medications, transfer of involved provider to another clinical activity, assumption that second victims can manage situation themselves

Professional Responses

- Peer supporters: immediate support, share error stories, reassure SV of competency, establish trusting relationship, ask about emotional impact of incident and coping, avoid condemnation, practice attentive listening

- Peer support: evaluate if peer supporters have secondary traumatic stress, burnout. Measured by Professional Quality of Life: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue, Version 5 (ProQOL 5)

|

Lecture/ Discussion MP4

PowerPoint

slides |

| Component 5: Second Victim Needs and Recovery Stages |

| 8. Describe needs of SVs and stages of the SV recovery process. |

Second Victim Needs

- Sustained nonpunitive institutional culture

- Robust incident reporting system and response process

- Access to supportive colleagues especially in early stages to provide immediate, targeted support

- Systematic availability and support by easily accessible, multidisciplinary healthcare professionals in institution

- Acceptance by colleagues, and supervisors that emotions and reactions change over time, including socially undesirable feelings

- Continue supervisory relationship for new and seasoned clinicians

- Local unit and system improvements in response to critical incidents

- Supportive and constructive unit climate

- Institutional programs to develop diverse coping skills

- Yearly presentations on responses to tragic event programs implemented by institution

Six Recovery Stages of Hall & Scott

- Stage 1: Chaos and accident response (turmoil and need for support, self-recrimination)

- Stage 2: Intrusive reflections (haunted reenactments of situation, “what if?)

- Stage 3: Restoring personal integrity (seek support from trusted colleague, friend, or family, stabilize patient)

- Stage 4: Enduring the inquisition (concern about institutional repercussions, job security, licensure, litigation stress)

- Stage 5: Obtaining emotional first aid (seek emotional support from family, colleagues at work)

- Stage 6: Moving on-dropping out, surviving, or thriving (difficult to put event behind and move on)

|

Lecture/ Discussion MP4

PowerPoint

slides |

| Component 6: Peer Support Relationships Framed by Nursing As Caring Theory Concepts |

| 9. Describe strategies framed by caring theory to provide structure for colleagues supporting SVs in relationship. |

Team Members Involved in Critical Incidents Need Support to Navigate Experience

- Second victims: need kindness, reassurance, concern, understanding, counselling, time to reflect and learn

- Employees and interprofessional healthcare team need support and time to reflect and learn

Caring Actions Based on Nursing As Caring Theory Concepts and Scott & Hall Recovery Stages

Phase 1:

- Peers offer immediate support, or emotional first aid, to second victims engaged in caring nursing situation with them

- Peer supporters recognize that they and second victims are caring persons

- Peers and supervisors start to interact with second victims, are intent on and commit to learning about their experiences with critical incidents

- Peers commit to support and nurture second victims during their relationship as effects of incidents evolve

- Peers and second victims develop short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term relationships; supervisors may also support second victims at this time

- Peers value vulnerability of second victims and respect different expressions connected to incidents, such as hope, fear, grief, stress, self-blame, courage, humility

- Peers are attentive and listen to second victims

- After assessing safety of situation, peers escort second victims to another location if possible

Phase 2:

- Peers and supervisors continue to support and relate to second victims as they feel their personal integrity restored

- Second victims’ experiences are affirmed as peers and supervisors share their personal responses to critical incidents and effects on institution

- Peers and supervisors reflect on conversations with second victims

Phase 3:

- Second victims may continue to suffer from critical incidents calling for peers and supervisors to continue to be available and supportive, and to listen to their experiences

- Peers and supervisors care for second victims and note their surviving, thriving, moving on, or dropping out

|

Lecture/ Discussion MP4

PowerPoint

slides |

| Component 7: Effect of Critical Incidents on Healthcare Organizations |

10. Evaluate the institutional effects of critical incidents on reputation

of healthcare

organizations. |

Corporate Effects of Critical Healthcare Incidents

- Organization as third victim

- Goal: to foster a culture in which all employees were resilient and mutually supportive before, during, and after stressful events

- Second victim phenomenon as serious consequence for institution, public tragedy and influence on reputation, incident as corporate emergency, risk to reputation, product risks such as medication shortages

- Culture change of norms to safety culture, personnel knowledge of investigational process after events, need to understand long-term support may be needed, negative to positive attitude change, eliminate stigma, available psychological support through mental health services

|

Lecture/ Discussion MP4

PowerPoint

slides |

| Component 8: Organizational Process Improvement Strategies |

11. Describe

organizational process improvement strategies in support of SVs. |

Post-Critical Incident Strategies

- Open, nonpunitive approach

- Vigilant about patient safety

- Report but do not overreport constructive changes

- Support from unit managers, peers, supervisor, physicians, etc.

- Share “blame and shame” stories to teach staff about prevention of like incidents

- Share details of event with patients using informal and formal support, safety officer responsibility

- Debrief when emotional intensity subsides after critical incident

- Establish venue for discussing emotions after critical incidents

- Offer training and retraining sessions on civility, incident disclosure, and mentor and peer support

- Conduct root cause analysis in response to incidents

- Structure availability of supportive employees: risk managers, chaplains, social workers, mental health clinicians, child life therapists, palliative care practitioners

|

Lecture/ Discussion MP4

PowerPoint

slides |

12. Share examples of types of safety strategies implemented by

healthcare institutions to increase patient and provider safety. |

Examples of Technological Strategies

- Electronic adverse event reporting system, barcode technology, electronic health record, infusion pumps, error-reduction simulations, medication dispensing systems, intranet safety reporting systems, etc.

Examples of Safety Strategies Promoting Safety

- Develop and periodically assess culture of safety

- Emphasize systems’ roles in critical incidents

- Avoid blaming personnel for safety threats and critical incidents

- Maintain anonymous reporting system on intranet

- Manage root cause analysis processes

- Report safety risks and critical incidents to quality improvement, mortality and morbidity, and safety committees

- Apologize to patients and family members: patient safety officer or another administrator

- Facilitate smooth return of involved SVs to patient care

|

|

| Component 9: Program Creation and Implementation |

13. Describe institutional

principles and goals that orient SV programs. |

Program Goals and Principles in Support of Second Victims

-

Goal Examples

- To provide awareness of supportive strategies available to prevent clinicians and other healthcare employees from extreme stress after critical incidents.

- To identify the contributions of ongoing process improvement activities that periodically evaluate and modify programs targeted at supporting second victims.

-

Foundational Principles in Second Victim Program Development

- Program creation and implementation by committed, core interprofessional team

- Development of policies and procedures

- Proactive, consistent, timely support strategies

- Immediate post event first aid for involved employees

- Identification of professional referrals for psychological and other types of support services

- Systematic approach to education sessions, onboarding, evaluating, and maintaining program

- Periodic evaluation of program performance

- Periodic staff training

-

Team Engagement and Commitment

- Establish core multidisciplinary committee: clinicians, quality improvement, hospital leaders, safety experts, risk management

- Focus on Quadruple Aim: workforce well-being and safety

|

Lecture/ Discussion MP4

PowerPoint

slides |

14. Compare types of programs implemented by healthcare organizations in support of SVs

. |

Program Types and Organizational Strategies to Implement Programs Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM)

Multicomponent crisis intervention system: small and large scale applications

-

Provision of psychological support in field

-

Immediate, rapid support

-

Expectancy: viewing extreme stress reaction as normal and not pathological reactions

-

Best practices: early intervention, complete care, complete care, peer support, specialized training

- Core competencies: assessment and triage, crisis intervention with individuals, small-group and large-ground crisis intervention, strategic planning

- Critical Incident Stress Debriefings (CISD): Crisis debriefing, emergency responder involvement

Scott Three-Tiered Interventional Model: Framework of Caring–Support for Second Victims

- Tier 1: “Local” (Unit/Department) Support: all employees trained to know how to identify a second victim and how to provide initial support to a second victim.

- Tier 2: Trained Peer Supporters, Patient Safety & Risk Management Resources: Trained peer supporters, individuals who have been educated on conducting one-on-one and group debriefings, give further assistance to a second victim by asking appropriate questions and providing a listening ear.

- Tier 3: Expedited Referral Network-Trained professionals outside of the pharmacy department (e.g., pastoral care, employee assistance program, social work, and behavioral health staff) are contacted when care needs to be escalated and professional support is required.

Essentials:

- Team training of “clinician lifeguards”

- Administrative framework

- Monitoring rapid response system interventions

Toolkit for Hospitals on Second Victims–Institutionwide support program for clinicians

- Modular: multiple actions that could occur concurrently, best practices, evidence-based;

Modules: internal culture of safety, organizational awareness, multidisciplinary advisory committee; leadership buy-in; risk management considerations; policies, procedures, and practice; operational staff training communication plan; learning and communication opportunities

- Personnel: Identify core steering team; identify executive sponsor; develop unit-based teams; develop team branding/marketing; educate and train peer supporters; track data to insure effectiveness teams; funding initiatives; design of support system important for impact

- Implementation: Tool Kit for Healthcare Organization on Clinician Support Toolkit Plans for Program Implementation

RISE Resilience in Stressful Events (Johns Hopkins Hospital)–Peer support program: Provide

resources to reduce harm to self or others; confidential

- Initial peer support and active listening throughout; debriefing as learning opportunity

- Recruit and train peer supporters; apply to peer program; train peers; RAPID (Reflective listening, Assessment, Prioritization, Intervention, Disposition) psychological first aid; ongoing training; 2-tiered call system (2 peers, 1 as backup); % budget allocation for program director.

- Three-Tiered approach rapid response; 1 = rapid responders, peers; 2 = 24 x 7 rapid response from institutional experts; 3 = availability of professional support and counseling

|

Lecture/ Discussion MP4

PowerPoint

slides |

Note: Time in minutes is allocated to connect is specified by educator

*Citations included in References section of paper.

Multiple-Choice Pretest

The multiple-choice test matched the teaching plan. After revisions based on experts’ judgments, the test was piloted as a pretest with volunteer doctoral students (N=18 out of 28) before they examined content in a course module on healthy work environments including strategies, civility, and second victim experiences. The pretest was developed as an initial exam that could be adopted and modified by professional development educators.

Ethical Considerations

Institutional review board review approval was obtained under expedited review (IRB: 23-02-009). Data analyzed on the literature were textual. No names of content experts were identified. The test grade was not part of volunteer students’ course assignments. Eighteen students participated.

Instrumentation

Content Areas of the Teaching Plan: Analysis of Literature and Test Blueprint

The content areas of the teaching plan’s outline were generated through inductive, conventional content analysis of pertinent empirical and peer-reviewed literature on second victim experiences and support programs.28 The column headings of the coding matrix were major themes, minor themes, indicators from literature, and citations. Themes and indicators were selected to build the content outline statements for those components of the teaching plan.25 Face validity was established because the content areas of the teaching plan originated in second victim literature.27 Test items matched the teaching plan objectives and the content outline. Items were organized using a content specification matrix for subcomponents of the content outline and knowledge/comprehension, analysis, and application objectives.29

Experts’ Judgments on Content Areas of the Teaching Plan and Multiple-Choice Pretest

Seven experts were invited via email to judge the content areas of the draft teaching plan and test items using an expert validity form. The five anonymous, traditional, and experiential experts that participated were doctoral-prepared safety content and test construction experts.

The draft teaching plan consisted of nine content areas. Relevance of the content areas was elicited on a two-point scale for the content areas or components (0=vital part missing, 1=vital part present) and through comments. The teaching plan’s item content validity indexes (I-CVIs) and survey content validity average (S-CVI/Ave) were 1.0 for all components of the plan. Overall, experts’ comments were positive on the details of the plan. The indexes and comments supported content relevance.

The five experts critiqued the relevance of 22 test items. Test item relevance was elicited on a four-point scale (1=not relevant, 2=somewhat relevant, 3=quite relevant, 4= highly relevant) and through comments.26 The I-CVIs ranged from .83 to 1.0. The S-CVI/Ave for test items was 0.97. Changes were made to test items based on comments, such as grammar, modification of distractors, multiple-multiple items revised to multiple-choice format, and inclusive language use. The pretest of the multiple-choice exam was administered online via a learning management systems-formatted test during a course. Total scores were obtained.

Data Analysis

The four-column coding matrix (major themes, minor themes, indicators from literature, and citations) structured data analysis of literature that generated components of the teaching plan on the second victim experience and support programs. Inductive, conventional content analysis28 structured the analysis as the literature was read; themes were named and recorded in matrix columns and aligned with references. Minor themes were grouped into major themes. Quantitative data on experts’ judgments of the teaching plan’s content outline and test items were analyzed using Excel. Pretest item statistics and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient were analyzed using Canvas statistical operations (San Francisco, CA); recommendations vary on sample size for alpha coefficients.30 Descriptive statistics on the total score for the pretest were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics 28.

The credibility of the teaching plan and pretest was established by the expert content validity process completed on the content outline and test items. A seasoned qualitative researcher followed the audit trail of the content analysis, reviewed the revised teaching plan and test items, and approved the quality of methods and results.

Results

The content column of the plan was based on related literature, as supported by the coding matrix. Expert review supported the integrity of the nine components of the plan. The revised teaching plan is found in Table 1. It can provide structure for educators as they instruct healthcare providers on the knowledge of the second victim experience and available support options. The plan can offer guidance to educators and foster the standardization of teaching sessions in clinical settings.25 They most likely will conduct group sessions so that costs are contained. The teaching plan might be judged as internally consistent in that objectives match the other parts of each component.

The pilot test results were based on a Canvas-formatted exam administered to volunteer doctoral students (N=18, response rate= 64.3%). Descriptive statistical findings on the summed, correct items showed the following: M=8.09. MD=7.00, SD = 4.75. The mean on test-takers’ knowledge was very low, suggesting a need for educational sessions on the content. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .441.

The findings on pretest items are included in Table 2. The multiple-choice test item format was preferred to other formats because of rapidity of administration. Additionally, item test statistics assist in evaluating first-time administered tests, such as this example. Descriptive statistics on items (frequency/percentage of correct items, proportion correct indexes, or difficulty and discrimination indexes) can call attention to the need to consider revision. However, they do not confirm whether an item is good or bad.29 Negative and low discriminability values suggested the need to evaluate items for item revision. One item had extremely low discriminability because all test-takers answered the question correctly. Other items’ discriminability scores were also low. Students may not have known some details about the second victim experience. See Table 2 for more details on items needing revision. Correct items are bolded.

Table 2.Test Item Statistics on 22-Item Draft Second Victim Multiple-Choice Test (N=18).

| Item With Distractor |

N Items Correct (%) Difficulty or Proportion Correct Index |

Discrimination Index |

Revision Needed |

- What types of critical incidents result in healthcare provider trauma?

- Physical assaults on healthcare staff

- Unexpected patient deaths

- Deaths of children

- All of the above

|

18 (100) |

-0 |

Multiple-choice item with the new recommended distractor.

Extremely poor discriminability. Further revision may be needed. |

- Which best describes a personal and professional consequence of the second victim experience?

- Threatened professional identity

- Periodic emotional outbursts

- Frequent intrusive thoughts

- Self-blaming episodes

|

6 (33.3) |

0.30 |

|

- Which behavior further victimizes healthcare providers involved in very traumatic events?

- Gossiping about guilt of involved staff

- Avoiding discussions about the critical situations

- Making light of the incident during meetings

- Describing the situation in personnel records

|

5 (27.8) |

0.36 |

|

- Which result of a critical incident is a legal consequence linked to the second victim experience?

- Fear of State Board disciplinary action

- Inability to escape the situation

- Dereliction of duty charge

- Damage to professional reputation

|

4 (22.2) |

0.54 |

|

- What is a personal strategy used by second victims to alleviate the effects of their involvement in traumatic incidents?

- Discuss certain causes of the incident with many colleagues

- Implement practice changes based on lessons they learned

- Return to work as soon as possible on their assigned unit

- Query colleagues about their patient’s present-day status

|

7 (38.9) |

0.08 |

Punctuation revised. Low discriminability; further revision may be needed. |

- What is a personally motivated intervention of second victims to promote healing?

- Attending professional patient safety conferences

- Performing process improvement activities

- Discussing critical incidents with division leaders

- Participating in spiritual practices

|

18 (100) |

-0 |

Easiest item; based on knowledge; extremely poor discriminability. Revision needed. |

- What is the most important activity by peer supporters for second victims following critical incidents?

- Acceptance of report

- Targeted interventions

- Immediate support

- Facilitated coping

|

10 (55.6) |

-0.13 |

Poor discriminability; revision may be needed. |

- Which institutional characteristic frames second victim programs?

- Nonpunitive institutional culture

- Analysis of incident causes

- Correction of negative emotions

- Reduced access to supervisors

|

14 (77.8) |

0.29 |

|

- Which phrase best describes the intense experience of trained peer supporters of second victims?

- Long-term commitment

- Secondary traumatic stress

- Provider emotional first aid

- Skilled in emotion-focused coping

|

5 (27.8) |

-0.02 |

Poor discriminability; revision may be needed. |

- What is an example of type of long-term support needed by second victims?

- Safety nets for seasoned clinical peers

- Supervisory monitoring of unit-based practices

- Accessible multidisciplinary professionals

- Transfer to another clinical division

|

12 (66.7) |

0.11 |

|

- When second victims endure the post-incident “inquisition,” they predict that the institution’s leaders will conduct which of the following actions?

- Counseling by direct report supervisor

- Contributing to a failure modes and effects analysis

- Being fired from their position

- Receiving alternate unit assignments

|

7 (38.9) |

0.21 |

|

- A critical care nurse made a serious medication error. They attributed the error to medication packaging, nurse staffing, and a dilution miscalculation. The charge nurse immediately reassured them, shared stories of personal errors, and managed patient care. Which of the following describes the charge nurse’s response?

- Kindness

- Support

- Professionalism

- All of the above

|

14 (77.8) |

0.55 |

Revised gender language based on expert comment; revised to multiple-choice item. |

- A critical care nurse criticized their patient care as not being aggressive enough in treating a patient’s deterioration. After the patient died, they described very deep, very disturbing regret to the nurse manager; the manager listened carefully to the story about the experience. Which is the best caring intention demonstrated by the nurse manager?

- Committed to understanding their regret about their patient care

- Provided an opportunity for the nurse to reflect on the patient’s situation

- Critiqued the nurse’s missed opportunities to advocate for the patient

- Decided against reassigning the nurse to a different critical care unit

|

2 (11.1) |

-0.22 |

Grammar correction: plural; revised gender in distractor. Negative items have poor discriminability; further revision may be needed. |

- The goal of the hospital was to foster a culture in which all employees were mutually supported throughout the long-time pathway of critical, stressful events. Which of the following descriptions fits this goal?

- Leaders implemented plans to assure availability of mental health clinicians for second victims of traumatic events

- Division directors planned education for professional staff on how to actively participate in the root cause analysis process

- Safety officer discussed the incident which involved nursing staff before describing the fatal diagnostic error with the patient and family

- Supervisors continued to evaluate critical incidents by looking for provider-caused behaviors leading to future healthcare errors

|

12 (66.7) |

0.66 |

Most discriminating item. |

- Which of the following strategies implemented by healthcare leaders shows their continued support for employees following traumatic critical incidents?

- Support failure modes and effects analysis on preventing future, similar incidents

- Participate in an incident debriefing meeting with clinicians when emotions decrease

- Share details of the incident with clinicians in informal support networks

- Publicize the results of safety culture efforts periodically on institutional intranet

|

11 (61.1) |

0.45 |

|

- What is a strategic activity by clinical unit and divisional leaders that shows sensitivity and concern for second victims?

- Detect failure modes in high frequency error categories to target prevention strategies

- Report increased safety risks and statistics to employees through quarterly intranet messages

- Identify results of outcomes assessment on supportive programs provided for second victims

- Facilitate the return of clinicians involved in traumatic incidents to patient care positions

|

2 (11.1) |

0.37 |

|

- Which program served as a foundation for many second victim programs?

- Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM)

- Scott’s Three-Tiered Interventional Model of Support23

- Johns Hopkins Resilience in Stressful Events (RISE)

- Mitigating Impact in Second Victims (MISE)

|

4 (22.2) |

-0.02 |

Negative items have poor discriminability; revision may be needed. |

- What is a potential effect of publicized patient tragedies on involved healthcare organizations?

- Normative revision

- Challenge to mission

- Knowledge of community response

- Stigmatization in the community

|

13 (72.2) |

0.35 |

|

- In addition to guiding second victim programs in healthcare organizations, which of the following activities do core steering committee members perform to secure second victim programs?

- Report safety risks to quality improvement and other safety-oriented committees

- Ensure the anonymity of reporters to the institution’s intranet safety reporting system

- Notify new staff about components and members of an institution’s second victim program

- Advise leaders of healthcare agencies of the need for second victim policies and procedures

|

4 (22.2) |

0 |

Revision needed due to no discriminability value. |

- What is a clinician’s response to a serious patient-care error when employed in a healthcare institution with a nonpunitive culture?

- Freed from negative consequences of adverse events

- Reduced anxiety when reporting safety threats

- Increased security about preventing negative outcomes

- Limited accountability for personal recklessness

|

12 (66.7) |

0.36 |

|

- During a committee meeting, the chairperson of the second victim steering committee encouraged discussion on a highly publicized “shame and blame” story about a serious medication error of a registered nurse that resulted in a patient’s death. Which of the following shows the chairperson’s intent?

- Encourage reporting

- Avoid litigation

- Learn from error

- Prevent guilt

|

10 (55.6) |

0.2 |

Revised stem for flow. |

- The healthcare system’s second victim program was disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic; multiple stressors affected frontline staff. Which of the following strategies is the best action of the second victim core steering committee?

- Set baseline data using four months of data for year two of the pandemic

- Brainstormed to identify actions that might revitalize the three-tiered program

- Invited hospital leaders to sponsor an entire reboot of the second victim program

- Planned several programs that encouraged workplace engagement in changes

|

6 (33.3) |

0.31 |

|

Discussion

Crisis situations are occurrences in acute care hospitals and other clinical settings because of the nature of nurses’ caring work for patients and families. Therefore, second victims witness and participate in experiences that may be catastrophic. Those involved in serious incidents could benefit from initial and continued support after involvement in traumatic experiences in healthcare institutions, such as gun violence situations, partner violence, and child abuse. The emotional and professional effects of these events persist as an aftermath.13

The results of the pretest, although in initial development, suggest that knowledge about the second victim experience may not be well known or disseminated. The relevance of an evidence-based teaching plan and a test on the second victim phenomenon is that they can serve as resources for professional development educators when offering teaching sessions in healthcare institutions. The structure and details of the teaching plan can be easily modified by educators. The content of the teaching plan could also be included in a series of sessions.

Perceived institutional support for second victims has been described as contributing to the safety culture and decreased emotional exhaustion of clinicians.31 Organizations might retain skilled healthcare providers when emotional first aid is given and if resources continue to be available. Education of healthcare employees about the trauma of second victims might encourage healthcare professionals to develop peer support skills and offer them to colleagues.32

The teaching plan’s content areas need to be reviewed; the content analysis of the literature was conducted by one researcher. The plan and the test items, although supported overall by experts’ judgments of their relevance, call for future revision. The teaching plan should be modified periodically based on current literature. The test items need to be revised based on the item statistics and suggestions seen in Table 2.

Future research is needed on the effect on implementing educational sessions framed by the teaching plan on nursing staff’s knowledge of the second victim experience and support programs. The intervention is the teaching session and the outcome measure is the scores of the revised test. Researchers could conduct a pretest/post-test, quasi-experimental study comparing knowledge of the second victim experience. One group could be instructed using the teaching plan-based session and the comparison group would not receive the instruction.

Conclusion

Some healthcare agencies have adopted and sustained support programs for second victims that continued throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the need to recognize the pandemic’s effect on clinicians and organizations is a concern, as noted by Hall.33 Education and research on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are needed as clinicians reemerge from the pandemic and encounter future traumatic events.

Continuing education on the second victim experience is needed. The teaching plan should be updated periodically using evidence-based literature and test items need to be revised to fit changes. Although peer support may be preferred to other resources offered in second victim programs, the needs of affected staff need to be understood by nurses and their team members.1 The trauma felt by second victims can require professional counseling21 and long-term support services; peers that support them are not immune to the trauma. Educational sessions can increase awareness of support available;34 periodic education grounded in an evidence-based teaching plan could also enhance awareness so that when crises occur, clinicians might access institutional resources.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

About the Author

Zane Robinson Wolf (wolf@lasalle.edu) is professor of Nursing Programs and dean emerita at the School of Nursing and Health Sciences, La Salle University. She is a member of St. Christopher’s Quality and Patient Safety Committee and the Board of the Patient Safety Authority’s journal, Patient Safety. Her published books include Caring in Nursing Classics: An Essential Resource, Exploring Rituals in Nursing: Joining Art and Science, and Breaching Safe Nursing Practice: Case Studies of Failures, Omissions, Commissions, and Crimes. Dr. Wolf has been an editor of the International Journal for Human Caring since 1999. She is a former board member and past president of the International Association for Human Caring. She is a board member of the Anne Boykin Institute for the Advancement of Caring in Nursing.