Introduction

Problem Description

Hypertension is a global problem and a preventable risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease.1,2 Chronic, untreated hypertension is often asymptomatic. Therapists treat a wide range of patient ages and diagnoses, including individuals with cardiovascular disease, and are well positioned for early detection, screening, and timely referral. However, vital sign monitoring in outpatient therapy clinics, as reported in the literature, is infrequent and inadequate.3–5 Common reasons provided as to why blood pressure is not routinely, if ever, assessed are not enough time, lack of proper equipment, and “not important for my patient population.”6,7

Available Knowledge

The American Heart Association regularly updates classification of normal and abnormal blood pressure, defining a hypertensive crisis as equal or greater than 180/120 millimeters of mercury (Figure 1). Hypertension affects approximately 50% of the adult population in the United States, with 20% unaware of their condition.1 Untreated hypertension is associated with the development of coronary artery disease, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke, with heart failure the number one hospital-admitting diagnosis.8 Heart failure alone is projected to burden the United States with more than $50 billion in healthcare costs by 2030.9

Published literature finds a lack of blood pressure monitoring by outpatient physical therapists for patients with both known and unknown cardiovascular disease. A majority of outpatient therapists surveyed acknowledged the importance of monitoring blood pressure, but less than half reported actually assessing it.3–5 The American Physical Therapy Association’s Guide to Physical Therapist Practice recommends cardiovascular and pulmonary screening of every patient as a component of the Patient Management Model.10

Despite screening recommendations from multiple professional organizations,10,11 significant prevalence of undiagnosed and untreated hypertension, and therapist acknowledgement of the importance of monitoring, blood pressure is not routinely assessed. Thus, the question to ask ourselves as therapists is how to implement a sustainable plan to address this lack of monitoring.

Setting/Context

Good Shepherd Penn Partners in Philadelphia is the official therapy provider for Penn Medicine and employs approximately 200 outpatient occupational, physical, and speech therapists. The 25 outpatient clinics span urban and suburban locations across Pennsylvania and New Jersey, averaging 39,000 new evaluations per year. A wide range of patient ages and diagnoses are treated covering multiple specialty areas, including orthopedics, hand therapy, pelvic floor, sports medicine, lymphedema, and neurology. Although therapists are educated in school to assess vital signs, a majority of therapists do not routinely include vital sign monitoring as a regular part of their practice. Prior to this project, no guideline existed to support therapists.

This project implemented an evidence-based guideline, with support and collaboration of clinicians, managers, and organizational leadership, with the primary goal of improving patient safety by detecting asymptomatic, dangerously high blood pressure. This quality improvement project was implemented across all outpatient clinics in fall 2019 and originated when a therapist requested guidance on best practice for monitoring ambulatory patients with cardiovascular risk factors. In consultation with multiple partners, including therapists, managers, administrators, and physicians, it became clear action was required. This work began with launch of the guideline and associated education, serving as our annual organizational competency to meet The Joint Commission standards.12

Rationale

Although therapists are educated on cardiovascular risk factors and trained to assess vital signs, there has been a well-documented lack of monitoring in outpatient clinics.13,14 Reported barriers to monitoring include the perception that it is “not important for my patient population,” lack of time, and lack of appropriate equipment. Our organizational leadership supported a plan to institute a meaningful and reasonable guideline to improve the monitoring of outpatient vital signs (e.g., heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation). With multiple stakeholder involvement, we formed consensus around assessing vital signs on every new patient during initial evaluation. Using the cardiovascular risk profile of the patient as a guide, stratified follow-up monitoring was performed, such that the more risk factors present, the more monitoring recommended. As hypertension is a global problem that can be effectively treated with early detection, blood pressure assessment emerged as having the greatest potential impact on overall patient health and safety. Thus, the specific intent of detecting dangerously high blood pressure in an otherwise asymptomatic individual became a primary focus of this project work.

Aim

Our goal was to institute a guideline on vital sign monitoring across our organization’s entire outpatient therapy service line to optimize patient safety, with the focus on increasing detection of dangerously high blood pressure.

Objectives

-

All outpatient therapists complete the Vital Sign Guideline education and annual competency within a six-month period.

-

All new patients have vital signs assessed during the initial evaluation, regardless of primary diagnosis, age, or medical history.

-

When therapy is stopped, or not initiated due to vital signs outside of the guideline parameters, appropriate action is taken, including but not limited to submitting an incident report; contacting the primary care provider; recommending going to the emergency room; and, if necessary, calling 911.

-

Appropriate documentation in the medical record reflecting blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation monitoring, and action taken.

Methods

Interventions

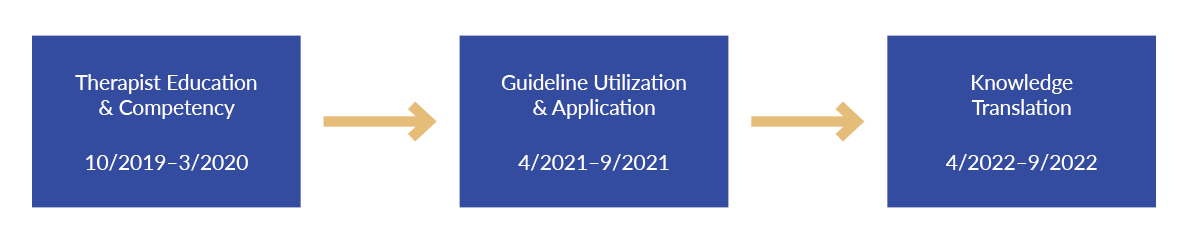

The interventions were studied in a phased approach over a three-year period (Figure 2) and followed the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) framework. To ensure project success, the implementation and sustainability was too expansive for one or two project leaders. Thus, stakeholders were engaged from across the organization and included outpatient site managers, therapists, therapy administrative leadership, physician leaders, and the director of Patient Safety, Risk and Regulatory Affairs.

Phase I: Guideline Development, Staff Education, and Safety Champion Selection

As no organizational guideline existed for outpatient therapists on the monitoring of vital signs, project work started with a review of the literature. While the literature search confirmed a lack of vital sign assessment in outpatient therapy practice, no specific interventions or guidelines were published for implementation. Recognizing this gap, the literature was reviewed again for best practice around medical screening to use as a foundation for the organizational guideline. The guideline included normal and abnormal ranges for heart rate and blood pressure, and an algorithm to guide action when abnormal values were detected at baseline and with activity. The guideline was reviewed by various stakeholders for consensus and approved by our organization’s Medical Executive Committee.

Implementation of the guideline was supported by therapist education and competency assessment. Baseline education was developed to ensure therapists were adequately trained in three main concepts: the importance of monitoring every new patient, the rationale for monitoring based on risk factors, and appropriate action to take based on patient presentation. Competency assessment focused on ensuring therapists could demonstrate proper vital sign assessment, verbalize use of the guideline, and determine appropriate next steps. Safety champions at each outpatient location were designated as the owner of the process. Each safety champion was educated on the guideline, competency, and protocol. This allowed the safety champions to serve as the competency validator and own the responsibility for competency completion for all therapists in their clinic. The competency served as our annual organizational competency and completed competencies were maintained in a centralized location by the site managers to demonstrate compliance with The Joint Commission standards.

Site safety champions were key to ensuring clinics had the appropriate equipment, such as manual and electronic blood pressure cuffs and stethoscopes, in order to monitor vital signs adequately. Safety champions were surveyed regarding type of equipment in use at each clinic, the cost, staff satisfaction, ease of use, and reliability of blood pressure assessment. This information was distributed to the outpatient managers with recommendations made based on budget, need to support patient monitoring, and standardization across sites.

Phase II: Evaluation of Guideline Implementation

The second phase of the project assessed whether the guideline was utilized and applied correctly. To determine this, a quarterly event report review process was implemented. Every event report in the “change in medical condition” category was reviewed to determine whether it was applicable to the guideline and if so, determine whether it was followed correctly. While event reporting can typically reflect patient harm, in our project an increase in event reporting was expected. For example, with guideline implementation, therapists can identify unknown conditions of elevated blood pressure in patients presenting for therapy. When an abnormal blood pressure is identified, therapists are expected to provide appropriate action and document the finding in an event report. Thus, appropriate utilization of the guideline would result in a concurrent increase in event reporting. A multipronged approach was used for communicating quarterly event report data to our stakeholder groups and included outpatient manager meetings, safety champion updates, clinical site huddles, and quarterly quality committee meetings. Quarterly event reports (excluding clinic closures due to the COVID pandemic) were compared before and after implementation of the guideline.

Phase III: Assessment of Knowledge Translation

The final phase of the project focused on knowledge translation as evidenced by documentation of vital signs in the patient’s electronic medical record. To ensure appropriate translation of knowledge to practice, we integrated this project with a concurrent therapy chart audit project. A question asking whether vital signs were documented was added to the chart audit form and chart reviewers were instructed on the expectation to assess vital signs on every new patient. Chart audit data revealed an immediate opportunity to convert the vital sign field to a mandatory field, which placed a hard stop in the electronic medical record unless vital signs were documented.

Study of the Interventions: Outcome Measures

Varying outcomes were measured in each phase of the project. In Phase I, the percentage of outpatient therapists successfully completing the education and competency in the six-month period was measured. The completion percentage was calculated by determining the number of outpatient therapists employed as compared to those who completed the competency. In Phase II, “change in medical condition” events were reviewed using pre-specified criteria to determine correct use and application of the guideline and compared to the pre-project period. Submissions documenting an acute decompensation were not included in the scope of this project. In Phase III, annual chart reviews were analyzed to determine whether therapists assessed and documented vital signs, reflecting translation of the guideline education into clinical practice.

Analysis

In Phases I and III, descriptive statistics were used to report outcomes. In Phase II, the number of guideline-appropriate events and percentage correctly applied was compared in a six-month period before (fiscal year 2019 Q4 and fiscal year 2020 Q1) and six-month period after (fiscal year 2022 Q3 and fiscal year 2023 Q1) project completion. In Phase III, chart reviews were used to assess knowledge translation in a six-month period spanning FY22 Q4 and FY23 Q1. Student’s t-test compared before and after guideline-appropriate events, with a p-value less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

All outpatient therapists (N=185) completed the guideline education and competency within the expected six-month time period. Eighty-three therapists (45%) completed the requirements to obtain one contact hour towards Pennsylvania therapy licensure.

There was a 1,000% increase in the number of medical events applying the guideline reported across outpatient clinics, from six in the period preceding implementation to 66 at project completion (Figure 3). This increase was found to be statistically significant as determined by a Student’s t-test (p-value=0.02). Except during the COVID-19 pandemic outpatient clinic closures, there was an incremental increase in guideline-applicable medical events reported over the project duration, with the run chart demonstrating the incremental increase in events reported as changes were tested (Figure 3).

Prior to project implementation, only six events were reported. An increase in event reporting was demonstrated over the project phases and therapists correctly applied the guideline 95% of the time after Phase I, 92% after Phase II, and 94% upon project completion in year three.

An audit of the FY22 (July 2021–June 2022) chart reviews found 317 out of 474 (67%) of charts documented vital signs. Of the 157 charts without vital signs documented, most were orthopedic patients (N=106, 68%). (See Table 1.)

Summary

There was a statistically significant increase in the number of medical events reported after guideline implementation. Six events were reported prior to the project, incrementally increasing each subsequent year. To date, results continue to be sustained, with therapists correctly applying the guideline on average 93% of the time over a two-year period. There remain opportunities to improve the translation of this knowledge into practice as seen within the documentation reviews, especially in the orthopedic patient population.

Interpretation

This project developed and implemented an evidence-based vital sign guideline where none had previously existed. The project was able to sustain the education and competency with a 100% completion rate, and the guideline is now included in the new employee onboarding competencies. However, we discovered completion of education and competency alone did not directly imply the translation of knowledge to practice occurred. Integration within the electronic medical record was essential to drive improvement.

The goal was to improve the consistency of vital sign monitoring by instituting a guideline across our organization’s entire outpatient therapy service line to optimize patient safety by increasing detection of dangerously high blood pressure. We hypothesized implementation of the guideline would result in an increase in event reporting, as asymptomatic vital sign abnormalities were detected. We found a significant increase in reporting as anticipated. Review of the event reports confirmed patients were educated on the rationale for vital sign assessment, significance of the values, and recommendations for follow-up.

There were several key factors contributing to project success. First, engaging safety champions as change agents at each outpatient clinic was an integral factor in changing practice across all 25 clinics. Safety champions shared data, discussed barriers, and explored strategies for success with the project leader and one another to understand issues preventing utilization and/or application of the guideline. As clinics were located across a widespread vicinity, the safety champions served as the boots on the ground resource for the project leader. The value of the site champions as change agents cannot be understated, and this is now a key component integrated into all quality projects.

Another factor contributing to project success was the multifaceted approach to data review and reporting. Qualitative review of incident reports served as a catalyst to drive overall project direction and keep patient safety in the forefront throughout the project. Managers, senior leaders, and the organization’s quality committee received quarterly updates on project work. Safety champions and managers discussed project work and data at site huddles to further drive change to practice.

As an organization committed to becoming a high reliability organization, this project was able to leverage the strong culture of patient safety already in existence. Our organization’s tiered huddle structure provided the forum to display this quality project data, discuss it, and obtain improvement suggestions from frontline employees. Therapy leaders, managers, and therapists were engaged throughout the project and safety champions stepped up to lead site work. Patient engagement was addressed by having therapists educate patients on the rationale for vital sign assessment and appropriate follow-up. A therapist was recognized as part of the health system’s annual patient experience week for identifying a serious abnormal vital sign finding in a patient and properly referring for care, further validating the value of the project.

Limitations

Limitations included challenges around data accuracy and limited real-time data to drive change. As we were unable to extract blood pressure documentation directly from the electronic medical record or implement documentation prompts, the project relied on event reporting data to indirectly measure guideline utilization and application. Thus, there is the potential for underreporting of events or incomplete event information. The project also relied on therapist acceptance of the importance of assessing vital signs, even in a young, healthy athlete.

There are several opportunities for ongoing improvement. In events where the guideline was applied, it would be useful to determine whether the patient returned with new activity parameters, whether medications were adjusted, and/or whether medical intervention was required. We recommend additional efforts targeted to specialty areas having high documentation deficiencies, such as orthopedics. Leveraging the electronic medical record to provide clinical prompts to document blood pressure also has the potential to improve translation of the guideline into clinical practice.

Conclusions

The goal of this project was to implement an outpatient therapy vital sign guideline for exercise and physical activity to ensure a patient’s safe participation in the plan of care. By substantially increasing vital sign monitoring in all outpatient therapy clinics, we were able to proactively identify known or unknown abnormalities to prevent more serious events from occurring. Using a multiphase plan, this project implemented an evidence-based guideline into practice, resulting in a positive impact on patient safety in the ambulatory setting.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Good Shepherd Penn Partners leadership team, including Sandy Neubauer, MBA (assistant vice president, Outpatient Therapy), and Nina Renzi, BSN, RN (director of Patient Safety, Risk and Regulatory Affairs), for supporting this project from initial concept to completion. Special thanks to Brian Leggin, DPT, PT, and Bill Pino, DPT, PT, for data assistance. The authors would especially like to acknowledge the outpatient therapy site managers, site safety champions, and therapists for the collaboration and steadfast commitment throughout the entire project.

Contributors

The Patient Safety Authority helped guide the initial draft of this manuscript.

Funding

There was no external funding for this project.

Ethics Review

The University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined this project qualifies as a quality improvement initiative that does not meet the definition of human subjects research. No IRB review was required.

About the Authors

Joe Adler (joe.adler@pennmedicine.upenn.edu) graduated in 1993 with a Master of Science in physical therapy from Arcadia University (then Beaver College) in Glenside, Pennsylvania, and earned a transitional doctorate in physical therapy from Arcadia University in 2011. He has worked at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia since graduation. He spent the first three years testing the waters of outpatient and inpatient acute rehab but found his passion in acute care in 1996 and has never looked back.

Jennifer Dekerlegand obtained her bachelor’s in health sciences and master’s in physical therapy from the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science (now University of the Sciences in Philadelphia). Dekerlegand has been employed by Penn Medicine/Good Shepherd Penn Partners for over 25 years, and she currently serves as the director of Research, Education and Quality. Dekerlegand is certified in healthcare research compliance (CHRC) and is a lean management practitioner.