Introduction

Problem Description

The University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS) Clinical Practices of the University of Pennsylvania (CPUP) ambulatory practices experienced an increase in patient falls in 2021, including a serious fall resulting in harm to the patient. Falls in ambulatory clinics are multifactorial and screening does not occur until a patient has already spent a significant amount of time in the setting, increasing the risk of these events. It is unclear if patients who were previously identified as a falls risk, either inpatient or at another visit, were aware of their risk, and if they had action taken such as physical therapy consults, home evaluations, or medication review. It is also unclear if ambulatory providers were aware of the falls risk of patients they see in clinic.

Setting

UPHS is a major, multihospital health system headquartered in Philadelphia.1 CPUP clinics span across the Delaware Valley and ambulatory providers complete more than 2.4 million patient visits annually. This falls-focused improvement effort was piloted in an outpatient Neurology clinic in November 2021. This clinic completes on average 6,500 patient visits per month.

Available Knowledge

A fall is defined as “a sudden, unintentional descent, with or without injury to the patient, that results in the patient coming to rest on the floor, on or against some other surface (e.g., a counter), on another person, or on an object (e.g., a trash can).”2 In the ambulatory setting, patient falls are limited to the time between check-in for a visit and checkout from a visit. Falls that occur before and after a visit are considered visitor falls and are not included in the interventions or data set.

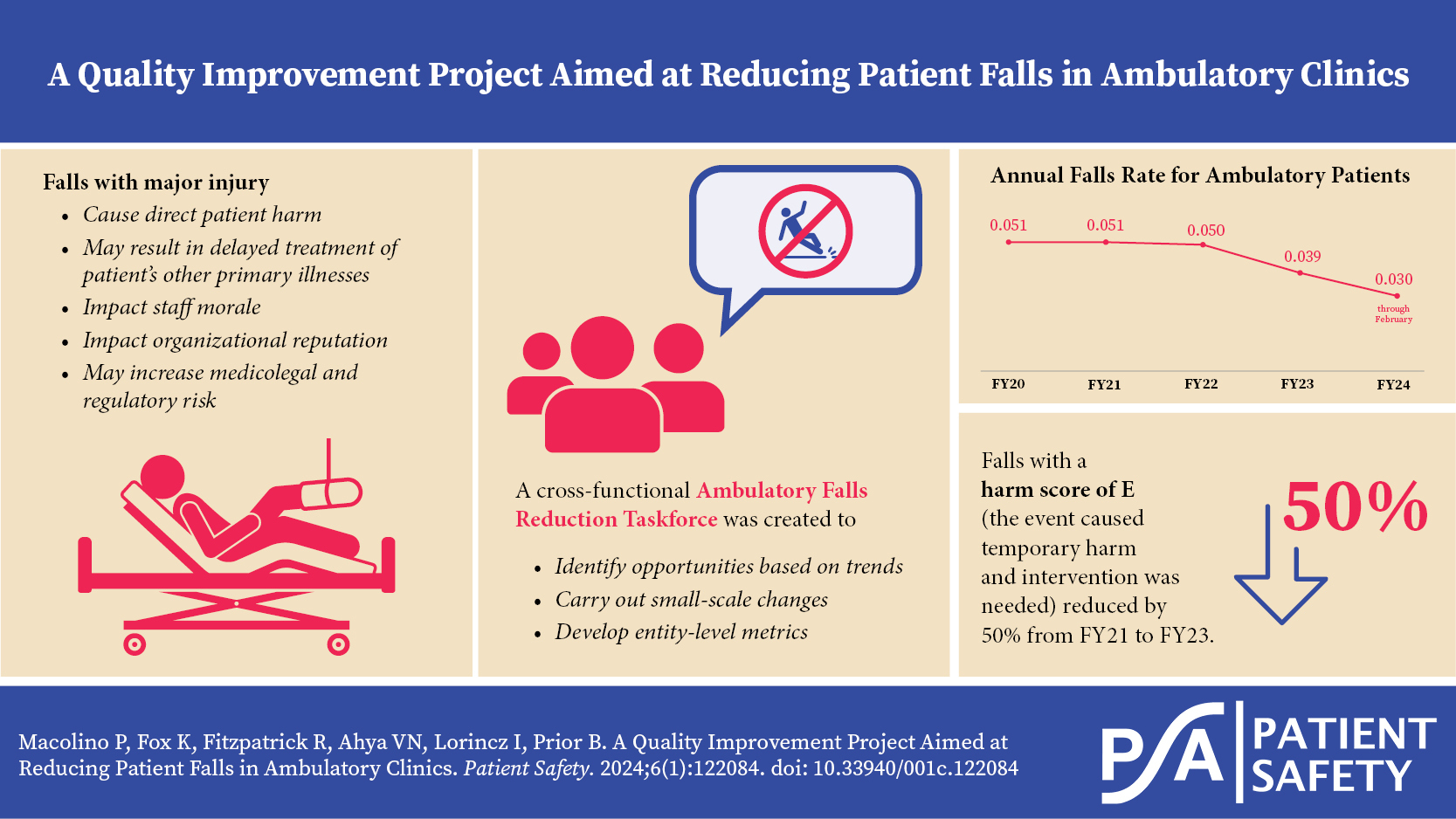

Falls with major injury are those resulting in a fracture, surgery, casting, or traction requiring consult/management or comfort care for a neurological injury (e.g., skull fracture, subdural, or intracranial hemorrhage) or internal injury (e.g., rib fracture, small liver laceration), or resulting in death or permanent harm as a result of injuries sustained from the fall (not from physiologic events causing the fall). In fiscal year (FY) 2022, there were 10 patient falls that required an intervention ranging from sutures or splinting to observation, and three patient falls that required hospitalization. Falls with major injury not only cause direct patient harm, but also may result in delayed patient treatment of other primary illnesses, as well as impact staff morale, organizational reputation, and potential medicolegal and regulatory risk.

Screening for falls risk includes two Medicare wellness survey questions, “Have you fallen more than once in the past year or hurt yourself in a fall?” and “Do you feel you are at risk for a fall?” Both questions are subjective and although they are known predictors of future falls and evidence-based, they lend themselves to bias and denial by patients. In a literature search, it was found that other than the Medicare wellness survey, there is no valid and reliable screening instrument for ambulatory patients. Patients’ visits are limited and time constrained, often with specialists, not with their primary care provider.

Rationale

Changing the falls screening was in part driven by a sentinel fall in March 2021. The Joint Commission defines a sentinel event as “a patient safety event that reaches a patient and results in death, permanent harm, or severe temporary harm” or intervention is required to sustain life.3,4 A patient was injured, and during root cause analysis providers indicated that they were unaware of the patient’s risk of falling.

The initial solution identified during the root cause analysis was to add a third question to the falls screening rather than replacing a question. The decision to instead change the subjective question to an objective question was based on feedback from practice staff who recommended including an evidence-based question that would be more reliable in the identification of falls risk and prompt action by staff. The updated objective question was pulled directly from the Morse falls risk screening tool5 and is currently being used in the inpatient setting. The use of an assistive device can be visually verified, reducing risk for subjectivity and increasing efficiency of screening.

The updated falls screening better captured a patient’s risk for falling and provided an opportunity to employ preventive measures to avoid falls and falls with injury.

Aim

To redesign the falls screening process and falls screening questions with actions to take if a patient screens positive, and to reduce falls by 10% by end of FY23.

Methods

Context

This is a quality improvement project that uses improvement methodology to test and implement change strategies.

Interventions

The improvement team was made up of a cross-functional group of subject matter experts from the health system. This team included quality and safety personnel, nurses, physicians, advanced practice providers, electronic medical record (EMR) project strategists, and departmental operational leaders. The team identified gaps in screening and communications processes and opportunities by reviewing the output of a sentinel fall root cause analysis; it was discovered that the screening process was vulnerable to failure and did not have a clear communication and prevention process in place. The screening questions were not objective and failed to capture other more immediate and obvious risk factors.

Prior to receiving the falls screening questions in clinic, patients were sent a one-way text message emphasizing the need to wear comfortable shoes, bring their assistive device, and bring a support person if they need help changing or traveling. After the visit, patients were sent two custom questions to confirm if they received the message and read the message.

One of the two original Medicare wellness survey falls screening questions was changed: “Do you feel you are at risk for a fall?” was replaced by “Do you use a cane, walker, wheelchair, or furniture to get around?” The first question, “Have you fallen more than once in the past year or hurt yourself in a fall?” remained the same. A “yes” to either question triggers the addition of an FYI Falls Risk flag in the EMR and prompts the clinical team to offer the patient assistance with toileting, transferring, and changing.

An EMR system smart phrase was created to document patient education for fall prevention on the patient’s After Visit Summary (AVS) when warranted. This smart phrase populated information in the AVS about reducing the risk of falls at home and making the home environment “fall-proof.”

Study of Interventions

To evaluate the performance of the interventions, data was collected from the patient safety event reporting system on the number of patient falls, the number of patient falls with injury, the rate of patient falls, and the rate at which falls risk questions were asked as a part of the health screening survey for patients over the age of 65.

After implementation of the interventions, data was collected for 32 days before analysis and adjustment. Feedback was also gathered from clinic users and patients. Twenty-nine staff members from the pilot clinic were surveyed after implementation; this group consisted of physicians, advanced practice providers, nursing staff, and medical assistants.

Best Practice Advisory (BPA): Of the population surveyed, 76% of respondents either had not seen the BPA fire or ignored the BPA that indicated that a patient was at risk for falling. Eighty-three percent of survey respondents indicated that presence of the falls risk BPA or falls risk flag did not change the care they provided the patient. Data collected on the utilization of the best practice advisory showed very little engagement by providers. Based on the low level of engagement and action, the BPA was decommissioned in November 2022.

Pre-Visit Communication to Patients: Patient feedback via electronic survey from the pilot group showed that of the 271 patients who acknowledged that they received the pre-visit communications, only 8% modified their preparation for the visit. Eighty percent of respondents did not change how they prepared for their ambulatory visit.

Fall Risk Screening: After broad implementation of the new falls risk screening question and EMR changes across all ambulatory settings showed minor improvement in the monthly falls rate (falls rate flat from October 2021 to February 2022), the Ambulatory Falls Reduction Taskforce was created. The taskforce is a cross-functional group of both clinical and nonclinical subject matter experts from ambulatory and inpatient departments. Problem-solving was completed and updated areas of focus were identified. Importantly, the taskforce developed a standard dashboard and set of metrics to guide in making data-driven decisions.

Event Reporting Debrief: With the help of safety event data and the implementation of a post-fall debrief, the team was able to identify opportunities such as increasing wheelchair availability for patients and improving pre- and post-visit communication about falls risk. The team also identified a gap in the completion of the falls screening questions in clinic, an area for continued focus and improvement.

Measures

Patient falls and patient falls with injury were the primary outcome measures for this intervention. The data source for this measure was the UPHS safety event reporting system, Penn Medicine Safety Net. Data was validated by doing manual chart reviews when patient falls occurred.

A secondary outcome metric was the patient fall rate, calculated by dividing the total number of patient falls for a time period (month and year) by the total arrived in-clinic encounters for a time period (month and year). This normalizes the number of patient falls for a given clinic or division.

Analysis

The data for the intervention was analyzed by using statistical process control and standard run chart rules.

Results

While the change in falls risk screening questions and supporting EMR functionality made only small improvements from FY21 to F22 (2% decrease in falls rate), it led to an increased focus on falls reduction and the identification of fall risk for patients and resulted in the development of the Ambulatory Falls Reduction Taskforce. The falls rate for ambulatory patients fell from 0.050 in FY22 to 0.039 in FY23, a 22% reduction (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The falls rate for ambulatory patients has continued to decrease; the current annual falls rate for FY24 is 0.030 through February, a 37% reduction from FY21 rate 0.051.

Additionally, a reduction in high harm score falls was realized. Falls with a harm score of E (the event caused temporary harm and intervention was needed) reduced by 60% from FY22 to FY23, and falls with a harm score of F (the event caused temporary harm and hospitalization was needed) stayed the same at 3 falls each for FY22 and FY23 (Figure 7). There were no patient falls that resulted in permanent harm, near death, or death.

Discussion

Summary

The evidence-based change of falls risk screening questions, as well as supporting EMR changes and the development of the falls reduction taskforce, resulted in a moderate reduction in the falls rate for ambulatory patients. This change has been sustained by the use of staff standard work, monthly measurement, and continued focus on reducing the risk of patient falls.

A cross-functional falls taskforce was assembled in November 2021, with a focus on data-driven interventions at all steps of the patient visit. This taskforce has continued to find opportunities for formal and informal improvements. Among other interventions discussed earlier in this manuscript, the CRADLE acronym was developed and introduced as a multifaceted approach to managing patients at risk for falling. CRADLE stands for:

Interpretation

The overall reduction in falls rate from FY22 to FY23 shows a reduction in patient falls greater than our aim of 10% and an increased awareness of patients who are at risk of falling, leading to targeted interventions.

Limitations

Medical assistants are accountable for screening patients, but providing education, tip sheets, etc. is outside their scope. Provider burnout and BPA fatigue were identified as contributing factors to low uptake on the Best Practice Advisory, which was designed for providers to take action for at-risk patients.

Falls risk screening occurs during the rooming process, further downstream in the patient visit. Patients previously identified as being at risk for falling have no intervention prior to subsequent clinic visits and the ambulatory falls risk flag does not interface with the inpatient EMR.

As mentioned in the Abstract, outpatient falls are unique; patients who come for office visits are unfortunately confronted with additional fall risks (parking garages, elevators, escalators, hallways, etc.) that can’t necessarily be avoided. Ambulatory visits are typically limited to 30–60 minutes, which does not always allow the time needed for providers to discuss falls risk and prevention with patients.

Falls risk screening questions are not required at all ambulatory visit types; laboratory sites do not routinely screen for falls risk and Radiology screens for risk but uses an internal screening tool that does not interface with the health screen tool, where the FYI flag is automated for a positive screen. This variation in practice creates a challenge for both patients and staff.

Screening data is limited to patients over 65 years old and completed by the medical assistant. We are working on abstracting data for patients 18 or older and screening completed by any member of the care team. The safety event reporting system we use does not interface with the EMR; patient charts are randomly audited, but ideally there would be a direct interface between an at-risk patient who fell and what interventions were in place with the safety event reporting system. The safety event reporting system is user defined and inputs are not always validated.

Falls risk screening is only completed in face-to-face encounters and is thus excluded from telemedicine visits. The patient safety reporting system is limited to collecting data pertinent to the inpatient environment; we introduced a survey tool to capture variables applicable to an ambulatory fall, such as footwear and physical environment at the time of the fall. We also encourage staff to contact our Employee Assistance Program if they are experiencing second victim syndrome following a near miss event or an event that reached the patient and led to harm.

Lastly, there is no comparison group, and it is impossible now to analyze the rate at which patients are identified to be at risk of falling with the updated falls screening questions versus the original falls screening questions.

Conclusions

Using data and industry best practice to modify the falls risk screening questions resulted in better information from patients and thusly more accurate screening of falls risk. Building falls prevention into the daily work and responsibility of all staff allowed for further expansion of the falls reduction work and sustainment of interventions.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the CPUP Neurology team who were willing and enthusiastic participants in the pilot of the updated falls screening questions and associated interventions. Without their time and feedback, this patient-focused safety improvement would have been much more challenging.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

About the Authors

Patricia Macolino (patricia.macolino@pennmedicine.upenn.edu) is the director of Quality Ambulatory Care for the Clinical Practices of the University of Pennsylvania (CPUP), Penn Medicine. She is a registered nurse and a certified Lean Six Sigma Green Belt, and she earned her Master of Science in nursing at Walden University. Additionally, she is a Certified Professional in Healthcare Quality and acts as an instructor for courses within the Center for Healthcare Improvement and Patient Safety.

Katie Fox is a master improvement advisor at the Clinical Practices of the University of Pennsylvania (CPUP), Penn Medicine. She earned her Master of Business Administration from Temple University and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt certification from Villanova University.

Rebecca Fitzpatrick is a regulatory affairs consultant at Penn Medicine. Previously, she was a clinical director at the Clinical Practices of the University of Pennsylvania (CPUP). She earned her Master of Science in nursing at Georgetown University and doctorate of nursing practice at Jefferson.

Vivek N. Ahya is the chief medical officer for the Clinical Practices of the University of Pennsylvania (CPUP), Penn Medicine. Dr. Ahya is an associate professor of Medicine (Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care) at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP). He was trained at the Boston University School of Medicine and received his Master of Business Administration from the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School.

Ilona Lorincz is the patient safety officer for the Clinical Practices of the University of Pennsylvania (CPUP), the director of quality for Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP), and an associate professor of Clinical Medicine of the Perelman School of Medicine. Dr. Lorincz was trained at the Georgetown University School of Medicine and received her master’s in health policy research from the University of Pennsylvania.

Barbara Prior is the associate executive director of the Clinical Practices of the University of Pennsylvania (CPUP). She received her Bachelor of Science from The College of New Jersey and her Master of Science in health leadership from the University of Pennsylvania. Prior is board certified as a nurse executive by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC). She is an active member of American Organization of Nurse Leaders (AONL), American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing (AAACN), and the American Nurses Association (ANA).

.jpeg)

.jpeg)