Introduction

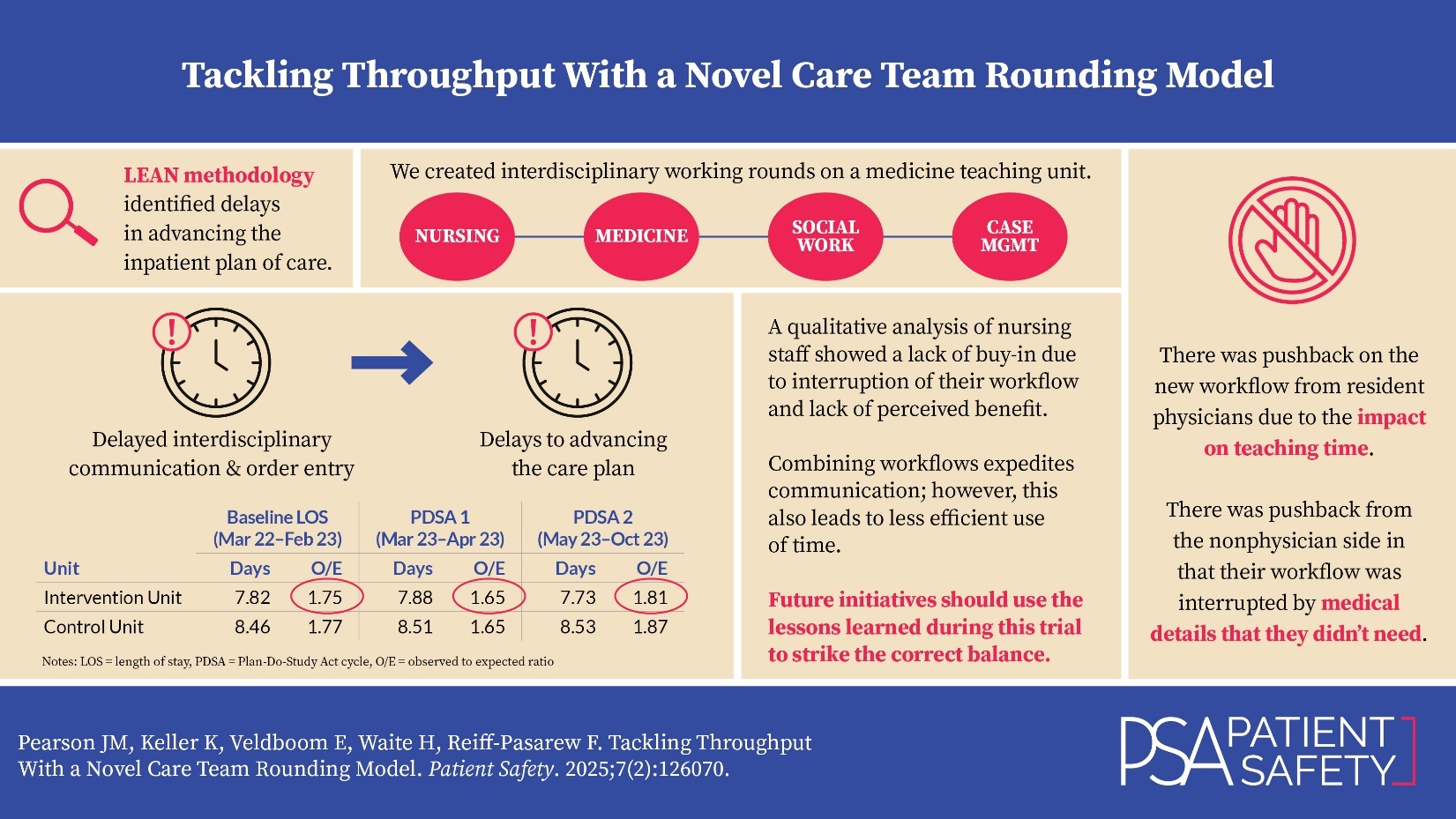

The quality team and unit leadership at Mount Sinai Morningside (MSM) hospital observed increased length of stay (LOS) among medicine patients. On one medical-surgical unit that was used as the intervention unit for this initiative, the baseline LOS from March 2022 to February 2023 was 7.82 days with an observed to expected ratio (O/E) of 1.75. The expected LOS is the predicted inpatient stay determined by a proprietary risk adjustment methodology developed by Premier Inc. health analytics platform based on patient characteristics and admitting condition. The quality team and unit leadership committed to identifying the causes of excess patient days as a hospital priority.

Improving LOS is essential to decongesting hospitals and maintaining financial viability. Insurance payers reimburse hospitalizations based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). When LOS exceeds the expected value, hospitals may incur more costs in providing care than are reimbursed. The impact of LOS on hospital expenses is substantial. A recent study that reduced in-hospital LOS by addressing factors associated with delays in patient care, including hiring additional physicians (MDs) and mid-level staff, found that a significant decrease in LOS led to improved costs despite the expenses associated with additional staffing.1 Administrative factors such as enhancing hospital management processes for patients with multiple diagnoses and severe conditions also improve LOS2; however, they often require large hospital or even systemwide approaches to implement.

Interdisciplinary rounding provides a unit-level approach to decreasing LOS. A systematic review of the effects of interdisciplinary rounding on quality of care and team collaboration demonstrated that rounding could improve LOS.3 A study from 2019 found that implementing team-based multidisciplinary rounds significantly improved discharge efficiency, including reducing LOS.4 The importance of effective communication and collaboration in the discharge process was emphasized as having the largest impact on LOS.4 Interdisciplinary rounds that promote physician initiative and early nursing participation improve communication and quality of care.5

The Lean methodology of quality improvement (QI) uses a set of instruments to identify waste, improve efficiency, and support a philosophy of continuous improvement.6 Mangum et al. used Lean principles to identify an opportunity to improve throughput by earlier discharge order entry, increased situational awareness by team members using a dashboard, and improved efficiency to relocate printers to the point of use.7 After implementing these interventions, LOS decreased by nearly one day.7

The purpose of the QI initiative described here was to utilize the Lean methodology to develop more comprehensive interdisciplinary care team rounds to improve efficiency in communication and initiation of the care plan and ultimately improve hospital throughput.

The primary aim of this QI initiative was to decrease LOS by one day from the start of the QI initiative over a six-month period. A secondary aim was to improve communication and workflow as reported by the care team. The process measures were improved perception of communication and efficiency by the staff, which was evaluated through an electronic survey and a qualitative focus group.

Methods

This QI initiative took place at Mount Sinai Morningside (MSM), an academic medical hospital which has 495 certified beds and is a member of the Mount Sinai Health System. The MSM hospital discharges approximately 14,000 patients annually, accounting for 97,000 days of patient care. The average occupancy rate is 82% with a hospitalwide average length of stay of 5.8 days. The hospital is in the Morningside Heights neighborhood and draws patients primarily from Morningside Heights, Manhattan Valley, Harlem, and the Upper West Side of New York City.

The unit implementing the QI initiative is a 29-bed medical-surgical unit with a nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:5 and two patient care associates. A geographically located medicine teaching team led by an academic hospitalist attending covers half the unit. This geography enabled the teaching team to trial interdisciplinary care team rounds.

Intervention

The hospital’s Lean lab led a value-stream mapping (VSM) exercise to examine opportunities to improve throughput. VSM is a Lean tool that visualizes a current process (including the flow of materials and information) and identifies improvement opportunities, such as reduction of waste. Representatives from all disciplines across the hospital mapped out a patient from admission to discharge in granular detail. Value stream mapping typically includes more detailed information than process mapping, such as the time to complete each step. The participants in the exercise used that start point of admission and conducted a step-by-step analysis of advancing the care plan to the endpoint of discharge.

Areas of opportunity to improve throughput that were identified through the value stream mapping exercise included initiation of the plan of care earlier in the day and improvement in interdisciplinary communication in real-time about the plan of care. A patient’s plan of care during the acute phase of their inpatient stay requires assessment and reassessment of the patient’s needs. Communication about the plan can be disjointed and result in the care team (nurses, social work, case management, providers) being misaligned. Communication about and initiation of the patient care plan for the next 24 hours to all members of the care team early in the shift is not consistent. The baseline workflow did not encourage entering orders prior to interdisciplinary rounds (IDRs), which delayed progressing the plan of care and contributed to excess days. In the pre-intervention state, IDRs were held from 10:30–11 a.m. at the nursing station with case manager (CM), social worker (SW), unit medical director (UMD), nurse manager (NM), physical therapist (PT), and charge nurse. Each team would send a representative to present a one-line update on their patients, followed by a brief conversation regarding any challenges and anticipated discharge needs. The bedside nurses were not present. Often planned orders would not be placed until after IDRs.

Key stakeholders actively participated in a Lean methodology Kaizen workshop led by a facilitator to develop the QI initiative. The Kaizen workshop was a three-day process that involved going to the location where the process takes place to observe what is happening and who is present. In Kaizen workshops, after this initial observation participants also go to another location to be creative and see how the process is done somewhere else. For this exercise, the quality team and unit leadership went to the intensive care unit (ICU), where interdisciplinary, bedside rounds are routine and involve real-time problem solving of issues identified.

During the workshop, the team identified areas of opportunity to improve the IDRs process and employed creative thinking, problem solving, data collection, brainstorming, and implementation of improvements. The event included representation from physician and nursing unit leadership, the medical residency, social work, physical therapy, case management, and nursing. The goal of the workshop was to create a process that enabled the entire interdisciplinary care team to know the plan of care for an integrated start to the day. The hope was to minimize multiple bilateral conversations throughout the day (often via Epic electronic medical record secure chat) in favor of a multilateral conversation early on.

Baseline State: January–March 2023

The rounding process prior to this initiative is illustrated in Figure 1. The resident physician staff would round in a workroom on the unit between 9 and 10:30 a.m. with the attending physician on the team. The physician team typically visited new patients at the bedside together, and other patients as needed per the attending physician preference. When physician rounding and teaching was finished, a representative of the physician team would join the interdisciplinary rounds with the remaining care team members between 10:30 and 11 a.m. Often the physician team would need to reconvene to complete discussing patients at 11 a.m.

The social work team arrived between 8 and 9 a.m. and reviewed their patients’ cases, including any events overnight that might influence planning. They visited patients at the bedside as needed. Social workers attended interdisciplinary rounds from 10:30 to 11 a.m. Case managers arrived at 9 a.m. and joined interdisciplinary rounds after reviewing their cases. Frontline nursing staff was not present during rounds as they were providing patient care. However, one to two nursing representatives, a nurse manager and/or a charge nurse, were present during rounds to communicate reports from the nurses and to report to them afterwards.

During the baseline state, the resident physicians did not see most patients at the bedside as a team (newly admitted patients were seen at the bedside). Additionally, the bedside nursing staff did not attend IDRs and communicated via nursing representatives.

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Cycle 1: March–April 2023

The first iteration of care team rounds (CTRs) addressed several gaps identified during the Kaizen workshop, including (1) delay/lack of communication between physician and nursing staff on care plan, and (2) delay in discharge orders being placed until after IDRs for confirmed discharges. Interdisciplinary CTRs, including staff nurses, started earlier in the morning to address the delay or lack of communication between the physician and nursing staff. To address the inefficiency of delayed discharge orders, the care team utilized three workstations on wheels (WOWs) to place orders, including discharge orders, in real time during rounds (Figure 2).

This iteration of CTRs involved walking bedside rounds that included the primary physician team, physician and nursing unit leadership, social work, case management, and nursing. The leader of the rounds was the attending physician, and the first intern presented the patient. The second intern placed orders utilizing the WOW. The primary nurse was available to provide an update on events overnight. While the care team was at the bedside, they would conduct a brief patient exam and share the plan with the patient. These rounds were intended to replace the “working rounds” for the primary medical team that were previously held in the workroom. If the patient was approaching discharge, the case manager and social worker were available to answer questions. Each patient’s rounds concluded when every team member became aware of the plan and answered all questions (Figure 2).

The quality team elicited feedback by directly speaking with participants in the CTRs. During these conversations, the team took notes to accurately record feedback (Table 1). Some of the positive feedback was that team members felt they “got clarity on the plan” and had “more time to ask questions [this way].”

In addition to the feedback obtained in Table 1, the care team identified opportunities to incorporate updating the patient care boards and also standardizing the method for introducing team members.

PDSA Cycle 2: May–October 2023

Findings from the first PDSA cycle showed that bedside CTRs were compromised by distractions, which contributed to missed information. The quality team modified the second iteration of CTRs and moved the rounds to a nursing station located in the middle of the unit to reduce distractions and improve communication. Conducting CTRs at the nursing station also allowed case management and social work to have access to a computer and phone so that time-sensitive coordination could occur. The start time of CTRs was changed from 9 a.m. to 9:30 a.m. to allow registered nurse (RN) morning medication pass (Figure 3). The clinical team conducting CTRs called the primary nurse assigned to the patient into rounds by their assigned district of patients. In this model, the care team saw patients at the bedside only as needed.

In this iteration of care team rounds, there was less wasted time and fewer distractions. In addition, the participants required less direction and oversight to keep the rounds moving forward, which allowed rounds to finish faster. Participants also reported improved communication with bedside nurses, case management, and social work. This iteration maintained real-time order entry and team problem solving while addressing the concerns raised during the first PDSA cycle. Ultimately, the medical team chose to see very few patients together at the bedside.

Measures

Primary Outcome Measure: Length of Stay

The quality team measured LOS by obtaining the number of days of hospitalization from hospital administrative data for patients discharged by physicians who cared for patients on the intervention unit. The baseline LOS from March 2022 to February 2023 was 7.82 days with an O/E of 1.75. The baseline period was selected as the calendar year prior to the intervention to account for seasonal variation in the average LOS.

Process Measure: Non-Nursing Staff Survey

The quality team separately measured the staff perception of the care team rounds. For non-nursing staff, including resident physicians, attending physicians, case management, and social work, an anonymous survey was distributed electronically in October and November 2023 (Appendix A). The survey contained questions regarding their experience with the new care team rounds as well as an opportunity to enter free-text comments.

Process Measure: Nursing Focus Group

To better understand the impact of the CTRs on the nursing staff, the quality team held a 45-minute qualitative focus group in November 2023. The quality team asked nurses questions about their experience of CTRs using a semistructured interview format (Appendix B). The quality team held the focus group during a regularly occurring staff meeting in the morning between day and night shifts. A member of the quality team not involved in patient care on the unit conducted the focus group to allow the staff to voice their opinions without influence from unit leadership. The study team decided not to record the focus group to allow the nurses to speak freely, and a second member of the quality team took notes during the focus group.

Secondary Outcome Measure: Patient Satisfaction

The quality team used the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey (HCAHPS), developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service (CMS), to measure patient satisfaction. The “Overall Hospital Rating,” “Staff Worked Together – Teamwork,” and “Doctor Communication” questions were reviewed for the intervention unit.

Data Analysis

The data for length of stay was visualized using Shewhart control charts with upper and lower control limits set at two standard deviations from the mean. Two members of the quality team analyzed the open-ended questions from the non-nursing staff survey and notes from the focus group using thematic analysis. Descriptive analyses were run for the survey data. Patient satisfaction scores are reported as the percent of respondents reporting top box and was visualized using run charts.

Results

Length of Stay

PDSA Cycle 1 started in March and the initial LOS decreased from an O/E of 1.75 (average 7.82 days; March 2022–February 2023) to 1.65 (average 7.88 days; April–May 2023). The second PDSA cycle started in May 2023 (average 7.73 days with an O/E 1.81). LOS had a mean of 7.77 days (O/E 1.77) for the entire study period (March 2023–Oct 2023). Overall, there was no significant decrease in length of stay (Figure 4).

The quality team also compared the LOS from the unit that implemented CTRs to the LOS on a similar unit at the same hospital that maintained the baseline state rounding method (Table 2).

Non-Nursing Staff Survey

Twenty-eight providers responded to the non-nursing staff survey: 31% resident physicians, 21% attending physicians, 18% case managers, 11% intern physicians, and 7% social workers. Most respondents (70%) participated in CTRs more than three times.

In the survey of non-nursing staff, 31% said that CTRs led to the initiation of the plan of care earlier in the day. Overall, 63% wanted to return to the prior rounding workflow, 26% wanted to continue with CTRs with changes, and 11% wanted to continue with CTRs.

Fifty-eight percent of respondents reported that the CTRs improved communication with nursing. They also reported improved communication with CM and SW, and that there were “less Epic chats.” One respondent reflected, “putting faces to otherwise names is more of a humane environment, I would assume it encourages participation.”

The main concerns from the attending physicians and residents were that there was insufficient time for teaching on these rounds. One respondent wrote, “Nice to have SW [social work] available to talk through extensive discharge planning when a patient is a difficult dispo[sition] or difficult hospitalization, it is helpful, but for some straightforward patient it hinders learning with the residents.” CM and SW felt that too much time was spent on education that was not relevant to their roles. One CM reported, “In my role, I am more concerned of when patients are medically ready for discharge. I felt time was being wasted for me because teaching medical information to residents regarding the cells and pathology is not going to help with discharging patients.”

Nursing Focus Group

Nine nurses attended the focus group in person with additional nurses joining via Zoom (the exact number of participants is difficult to count because some joined in groups). The nurses had a range of nursing experience: two RNs with 15 years, one RN with eight years, one RN with seven years, one RN with five years, two RNs with one to two years, and two new graduate nurses (one with two months and one with eight months).

Overall, RNs reported that communication with providers did not change with CTRs, and they continued to get information about the care plan from provider notes and through electronic communication (i.e., Epic chat). Nurses with more experience stated that they routinely reach out to providers in person or via Epic chat and did not feel like the CTRs improved communication. They felt rapport with providers was not built in a rounds setting but rather in other interactions. They also felt CTRs did not necessarily improve nurse sign-out shift to shift.

RN focus groups revealed that CTRs improved communication with CM and SW about discharge planning. One nurse reflected on an experience she had while floating to a different unit and how difficult it was to coordinate the discharge of a patient without knowing who the CM and SW were.

The majority felt the timing and the length of the rounds were challenging. RNs reported that CTRs interfered with morning tasks. One nurse reflected that CTRs were “helpful but at an inconvenient time.” Newer nurses found the CTRs made time management more difficult. One RN also felt that rounds were too long, and that providers could be more concise in their overview of the patient. RNs would rather discuss topics that pertain to nursing care and exclude topics unrelated to their care (e.g., differential diagnoses).

Patient Satisfaction

The HCAHPS scores for “Overall Hospital Rating,” “Unit Staff Worked Together,” and “Doctor Communication” are presented in Figure 5, Figure 6, and Figure 7. For all three metrics, there was a lot of variation noted in the score and data was limited due to the low number of surveys on the unit. Overall there was no significant trend over the study period.

Discussion

Despite reasons uncovered in the VSM exercise that indicated the need for change, the novel CTRs model was not successful. While the quality team noted an initial decrease in the O/E ratio for LOS after the first PDSA cycle, it was not sustained. This decrease in the O/E ratio was also observed in the control unit, indicating that the decrease was not due to the intervention and suggests another factor can be attributed to this observation. The initial time period for PDSA Cycle 1 was only two months long (March–April) and it’s possible that seasonality bias could be playing a role. The O/E ratio for LOS in April 2022, the baseline period, was similarly low (O/E=1.46), further supporting this theory. The novel rounding method was not favorable to care team providers, as evidenced by the findings of the team member survey and nursing focus groups. Additionally, there was no difference in patient satisfaction scores.

The findings on the impact of multidisciplinary rounding on patient outcomes is varied.4,8–10 While some studies show a decrease in LOS,4,10 other initiatives were not successful.8

One study demonstrated a slight difference in the observed LOS.4 Similar to the findings presented in this study which demonstrated an initial change in the O/E ratio, Patel et al.4 saw a decrease of five hours in the observed LOS; however, that was not sustained over time.4 Similarly, O’Mahony et al. demonstrated a slight decrease in the observed LOS of 0.5 days.10 While decreasing LOS by a few hours can improve throughput, it may not be substantial enough to justify the potential drawback of the intervention. Importantly, it was difficult to find literature that is more recent on interdisciplinary rounding, particularly at the bedside, given the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare practice. Blakeney et al. describe the need for published studies to detail rounding methodologies as done in this study to determine what components contribute to positive outcomes.11

The impact of rounding on resident education was one of the main barriers to the success of this initiative. Other studies have demonstrated that resident-centered multidisciplinary rounds enhanced resident education while improving quality outcomes.10 While there may be benefits to resident physicians, there are often trade-offs to other members of the care team. In our study, nurses reported that rounding conflicted with their morning tasks and made time management even more difficult. Given the busy schedules and disparate responsibilities and priorities of healthcare providers and staff, it is difficult to find suitable time slots for for all team members.3 The CTRs model presented in this study may be more suitable for a nonteaching/nonacademic hospital setting.

Based on the CTRs improvement project, it seems as though rounding with CM, SW, and nursing to plan for difficult patient discharges was seen favorably, and the amount of time that rounds took with team members who had different priorities was seen unfavorably. Despite ultimately returning to the baseline rounding state, this work is important to disseminate. The quality team presented a novel CTRs model that was evaluated by several methods. The project was discontinued because it was viewed unfavorably by staff, and did not show improvements in stated goals. The CTRs model may be more designed for a non-teaching hospital where there is less of a balance of education and care team member priorities.

There are several lessons learned that could benefit others. For true engagement and self-directed progress, the process must be perceived as valuable by all team members. When creating an interdisciplinary workflow, it is essential to evaluate its impact on each participant’s daily routine. The overall atmosphere and personal comfort also matter; many participants found busy hallways and large group presentations uncomfortable. Furthermore, when connecting workflows among interdisciplinary groups, a balance must be struck between efficiency and effective communication. While independent work may enhance efficiency, it often results in poor communication. Conversely, close collaboration can improve communication but tends to be time-consuming and inefficient. Processes that require significant encouragement from leadership are unlikely to succeed.

Limitations

One limitation of the current study was that LOS was measured by discharges from the intervention unit, which may not have solely included discharges from the Department of Medicine. However, there were few non-Medicine patients on this floor. A second limitation is that often patients with a long LOS elsewhere in the hospital are transferred to the medicine unit prior to discharge (after being downgraded from a surgical service or ICU) and thus are included in the medicine unit metrics.

Another limitation of this study was the inherent difficulty in quality studies to determine if the change in LOS after the first PDSA cycle was due to the intervention or external factors. This finding underscores the importance of continuing to track data over time. Importantly, the project was impacted by the start of a new academic year in July (during PDSA Cycle 2), which could have affected LOS. The study team also included the process measures of the electronic survey and the nursing focus group to better understand how the rounds were directly affecting the team.

The HCAHPS patient satisfaction scores were limited by a time lag in receiving real-time data for the surveys, as once they are received from the patient, it takes a while for results to be entered and available to the team. In addition, the response rate is low, which can affect summary data.

Conclusions

The quality team conducted and evaluated a multistep, interdisciplinary QI initiative to improve throughput using different methods. Despite these efforts, the team did not demonstrate improvement in throughput or communication. Additionally, CTRs were not popular among the majority of staff. The team used several methods to identify signs for suspending the project to ensure that resources are directed toward valuable activities.

Balancing the unique needs of each team member with the need to expedite communication is challenging in the inpatient medical service. Combining workflows expedites communication; however, it also leads to less efficient use of time. Future initiatives should use the lessons learned during this trial to strike the correct balance.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

The Quality Improvement Committee in the Department of Medicine at Mount Sinai Morningside and Mount Sinai West approved this initiative as a quality improvement project; thus, an institutional review board submission was not required.

About the Authors

Julie M. Pearson (julie.pearson@mssm.edu) is the director of Performance Improvement and Analytics in the Department of Medicine at Mount Sinai. She is a registered nurse and is certified in obstetric and neonatal quality and safety. She also earned her Master of Public Health from the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

Kim Keller is a transformational leader and experienced coach to executives, directors, and managers in strategic planning, Lean leadership, and utilization of daily management. She has led process improvement events with multidisciplinary teams across multiple industries, as well as developed curriculum and taught introductory and intermediate courses on change management, leadership, and improvement.

Emily Veldboom is a manager of patient care services at Mount Sinai Morningside hospital. She is a registered nurse who earned her Master of Science in nursing, along with her Master of Business Administration from Johns Hopkins University. She also completed the Academic-Practice Research Fellowship at Columbia University School of Nursing while working at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital.

Haley Waite is a former data analyst at The Mount Sinai Hospital. She earned her Master of Science in biomedical science from New York Medical College, as well as her Bachelor of Science in microbiology from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Faye Reiff-Pasarew is the deputy chief medical officer and associate chief of Hospital Medicine at Mount Sinai Morningside, where she works as an academic hospitalist. She trained at the University of California San Francisco for medical school, The Mount Sinai Hospital for her internal medicine residency, and completed the Clinical Quality Fellowship Program in Quality Improvement and Patient Safety with the Greater New York Hospital Association and United Hospital Fund. Her areas of focus include quality improvement, hospital operations, and the medical humanities.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)