Introduction

Problem Description

Physicians raised a concern to the Quality Department about patients who were diagnosed in the emergency department (ED) with a urinary tract infection (UTI) but who later were clinically reviewed and found to be without disease. These patients were often admitted and treated with potentially unnecessary antibiotics.

Available Knowledge

Urine cultures are intended to accurately identify if someone has enough bacteria in their urine to suggest they have a UTI and to identify the type of bacteria in the urine for appropriate antimicrobial therapy needed. Urine culture contamination prevents this purpose from being fulfilled by compromising the sample and affecting the culture growth and interpretation. The definition of a contaminated urine sample is any urine culture with mixed growth. Factors contributing to contamination include specimen handling, storage, and compromised collection techniques.

Delayed transfer from specimen collection cup to tubing with boric acid (known to slow organism growth), delayed transport of specimen to laboratory, and improper specimen storage all contribute to organism growth outside of the urinary tract, which can lead to misinterpretation of test results.

Midstream clean catch specimens are recommended to identify what organism is growing in the urinary tract. The first urine voided washes microorganisms and cellular debris out of the urethra. Bedpans and urinals should not be used for culture purposes as the vessels themselves are not sterile, it eliminates the midstream catch, and urine is often not collected directly after void.

Urine collection from a single catheter when there is high risk of contamination due to operator error is optimal1 compared to clean catch. Two-person urinary catheter insertion is recommended for both indwelling urinary catheter placement and straight catheter urine collection purposes.2 Both procedures are meant to be as sterile as possible to prevent transfer of organisms to the urinary tract while inserting the device.

Verbal patient education has been shown to be effective in reducing contamination3 and visual education has also been shown to separately reduce contamination.4

Previous literature has shown that urine culture contamination is directly related to adverse outcomes, including unnecessary antibiotic use,5 repeat culture costs,6 and unnecessary inpatient admissions.7 These outcomes can lead to additional cost to the patient and healthcare system while leading to additional poor outcomes.

Rationale

The Infection Prevention Department performed a current state assessment of 877 patients with contaminated urine cultures between August 2018 and January 2019. Of these patients, 79% were >65 years of age and 86% were female. The current state assessment showed that the average baseline urine culture contamination was 51% of all emergency department (ED) urine cultures. Urine culture contamination and resulting patient harm were investigated.

Specific Aims

Literature reviews show patient and staff education of a clean catch urine culture collection technique alone is not always effective at consistently reducing urine culture contamination.8–10 The intervention team hypothesized that an effective multifactorial method to reduce urine culture contamination would be a combination of staff education on appropriate midstream and straight catheter collection techniques, verbal and visual education for patients, and staff and physician identification of patients who would provide more accurate urine cultures via straight catheterization than clean catch.

The goal of this process improvement was to reduce unintended patient consequences of unnecessary admissions, unnecessary antibiotic treatment, and repeat urine cultures through reducing contaminated ED urine samples to ≤10% monthly contamination.

Key Project Terms and Definitions

-

Contaminated urine culture: any urine culture with mixed growth of more than two species of organisms identified.

-

The presence of Candida and common skin organisms were excluded from the contaminated culture definition, as their presence is deemed acceptable per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Urine collection sources of nephrostomy, urostomy, suprapubic catheter, and indwelling urinary catheters are known to be contaminated sources but were included in the contaminated culture count regardless.

-

-

Antibiotic recommended for UTI: >100,000 colonies of at least one identified bacteria genus in culture. For retrospective data analysis purposes only, symptoms were not considered.

-

If the urine culture had contamination but also >100,000 colonies per millileter (col/mL) predominate bacteria, antibiotic treatment was considered appropriate.

-

In these instances, antibiograms could generally be performed.

-

-

Unnecessary antibiotics: Patient prescribed antibiotics for a urine culture finalized with mixed growth of unknown genus and <100,000 colonies of bacteria, regardless of a main genus identified

- Antibiotics may have been given and appropriate for another reason. A repeat noncontaminated culture may have been performed which indicated appropriate antibiotics, but only the initial contaminated result was considered. Clinically, it may have been appropriate to treat the patient, especially if symptoms of infection were present.

Methodology

Context

The 250-bed teaching hospital specializing in geriatric and orthopedic acute care is part of a multihospital health system. The average ED patient visits are approximately 2,500 per month.

Interventions

1. Building the Team

The team of stakeholders started as two ED nurses, one infection preventionist (IP), one Quality nurse, and the Quality manager. The team was supported by the ED unit director and clinicians. As time passed, the stakeholders adjusted to one ED nurse, one ED physician’s assistant (PA), one IP, the Quality manager, and the Quality director. The aim was to get all team members together at least once per month.

An IP pulled monthly ED reports of urine cultures through a TheraDoc application. They reviewed the culture results and applied the project definition of contamination. They then reviewed contaminated cultures further via manual electronic health record review of ED notes to determine collection source documented; whether education was documented prior to clean catch collection; the cognitive, physical, and mobility documented descriptions of the patient; and the name of the staff member who collected the sample. Data analysis through chart review of patients with contaminated urine cultures suggested a multifactor cause for contaminated cultures. In February 2019, interventions began.

2. ED Staff Urinal and Bedpan Education

The baseline data was limited due to low staff documentation; however, it suggested that staff were using bedpans and urinals to collect urine culture samples. Both straight catheter and clean catch cultures were contaminated. Less than half of the patients providing clean catch samples had chart documentation indicating that staff provided education on technique prior to the sample. The first initiative was to reduce the collection of urine for culture through bedpans or urinals. Two ED nurse stakeholders provided peer-to-peer education as to why bedpans and urinals are not acceptable for culture collection.

The ED nurses created a presentation for the ED staff that consisted of

-

What’s currently happening

-

What not to do

-

Why you should not collect from bedpans, urinals, etc.

-

What to do: clean catch or straight catheter, and document

Discussions regarding teach-back patient education and quick transfer between collection cup and tubing with boric acid were determined not to be the primary focus at this time.

ED staff education began at the end of March 2019. Signs were hung in the ED supply room next to the bedpan and urinals that reiterated not to use these items for urine culture collection.

In August 2019, documentation of bedpan and urinal usage was slowing; however, stakeholders were still observing this process during rounds. In October 2019, staff flyers were made (Figure 1) and printed on bright yellow paper with the headline “Pee IS PRIORITY.” The first bullet point education was another reminder to not use bedpans or urinals for urine culture collection. The flyer used minimal wording and underlined key words. Two other initiatives and a reminder to document in the electronic health record how samples were obtained were on the flyer. These were placed around the ED halls, in the break room, and in staff bathrooms.

Between the end of November and early December 2019, the ED nurse stakeholder began providing face-to-face small huddles or individual feedback for staff who had ≥3 contaminated urine cultures the prior month. Feedback included documented details associated with the contamination, including bedpan or urinal usage, whether patient education was documented prior to clean catch samples, and any commendations for appropriate procedure documented. Personal conversations were supplemented with continued “Pee IS PRIORITY” flyers, weekly update emails to staff, and a section on urine culture contamination in the monthly ED newsletter. Discussions with staff during rounding suggested that email was not their preferred method of contact.

High census in winter 2019–2020 and the COVID-19 surge starting in March 2020 delayed further initiatives in this project. In July 2020, a “staff myths” survey was sent to the ED based on myths that were discovered during peer-to-peer rounding discussions. Questions included:

-

Do you use two staff members to assist with inserting a urinary catheter/straight catheter?

-

What are some barriers to using two staff members?

-

Do sterile straight catheter procedures cause UTIs?

-

Would visuals help to educate patients when there are language/learning barriers?

-

Select reasons why patients would not require education:

a. History of UTIs

b. History of pregnancy

c. Adult female

d. Patient frequently seen in ED

e. Patient states they have given urine samples before

f. None of the above

-

Do you change urinary catheter tubing before or after urine culture sample collection?

-

Do you obtain urine samples with a bedpan or urinal?

-

Do you have any concerns or questions regarding urine collection?

Of the 18 staff members who completed the survey, two stated that they still use bedpans or urinals. Staff education needed to be an ongoing initiative throughout the entire project.

3. Patient Education Initiative

One initiative consistently mentioned at each stakeholder meeting was patient education prior to obtaining clean catch samples; the education needed to include the cleaning of the peri area and midstream collection process. Feedback from ED staff indicated that patients may have verbalized that they understood the process but were still producing contaminated cultures. There was concern regarding language barriers. The intervention team decided that visual education for patients may be the best alternative.

A picture of the female clean catch urine collection process was reproduced from “Illustrations Reduce Contamination of Midstream Urine Samples in the Emergency Department”4 with arrows added to indicate the process flow (Figure 2). The pictures were printed on 4-by-5 paper to maintain patient privacy and were initially distributed in August 2019. There was an immediate decline in urine culture contamination starting in September 2019.

Although there was a decline in contamination, the number of handouts used was not documented and it was noted that stock did not need to be replenished. Post-intervention rounding and feedback from ED staff over the next few months suggested there was minimal staff buy-in with the visual education largely due to the cartoon depiction that staff did not find appropriate. As a result, Figure 2 visual education was pulled from the ED in November 2019 to better understand if other initiatives were the source of the contamination reduction.

Verbal patient education and advocating for patient teach-back continued to be requested from the ED staff. In November 2019, the ED staff nurse and ED PA on the intervention team discovered that patients who presented to registration triage in the ED were often given a urine specimen cup while in the waiting area to provide a sample, but were not given education on the collection process. This was immediately rectified and urine specimen cups were no longer distributed until education could be provided.

The “Pee IS PRIORITY” flyers and individual staff education with specific details for each staff member to improve continued. The staff myths survey results showed that 100% of the 18 staff members who completed the survey believed that visuals would help to educate patients where there are language/learning barriers, while 3 staff members believed there were reasons why you would not need to educate a patient on clean catch procedures again, including the patient stating they had given a urine sample before. This data was used to reinforce that education should be provided to every patient for every sample because there is no guarantee that they were educated appropriately in the past or that they remembered all required steps for clean catch.

One last visual education effort was made in May 2021 to provide drawings that were more accepted by staff. The simple drawings for both male and female clean catch available in both English and Spanish in Online Supplement Appendix A11 were used. The education was made available to the entire health system print shop in 4-by-6 handouts, full-page handouts, and 11-by-17 posters. Next planned steps were to order posters and place them in ED patient restrooms.

4. Advocating for Straight Catheter Collection

It was discussed during the team meeting in August 2019 that a small amount of bedpan and urinal collection was still occurring, straight catheter urine collection remained low, and documented clean catch samples were mostly older females needing assistance to ambulate. Straight catheterization was deemed more appropriate than clean catch procedure to produce an accurate urine culture when patients required mobility assistance, had physical barriers to follow each clean catch step, or had an altered mental status. The ED PA stakeholder was helpful in advocating for increased straight catheter orders by providers. She attended and presented at ED provider meetings from September through October 2019 and as needed.

The “Pee IS PRIORITY” flyers and the peer-to-peer staff education helped to advocate for straight catheter usage and dispel any myths. The staff myths survey resulted in the following:

-

16 of the 18 ED staff members who completed the survey stated that they did use two employees to insert a urinary catheter or straight catheter.

-

16 staff members gave reasons as to the barriers preventing the use of two employees for insertion: staff availability, department census, the belief that this would increase the risk of compromising the sterile field, and patient embarrassment.

-

ED staff, including nursing leadership, had mentioned several times during rounding that they were concerned an increase in straight catheterizations would cause UTIs. The myth survey only showed that 1 out of 18 ED staff still believed a sterile straight catheter procedure would cause a UTI.

Patients who were straight catheterized were resulting with contaminated urine cultures. ED competencies in October 2022 included completing online simulation training and hands-on sterile insertion technique with mannequins to improve straight catheter sterile technique. All newly hired ED staff received this same education. Although the team advocated for two-person urinary catheter insertion and straight catheter technique, this was not performed on a routine basis.

5. Additional Efforts

Throughout the project, the team mentioned to staff the need to handle and store the urine samples in such a way to prevent further contamination. If there appeared to be a delay in documentation between urine collection and being sent to the lab, this was also included in one-on-one education to ensure use of boric acid collection technique and to encourage timely delivery of culture to lab. This was mentioned, but was not a priority initiative.

In October 2020, a cake with a graph of contamination progress printed on the top was used to celebrate one year of decreased urine culture contamination rates. The purpose was to commend the staff on their work so far and maintain motivation to meet the goal of <10% sustained contamination.

Measures

Data measured included contamination percentage of all total urine cultures performed in the ED per month. Details of the contaminated cultures included collection source documentation, patient education prior to clean catch collection documentation, straight catheterization candidate factors, and the name of the staff member who collected the sample.

Straight catheterization, repeat urine cultures, antibiotics prescribed, and primary diagnosis of UTI with contaminated culture constituting as an unnecessary admission were also measured through patient coding.

Analysis

Quantitative data for contamination rate was calculated.

Supplemental data of documented urine source, staff member who obtained sample, documented patient education prior to clean catch, and staff survey results were all used as qualitative data to summarize the types of issues causing contamination.

Results

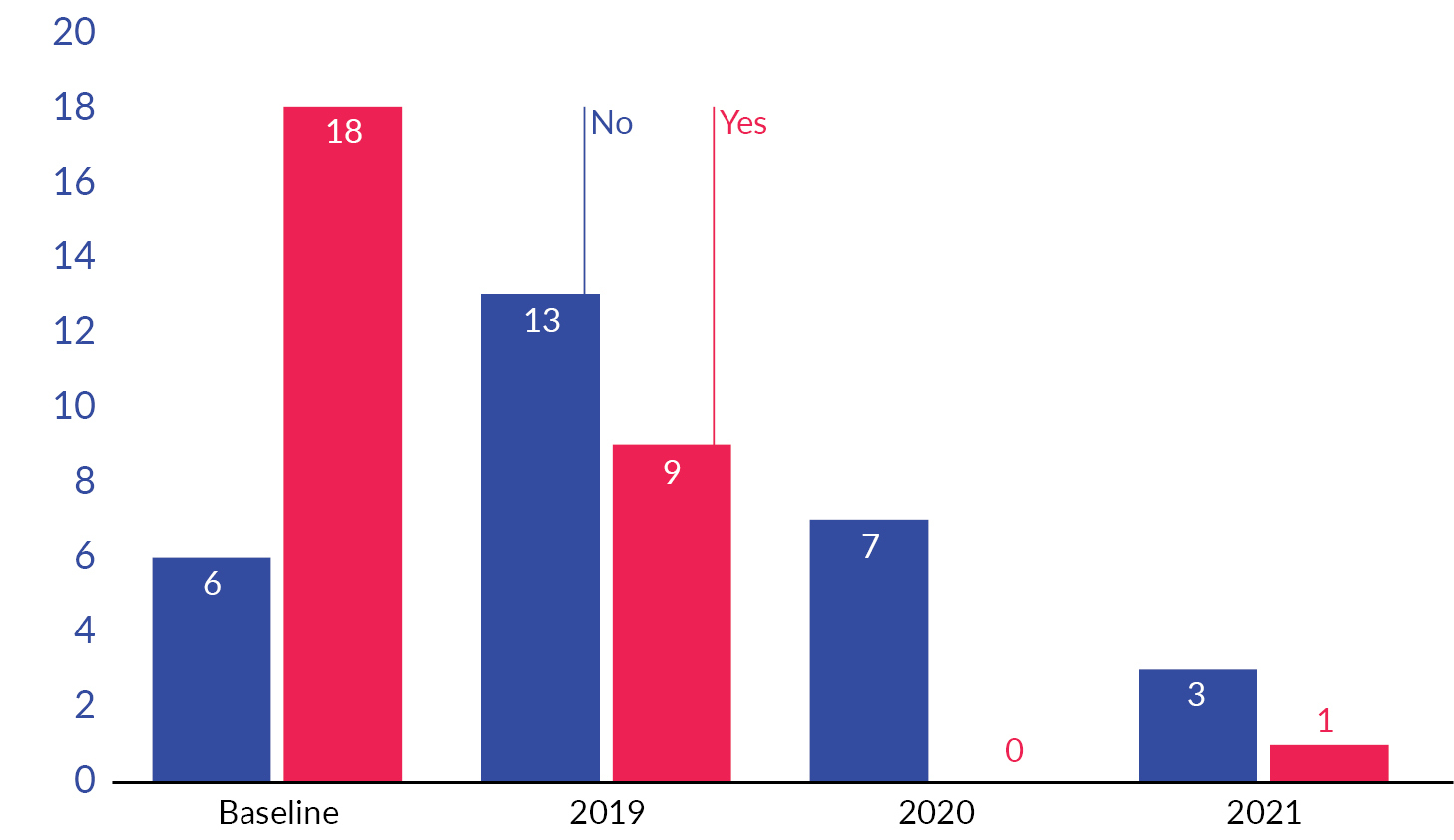

Stata 17 was used to perform statistical analyses at a 95% confidence interval. Urine contamination rates decreased from baseline average of 51% to six months of <10%, resulting in an 80% decrease (P<.001, CI 18.4-34). The highest contamination rate prior to interventions was 57.1% in December 2018 and decreased to the lowest contamination rate of 0.0% in May 2021 (Figure 3).

Due to the inability to manually pull data from all patient charts, a comparison of data was compiled between January 2019 within the baseline, January 2020, and January 2021 for approximate annual improvements (Figure 4). Overall urine culture contamination decreased each year. Documentation of urine source for collection increased each year. Bedpan or urinal documentation of use was only documented in January 2019. Zero documentation of bedpan or urinal use in 2020 or 2021 is not conclusive that usage of these items was eliminated, only that this procedure was not documented as performed. Straight catheter and documentation of urine source from high-risk contamination sources, such as nephrostomy, urostomy, suprapubic catheter, and indwelling urinary catheter, did increase from baseline to post-intervention. Patients with contaminated urine cultures in January 2019, before the interventions, required repeat urine culture within seven days of contaminated culture. This was not needed for patients in January 2020 and 2021. Patient education documentation did increase from baseline to post-intervention months.

Straight catheterization codes for all ED patients within the project timeframe of August 2018–May 2021 were reviewed and did show a trending increase (P=.003).

Secondary outcomes

Unnecessary Antibiotic Reduction

The admission codes of patients in the study were used to identify patients with contaminated urine cultures who were prescribed common antibiotics for patients with UTIs. Urine cultures were then reviewed to determine if the antibiotic was required or if the antibiotics were unnecessary. Figure 6 shows the decrease in unnecessary antibiotics for UTIs over time (P=.02).

Repeat Urine Culture Reduction

The admission codes of patients in the study were also compared with urine culture charge codes to identify patients who had a contaminated urine culture collected in the ED during the timeline and who had a repeat urine culture performed within seven days. Figure 6 shows the decrease in repeat urine culture ordering after contamination. This decrease is not statistically significant (P=.054).

Unnecessary Patient Admissions Reduction

There were 57 patients with contaminated urine cultures that were admitted or in observation and had a primary admit diagnosis of UTI. Out of those 57, 28 did not have a urine culture result indicating antibiotics were needed, meaning they were likely unnecessarily admitted. If the urine culture grew >100,000 bacteria or was not the reason for admission, any unnecessary admission was not attributed to the contaminated urine culture. Unnecessary admissions indicated by the orange columns in Figure 7 did show a declining trend between baseline and post-intervention patients (P=.001).

Discussion

The steep decline in culture contamination starting in September 2019 is correlated with repetitive messaging not to use bedpans or urinals for collection, signage in the supply room, patient visual education handouts, and the increase in physicians ordering straight catheter collection (P<.001). The final strides to attaining consistent levels of contamination <10% was a combined effort to continually educate staff on proper collection techniques, increased provider orders for straight catheterization, and improved verbal education techniques prior to patient clean catch. Frequent rounding, in-person discussions, and hands-on education are what drove the staff education.

The snapshot comparison between January 2019, 2020, and 2021 indicates possible secondary outcomes associated with urine contamination reduction. Documentation of urine source collection provided evidence that clean catch cultures were the main culprit for contamination. Although documentation of bedpan/urinal use decreased, rounding observations and answers to the staff myths survey indicated that this practice was not eliminated. Although documentation of straight catheter as the source of urine collection in January 2021 was zero, this was post-competency education and indicates that straight catheter source was decreasing in contamination. This snapshot comparison is the only quantitative data reflecting whether patient clean catch education increased throughout the project. The data reflects that documentation of patient education did increase following the intervention, but there is no evidence to validate that patient education increased from baseline and that documentation was the missing baseline factor.

The matching trending decline between urine culture contamination, unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, and unnecessary admissions of primary UTI diagnosis shows the correlation between contaminated urine cultures and two outcomes that could cause patient harm. Further analysis is needed to assess the correlation between urine culture contamination and repeat urine cultures within seven days.

Limitations

The knowledge that staff documentation was being audited did not appear to confound the results even though documentation of bedpan and urinal collection usage decreased, as did the contamination rate—showing that practice was changing, not just documentation. Frequent changes in ED staffing were a limitation to the stakeholder education abilities. Some staff working in the ED during the pandemic in 2020 were team members from other health system facilities that may not have been educated on proper urine collection techniques.

Readmission was a key focus for hospitals and that may have contributed to the success.

Laboratory urine culture reporting changes were made in October 2019 to report approximate col/ml of bacterial isolates for predominate pathogens. This change would not affect the project definition of contamination but could have contributed to more appropriately identifying patients requiring antibiotics for UTI. This may have skewed the results to appear that the project efforts decreased inappropriate antibiotic use more than the correlation should have reflected.

The Pharmacy Department initiated a quality improvement project in December 2019 comparing empiric antibiotic accuracy rates for UTIs based on resulted ED urine cultures and local antibiograms. This is not believed to have affected urine culture contamination but may have been a contributing factor to appropriate antibiotic improvement for UTIs.

Conclusion

Since adequate staff support of visual patient education was lacking until the end of the last month of the study, future investigations at other facilities would be intriguing to see if urine culture contamination would decrease faster with visual education that staff approved, combined with straight catheter competencies, increased straight catheter ordering, and elimination of bedpan and urinal collection all implemented together from the beginning. This project supports available literature that patient education on clean catch technique alone is not effective in decreasing urine contamination rates. Urine contamination decreased with a combination of staff education, patient education prior to clean catch, near elimination of bedpan or urinal collection, improvement in sterile straight catheter technique, and increased straight catheter ordering.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.