Introduction

Nurse burnout and poor well-being have direct implications for patient safety. First, burnout in nurses often manifests as impaired attention, which has been demonstrated to increase the likelihood of being involved in medical errors.1–4 For example, Melnyk and colleagues demonstrated a 26% to 71% higher likelihood of medical errors by healthcare providers reporting lower levels of physical and mental well-being.5 Second, burnout and poor well-being contribute to nurses leaving the workforce, which, in turn, reduces the number of nurses available to care for patients, reduces ongoing patient monitoring, and contributes to the loss of nursing expertise.4,6,7 Addressing the challenge of burnout and nurse well-being is a national priority.8,9

First, burnout in nurses often manifests as impaired attention, which has been demonstrated to increase the likelihood of being involved in medical errors…

Second, burnout and poor well-being contribute to nurses leaving the workforce, which, in turn, reduces the number of nurses available to care for patients…

Burnout refers to the emotional depletion and loss of motivation from prolonged exposure to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job.10 Burnout has been described as high levels of emotional exhaustion and low sense of accomplishment and motivation within the workplace.11,12 Nurse burnout rose during the COVID-19 pandemic, with one study finding that over half of the nurses surveyed experienced burnout.13 While the recent data on nurse burnout and well-being are staggering, these issues have affected nurses for decades.14 Stress and burnout have been widely studied and identified as occupational hazards and key factors influencing nursing quality of life, quality of care, and patient outcomes.14–17 Studies conducted between 2003 and 2021 identified workload demands, work environment, and reduced resources as contributors to stress, impaired physical and mental well-being, and burnout among nurses.11,16–27

With the COVID-19 pandemic bringing greater attention to nurse burnout, there has been an increased effort to understand prevalence and key contributing factors to burnout. Several surveys have been conducted to determine the impact of the pandemic on nurses’ well-being and to identify specific stressors associated with intent to leave.28–33 In the second year of an annual COVID-19 survey conducted by the American Nurses Foundation in 2022, over 12,000 nurses were surveyed to gain additional insight on the effect of the pandemic on nurses, staffing, and intent to leave the profession. Findings included a statistically significant relationship between age and emotional health of nurses; an increase in the percentage of nurses intending to leave their position; and increases in staff shortages, incivility, and bullying.29

In response to the high levels of nurse burnout and well-being challenges, some healthcare facilities have launched programs focused on improving nurse well-being. Compared to well-being initiatives focused on physicians, especially trainees, nurse well-being programs are quite new and little research has been done to evaluate whether these programs are addressing nurses’ concerns.34–39 Having effective well-being programs in place to support nurses is critical for nurse safety, retention, and patient safety.

In this qualitative study we sought to identify whether nurses’ concerns about burnout and well-being are aligned with the focus of healthcare system well-being programs intended for nurses. We focused on sourcing nurse concerns from social media posts. Social media often provides an anonymous platform for expressing concerns, which may potentially result in more open and honest sharing compared to organizational surveys and interviews that can be perceived as not being anonymous.40,41 Identifying misalignments between nurse well-being concerns and the focus of current well-being programs offers the opportunity to optimize these programs to provide better support to the nurse workforce. Based on our analysis, we provide recommendations for improving methods for sourcing information on nurse concerns and for improving current well-being programs.

Methods

Social Media Analysis

We analyzed social media content from a nurse-specific Reddit forum. Reddit forums are structured with an initial post, which is a user leaving a comment/question, and then subsequent comments/questions are presented in response to the initial post. Together, the post and resulting comments/questions make up a thread.

We first retrieved all publicly available did not contain language relevant to any of the eight domains and were removed from analysis, resulting in 27 threads included for analysis. From these 27 threads, the five highest-rated, first-level comments from self-reported registered nurses were extracted from each post, yielding 135 comments for review. These comments were also reviewed for relevance based on the Swarbrick model. Fifteen comments did not contain language relevant to any of the eight domains and were removed, resulting in 120 comments for qualitative analysis. Figure 1 summarizes the data selection process.

Using the topics and themes in Table 1, as well as subthemes (shown in Table 2) the 120 social media comments were then manually reviewed and dually coded by a nurse and human factors expert, with discrepancies reconciled through group discussion. Each comment was coded into a single primary topic, theme, and subtheme to best reflect the nature of the comment. The topics, themes, and subthemes were based primarily on Swarbrick’s wellness model, as well as healthy work environments (HWEs), and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s (NASEM) systems model of burnout and well-being.42–44 Table 1 shows the complete list of topics and themes used to code the social media and interview data, with details of the interview method presented below. Note: Some topics, themes, and subthemes were only relevant to the social media analysis, while others were only relevant to the interviews.

Semistructured Interviews

Semistructured interviews were conducted with nine leaders of nurse well-being programs from seven healthcare systems with varying geographic locations. The goal was to understand their perception of the factors contributing to poor nurse well-being, of initiatives to address these contributing factors, and of metrics used to evaluate their own well-being initiatives. A convenience sample of healthcare leaders involved in nurse well-being initiatives was recruited. Interviews were led by clinical and human factors experts and conducted over two months, with each interview lasting approximately 30 minutes. All participants provided verbal consent before starting the interview. Interviews were conducted via video teleconference using a moderator guide. After consent from participants, interviews were recorded and electronically transcribed. Participants were compensated with a $25 Amazon gift card. This study was approved by MedStar Health Research Institute Institutional Review Board.

Participants’ responses were segmented into discrete statements. A grounded theory approach was used to analyze interview data.45 The same codes iteratively developed for the social media data were also applied to the interview data. Participants’ responses were mapped to the topics and themes by one researcher, and independently confirmed by a second researcher. Discrepancies were resolved through group discussion. Descriptions, examples, and representative quotes were used to provide insight and support for identified topics and themes.

Results

Social Media Results

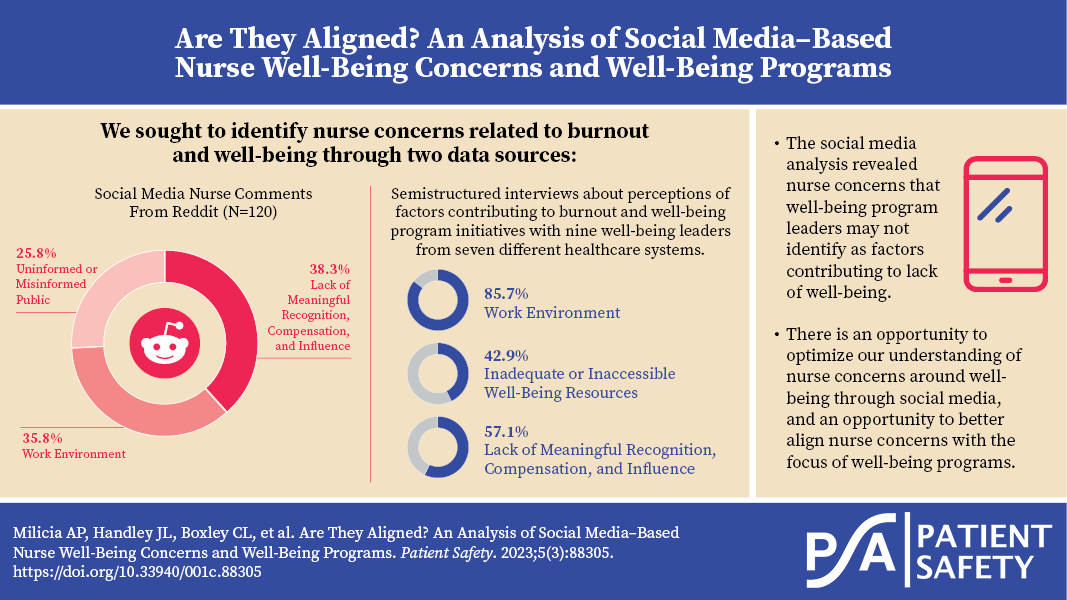

Of the 120 comments analyzed, the most frequent topic was Lack of Meaningful Recognition, Compensation, and Influence (n=46 of 120, 38.3%), followed by Work Environment (n=43, 35.8%) and Uninformed or Misinformed Public (n=31, 25.8%). There were no comments related to the topic of Inadequate or Inaccessible Well-Being Resources. Frequency counts and percentages of the topics, themes, and subthemes are displayed in Table 2, below.

The comments related to Lack of Meaningful Recognition, Compensation, and Influence included the themes of Constrained Professional Agency and Compensation. There were no comments related to the theme of Lack of Opportunity to Influence Organizational Decisions. Constrained Professional Agency accounted for 32 comments (of 46, 69.6%) (the most frequent theme across all topics and themes), and the most frequent subtheme was health system or macrosystem (i.e., federal, state, or funders) policies or regulations that limit nurses’ ability to respond effectively to patient care needs (n=22 of 32, 68.8%). Compensation accounted for 14 comments (of 46, 30.4%) and comments were almost evenly distributed between the three subthemes of disparity between staff nurses and travel nurses, disparity between salaries of nurses and health system executives, and insensitive/disrespectful organizational communications regarding healthcare worker compensation (n=5 of 14, 35.7%; n=5, 35.7%, and n=4, 28.6%, respectively).

The comments related to Work Environment included themes of Inadequate Nurse Staffing, Violence Against Nursing, and the Emotional Burden of Nursing, with the two most prominent being Inadequate Nurse Staffing and Violence Against Nursing (both accounting for 16 of 43 Work Environment comments, 37.2%). There were no comments related to the theme of Unusable or Burdensome Technology. Within the theme of Inadequate Nurse Staffing, most comments were related to ineffective organizational strategies to retain (original staff/pre-pandemic staff) nurses (n=9 of 16, 56.3%). Subthemes related to Violence Against Nursing were roughly evenly split between physical violence (n=6 of 16, 37.5%), nurse-to-nurse/nurse-to-student incivility (n=5, 31.3%), and culturally motivated violence (n=5, 31.3%). Nearly three quarters of the comments related to Emotional Burden of Nursing included the subtheme of emotional toll of being with patients as they die—often the nurse was the only one with the patient, as the family may not have been permitted to be physically present (n=8 of 11, 72.7%).

The comments related to Uninformed or Misinformed Public were coded as the third most frequent topic, accounting for roughly a quarter of all comments (31 of 120, 25.8%), and included themes of Uninformed Knowledge of Healthcare Operations/Personnel (n=17 of 31, 54.8%) and COVID-19 Misinformation (n=14, 45.2%). All subthemes related to both themes were roughly evenly distributed.

Semistructured Interview Results

The interviews of the nine nurse well-being leaders from seven healthcare systems revealed information about the factors contributing to the lack of well-being, the current well-being initiatives that have been put in place to address these contributing factors, and metrics for measuring improvements in well-being. Results of the interview data are discussed at the organizational level with a sample size of seven.

Factors Contributing to the Lack of Nurse Well-Being

Of the seven healthcare systems interviewed, the most common topics that emerged from asking about the factors contributing to the lack of nurse well-being were the Work Environment (n=6 of 7, 85.7%), followed by Lack of Meaningful Recognition, Compensation, and Influence (n=4, 57.1%), and Inadequate or Inaccessible Well-Being Resources (n=3, 42.9%). There were no comments related to the topic of Uninformed or Misinformed Public. Table 3 summarizes these results.

Of the six healthcare systems that noted the Work Environment topic as a contributing factor to the lack of nurse well-being, Inadequate Nurse Staffing (n=6 of 6, 100%) was noted by all systems. Other Work Environment themes that impacted lack of nurse well-being included the Emotional Burden of Nursing (n=4, 66.7%), Unusable or Burdensome Technology (n=2, 33.3%), and Violence Against Nursing (n=1, 16.7%).

Of the four healthcare systems that noted Lack of Meaningful Recognition, Compensation, and Influence, all systems noted the Lack of Opportunity to Influence Organizational Decisions (n=4 of 4, 100%). Compensation was mentioned by three quarters of the well-being leaders interviewed (n=3 of 4, 75%) and Constrained Professional Agency was noted by two healthcare systems (n=2, 50%).

Of the three healthcare systems that noted Inadequate or Inaccessible Well-Being Resources, two of the systems stated that nurses felt like they did not have Access to Resources to Maintain/Promote Well-Being (n=2 of 3, 66.7%). Inadequate Employee Assistance Program (EAP) and Benefits and Lack of Well-Being Training and Education were both noted by a single healthcare system (n=1 of 3, 33.3%).

Current Well-Being Initiatives

To address the Work Environment as a topic contributing to the lack of nurse well-being, healthcare systems have implemented several well-being initiatives, including creating a physical space for relaxation before, during, or after shifts (n=2 of 7, 28.6%); changing policy (n=2, 28.6%); changing working processes (n=1, 14.3%); and optimizing technology (n=1, 14.3%). Table 4 shows a summary of current nurse well-being initiatives offered by the healthcare systems interviewed. One policy change example is a healthcare system updated their policy so that staff could safely take a power nap during their 30-minute unpaid lunch break. Previously, nurses would be terminated if they slept anytime during their shift. Another healthcare system described a pilot program in their emergency department where they changed a work process allowing nurses to request a 5-to-10-minute well-being break on a communication application on their phone during their shift. Finally, one healthcare system is making improvements to “minimize nursing documents and function so they have time for clinical thinking” (optimizing technology).

To address the Lack of Meaningful Recognition, Compensation, and Influence as a topic contributing to the lack of nurse well-being, healthcare systems interviewed described two programs. Some healthcare systems (n=4 of 7, 57.1%) described financially incentivizing well-being, including paying cash rewards (up to $1,000 per year) for utilizing a well-being application that tracks movement (specifically steps taken) and other healthy habits, and paying employees to take educational programs that promote well-being. Another example of a healthcare facility financially incentivizing well-being includes linking participation in well-being activities to medical insurance premiums. One participant noted, “Connection with the medical premiums and seeing how much money that you can save has been kind of a no-brainer for all of us that are on the medical insurance.” Two healthcare systems (28.6%) described gratitude programs. An example of a gratitude program is the “Thank You Project,” an opportunity for someone who’s received care at the hospital to recognize anyone who was part of their patient experience.

Nurse burnout and lack of well-being not only impact nurses, but also have serious patient safety consequences and are associated with increased likelihood of medical error and reductions in workforce which result in fewer nurses available to deliver care.

To address Inadequate or Inaccessible Well-Being Resources, healthcare systems have completed a variety of things. Over half of the healthcare systems interviewed (n=4 of 7, 57.1%) have implemented peer support and mentoring programs, including initiatives such as Stress First Aid and Care for the Caregiver. Many healthcare systems (n=4, 57.1%) have held well-being events, such as yoga classes or pet therapy, and provided education, such as healing touch classes. Healthcare systems have started to share more well-being resources and made them more accessible (n=3, 42.9%), improved their EAP and benefits (n=3, 42.9%), and created and shared well-being content during new employee orientation (n=3, 42.9%). Healthcare systems have also hired well-being leaders to help with well-being initiatives (n=3, 42.9%).

Metrics of Well-Being Initiatives

Metrics used to measure nurse well-being at healthcare systems varied. Surveys were the most common method to measure nurse well-being (n=4 of 7, 57.1%), followed by utilization rates of programs (n=3, 42.9%), anecdotes (n=3, 42.9%), and retention rates (n=2, 28.6%). Interestingly, one healthcare system (14.3%) was utilizing medical claims as a metric of nurse well-being.

Discussion

Nurse burnout and lack of well-being not only impact nurses, but also have serious patient safety consequences and are associated with increased likelihood of medical error and reductions in workforce which result in fewer nurses available to deliver care.1–3,6,7,46 Ensuring that appropriate well-being programs are in place to support nurses is critical to patient safety.47,48 Our unique analysis focused on analyzing social media data related to burnout and well-being to identify nurse concerns and interviewing well-being leaders to understand the factors contributing to lack of well-being, current well-being initiatives, and metrics associated with their programs.

Comparing the social media–based concerns to the topics that emerged from interviews focused on factors contributing to the lack of well-being and current initiatives provides one perspective on whether the well-being programs are meeting the needs of nurses. Table 5 shows a direct comparison of the topics and themes identified from the social media analysis and interviews. Identifying misalignments between the social media analysis and well-being leader interviews may present opportunities to improve well-being programs.

Based on the social media analysis, the most prominent topic was Lack of Meaningful Recognition, Compensation, and Influence followed by Work Environment, and finally Uninformed or Misinformed Public. From the interviews, at the topic level the most prominent was Work Environment, followed by Lack of Meaningful Recognition, Compensation, and Influence, and then Inadequate or Inaccessible Well-Being Resources. Interestingly, the topic of Uninformed or Misinformed Public which surfaced from the social media analysis was not mentioned by any of the well-being leaders. On the contrary, the topic of Inadequate or Inaccessible Resources was a contributing factor topic for well-being leaders but was not mentioned in the social media analysis.

While the topics of Lack of Meaningful Recognition, Compensation, and Influence and Work Environment were identified through social media analysis and interviews, there were some differences in the specific themes. The social media analysis did not reveal any explicit comments related to the theme of Lack of Opportunity to Influence Organizational Decisions under the topic Lack of Meaningful Recognition, Compensation, and Influence. In addition, the social media analysis did not reveal any comments related to Unusable or Burdensome Technology under the theme of Work Environment. This is surprising given both themes have been discussed extensively in the literature and other forums.49–52

In the social media analysis, there is not a substantial difference in frequency of comments related to the topics of Lack of Meaningful Recognition, Compensation, and Influence and the topic of Work Environment; however, many comments fell under the subtheme of health system or macrosystem policies or regulations that limit nurses’ ability to respond effectively to patient care needs. This suggests that addressing this subtheme will be important for addressing overall nurse burnout and lack of well-being. This subtheme will be challenging to address at a health system or national level given the diversity of stakeholders and the complexity of the issues impacting these policies and recommendations.

The interview data revealed some interesting well-being initiatives addressing some concerns expressed in the social media analysis. There is an opportunity to further study the impact of these initiatives and to share the most effective initiatives nationally. The biggest gap noted in the well-being initiatives described is addressing the topic of Uninformed or Misinformed Public.

The interview data surrounding metrics of well-being initiatives highlight the opportunity to improve our measurement of these initiatives. Survey-based instruments were the most common and while survey data are important, additional methods are needed to better quantify the potential impact of well-being programs. This is a key area for future research and development.

Fundamental to addressing nurse burnout and well-being is understanding the factors that are driving these issues. While many facilities conduct surveys to understand factors contributing to burnout and lack of well-being, surveys alone may not capture all the key concerns.

Recommendations for Healthcare Facilities

Fully addressing nurse burnout and well-being will require federal, state, and institutional changes to certain policies, compensation models, and numerous other factors. In addition to those efforts, our social media analysis and interviews lay the foundation for several recommendations healthcare facilities should consider in their immediate efforts to address nurse burnout and well-being. These recommendations include:

Use a multipronged approach to understand nurse concerns: Fundamental to addressing nurse burnout and well-being is understanding the factors that are driving these issues. While many facilities conduct surveys to understand factors contributing to burnout and lack of well-being, surveys alone may not capture all the key concerns. Further, there can be tremendous variation in the factors that contribute to burnout from facility to facility and even department to department. These factors are difficult to capture by surveys alone. In addition to surveys, healthcare facilities should interview nurses; use different polling platforms, including social media; and conduct observations to identify what tasks and interactions may be contributing to burnout.

Embrace positive deviance: Positive deviance is focused on identifying groups or individuals with better outcomes than their peers, studying their behaviors, and then using this knowledge to inform the practices of others.53 Many healthcare facilities focus on those individuals with high levels of burnout. While this is important, there can also be lessons learned from understanding what factors contribute to low levels of burnout. Observing, interviewing, and surveying those with low levels of burnout may surface key insights that can be brought to those with high levels of burnout.

Develop ways to address nurse concerns around constrained professional agency: The social media analysis revealed that Constrained Professional Agency was one of the most frequently discussed issues. Constrained professional agency is the hindrance of one’s ability to influence and make choices in a way that affects their personal identity, career, and practices, including lack of flexibility or autonomy from a systemic level.54 Facilities should focus on addressing these issues at a local level. One approach is to conduct focus groups with nurses to learn how they might be better supported on this issue.

Develop strategies to discuss issues around uninformed or misinformed public with nurses: This issue surfaced in the social media analysis and was not described by any of the well-being leaders, suggesting there may be a significant gap. Facilities should develop strategies for discussing this issue with their nurses, acknowledging that this is a known issue and developing interventions to relieve the stress associated with this problem.

Improve well-being program measurement efforts: To develop a successful well-being program, frequent measurement of program goals is important. Facilities should develop data points aimed at measuring burnout, well-being, and the impact of programs. These can be operational metrics (for example, number of surveys completed) though we recommend that at a minimum they include some outcome metrics, such as any improvement in well-being and whether implemented programs are having an impact. Measurements taken at regular intervals with the least amount of burden on staff are important. Consistency in measurement is also important for benchmarking and understanding well-being in context—aligning measurement efforts with existing standards will speed implementation and allow for effective comparisons within and across organizations.

Engage other well-being leaders to share what is and isn’t working: The interviews we conducted served to identify several different well-being initiatives. There is an opportunity to increase knowledge sharing across organizations and given the common ground of wanting to improve nurse well-being and patient safety, there should be little hesitation to sharing what works. Current collaborative efforts to share in both well-being measurement and knowledge sharing around programs and solutions include the Healthcare Professional Well-being Academic Consortium, which has recently expanded its nurse well-being survey content to develop national benchmarks for nurse well-being.55

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. Our social media analysis was based on data from a Reddit forum focused on nurse-related topics. However, we cannot verify the identity of social media posters to determine if they are, in fact, nurses that are engaging in this social media platform. We also have no way to verify the accuracy of the questions/comments that were analyzed. We sampled a small segment of the social media content, and the coding of this content may not accurately reflect the entire dataset. As with all interviews, we captured the experiences of those individuals interviewed; however, we were not able to verify the accuracy of these experiences. Additionally, we utilized a convenience sample of nurse leaders from a small subset of healthcare facilities in the United States and the results may not be generalizable to all healthcare facilities.

Conclusion

Nurse burnout and lack of well-being have clear implications for patient safety, and addressing the factors contributing to burnout is a national priority. Nurse concerns about burnout and well-being may not be fully addressed by current well-being programs. There is an opportunity to optimize current well-being programs by ensuring alignment between nurse concerns and well-being program initiatives and by improving measurement of the effectiveness of well-being programs.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests.

About the Authors

Arianna P. Milicia (arianna.p.milicia@medstar.net) is a senior research analyst at the MedStar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare.

Jessica L. Handley is the associate director of operations at the MedStar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare.

Christian L. Boxley is a data analyst at the MedStar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare.

Deanna-Nicole C. Busog is a research analyst at the MedStar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare.

Seth Krevat is the senior medical director at the MedStar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare and an assistant professor at Georgetown University School of Medicine.

Nate Apathy is a research scientist at the MedStar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare.

Daniel Marchalik is the executive director of the MedStar Health Center for Wellbeing and an associate professor at Georgetown University School of Medicine.

Raj M. Ratwani is the director of the MedStar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare, vice president of scientific affairs at the MedStar Health Research Institute, and an associate professor at Georgetown University School of Medicine.

Ella S. Franklin is the senior director of Nursing Research and Systems Safety Science at the MedStar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare.